Landscapes and Videotapes by Emmalea Russo

This essay was probably my favorite story Burnaway published this year, for a number of reasons. When people talk about art critics and art criticism, the stereotype is stuffy, white, rich, disconnected from reality. What struck me so much about Emmalea Russo’s “Landscapes and Videotapes” was how it directly connected her experience with art (sex, lies, and videotapes) to the land on which she lived and where the art was created, and the moments in life that flowed around them. Art does not exist in a vacuum, nor should we be afraid to talk about art as it relates to a collection of photographs from an old lover, or the heat of longing.

— Jasmine Amussen, Editor

Paradise and Catastrophe: FloodZone and Anastasia Samoylova’s Miami by E.C. Flamming

As many of us put our vacations on hold this year, Florida was on my mind. As one of the first states to reopen, it garnered media attention as its number of cases surged. At Burnaway, our attention turned to the vacation-destination state through Mood Ring projects and editorial themes. Published as part of our series on Waterways / Water Wars, Flamming’s essay introduced me to the work of Anastasia Samoylova, whose photographs document the aftermath of hurricane flooding and destruction in Miami. The essay grapples with the strange beauty of catastrophe in paradise and likens their documentation to a visual eulogy for the land and people who inhabit these flood zones.

— Emily Llamazales, Programs Assistant

Courtesy Institute 193, Lexington. © Guy Mendes, 2019.

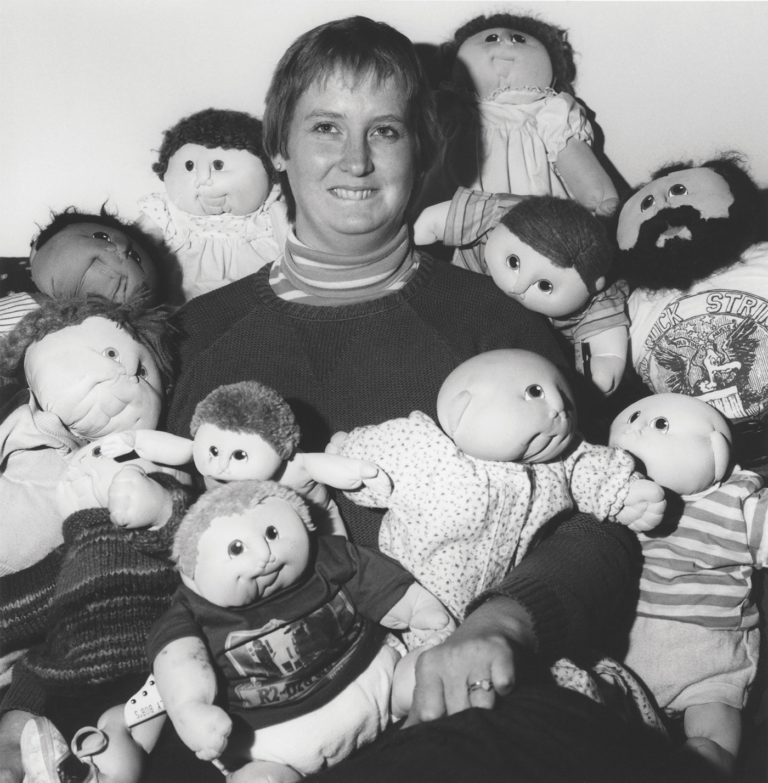

The Truth About Dolls by Margaret Jane Joffrion

It would be a stretch to call Margaret Jane Joffrion’s essay about a visit to Louisville’s KMAC Museum an exhibition review—sure, she describes and analyzes works of art from two shows, Where Paradise Lay and Julie Baldyga’s Heavenly People, but the central animating force of the story is her own voice, that most cherished possession of every writer. Margaret Jane isn’t afraid to speculate wildly or boldly venture off into lyricism: among other stops along the way, this essay includes an imaginary quote by Bruce Springsteen, a conversation between the author and stuffed dolls, and various theories about childhood and heaven. But somehow, word by word, she threads these wandering passages into a coherent form that is exquisitely idiosyncratic and tender. Perhaps she offers a clue for other writers who would follow in her way: “Fill the pail with observation, and empty it to water the garden.”

— Logan Lockner, Editor-in-Chief

Mississippi v. Tennessee by Cecil Howell

A landscape architect by trade, Cecil is not someone who would traditionally be viewed as an art critic, but her work immediately appeared so relevant to the magazine’s thematic investigations of Waterways / Water Wars this year. The images in Cecil’s project Mississippi v. Tennessee—which visually translates a legal dispute over water between the two states—are so rich and powerful that we decided to divide them into two portions so as to not overwhelm the reader with their terrible beauty and details of a developing environmental catastrophe.

— JA

My Island by Erin Jane Nelson

In March the Nintendo Switch was sold out everywhere within a 500 mile radius from my house, despite the console having been on the market since March of 2017. The surge in sales caused by the imminent lockdown and the craze for Animal Crossing: New Horizons was projected all over the internet. I begged for someone, anyone, to share their old copy of Animal Crossing: Wild World for Nintendo DS with me so I could plunge back into the game of my childhood. Often enough, the Georgia coast and its barrier islands seem like estranged extensions of my home state, much like my memory of my village in Animal Crossing. What “My Island” brings to the forefront is the paradox between extraction and destruction brought onto these small lands in the wave of settler colonialism set against the immense natural beauty of wild horses standing on an empty beach against a backdrop of Spanish moss. There is a strange beauty locked within a game’s imaginary world, as there is in sites whose histories are fraught with grief and despair alongside such natural beauty. “My Island” goes on to connect the mental struggles of pandemic isolation to that imagined feeling of being stuck on a deserted island, comforting me in knowing I was not alone in this strange new world.

— EL

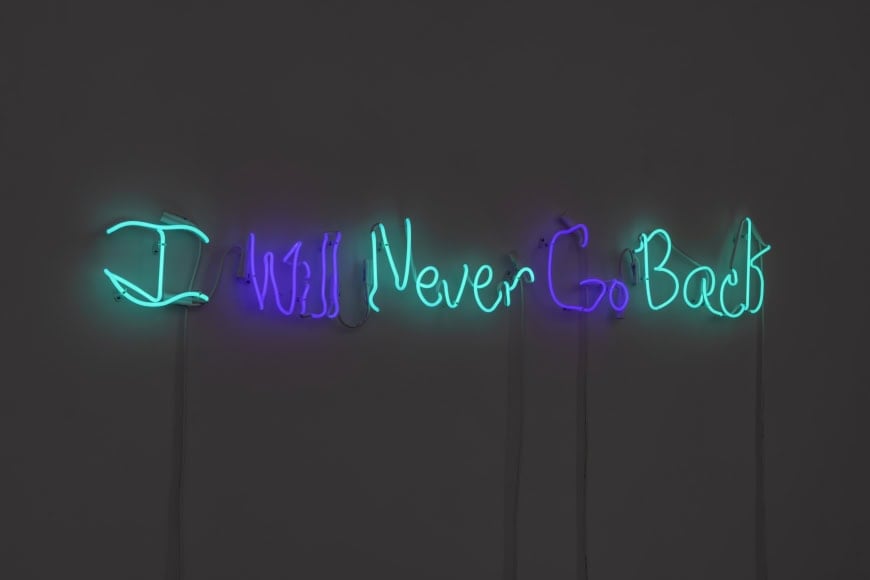

I Will Always Love You by Ronicka McClain

When I was a kid growing up in East Tennessee in the 90s, there were a few years when my family had season passes to Dollywood, visiting the theme park up to a dozen times a year to ride roller coasters, eat fried food, and listen to gospel music played through speakers disguised as rocks and boulders. One of the reasons I love Ronicka McClain’s essay about a trip to Dollywood is that it brings together this familiar, opulently kitschy landscape from my childhood with the sort of profound moments of personal reflection and cultural identification that have shaped my life as a young adult grappling with queerness. Without lapsing into reductive clichés, Ronicka shows how moments of identifying with a celebrity or diva can alter the lives of queer people as individuals and impact queer culture more broadly, while also deftly considering how race and gender play into this process of self-making.

— LL

“An open casket for a puerto rican obituary” by Raquel Salas Rivera

The idea for Burnaway’s tiny book of poetry Nights of Measure came around in the early days of pandemic. Everything was closed, and it felt flippant and wrong to do something perfunctory like review a show that was indefinitely shuttered. I met Raquel on the tail end of my residency at MacDowell at the very beginning of 2020. I loved how quick to laugh he was, and how he bravely agreed to traipse through the New Hampshire woods to find a fabled mystery shrine with me. When I asked him to submit a poem for the chapbook, I was thinking of the poem he read with me on my last night at MacDowell. Instead, he turned in this poem, which was so arresting, so shocking, that I had to stop reading at several moments to cry, to laugh, to lie down, trying to hold on to who I was amid a time that was so devastating, life-changing, and—I hope, ultimately—revolutionary.

— JA

Ghost in the Machine: Jacolby Satterwhite at Mitchell-Innes & Nash by Madeleine Seidel

Already familiar with the scope of Jacolby’s Satterwhite’s work, I was looking forward to reading Seidel’s review of his most recent exhibition. As an artist, knowing where to look for inspiration can be a huge stumbling block, and finding something inward or familial is often my first step toward unlocking new ideas. What fascinates me about Satterwhite’s work is that he pulls from a seemingly endless stream of music and ideas created by his late mother. There is a dream-like enchantment in his videos, which combine her folk-like drawings with motifs and references to art history. Seidel sheds a light onto this unresolved feeling, bringing the ideas of hauntology and simulacra to the table for our consideration as we move through Satterwhite’s work.

— EL

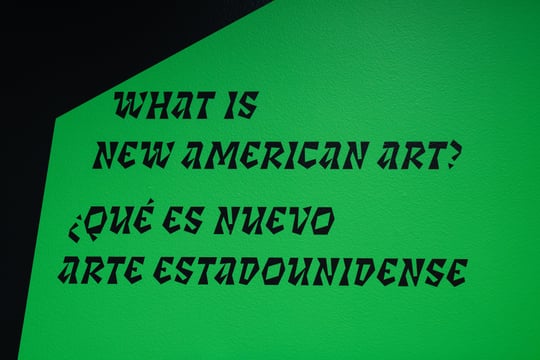

Mood Ring: María Korol by María Korol

The magazine’s artist column Mood Ring is consistently one of my favorite features to work on, but the edition by Atlanta-based artist María Korol stands out to me as a particularly rich and compelling installment from the past year. I love how inviting artists to contribute to the magazine gives an opportunity to witness otherwise obscured parts of their practices and creative lives, such as María’s poetry, published here in Spanish and English. This Mood Ring project also served as something of a preview for Nightwork, María’s Edge Award exhibition at Swan Coach House Gallery, which opened in October after being postponed due to the pandemic. Including some of the drawings from her Mood Ring alongside ceramics and a stop-motion animation, Nightwork was a welcome return to seeing art in person and appreciating its subtleties, humor, and technical delights.

— LL

You’re Obviously in the Wrong Place by Jasmine Amussen

Perhaps it is cheating to pick one of your own essays as one of your favorite stories of the year, but I’m doing it. This is the last piece I wrote for the magazine I wrote before I left for my residency in January, which more or less corresponded with the period when the virus was something we knew about but wasn’t yet a pandemic. The themes of this piece—fantasy, impotent rage, desire, exhaustion, cynicism—feel eerily prescient for the surreal year it preceded. Now we are all too familiar with the overwhelming desire to escape incredible violence—real, psychic, emotional—into a world of beauty and fantasy, a place where no one is hurt and everyone can be a princess. This essay is also very personal to me as a critic: it’s about things I find disgusting, and that drive me into a rage—things that seem so silly now, in light of whatever all of this is. But I hope there will be a time where I can enjoy pretty clothes and bad conceptual art again, when these are the most serious things I spend my day thinking about.

— JA

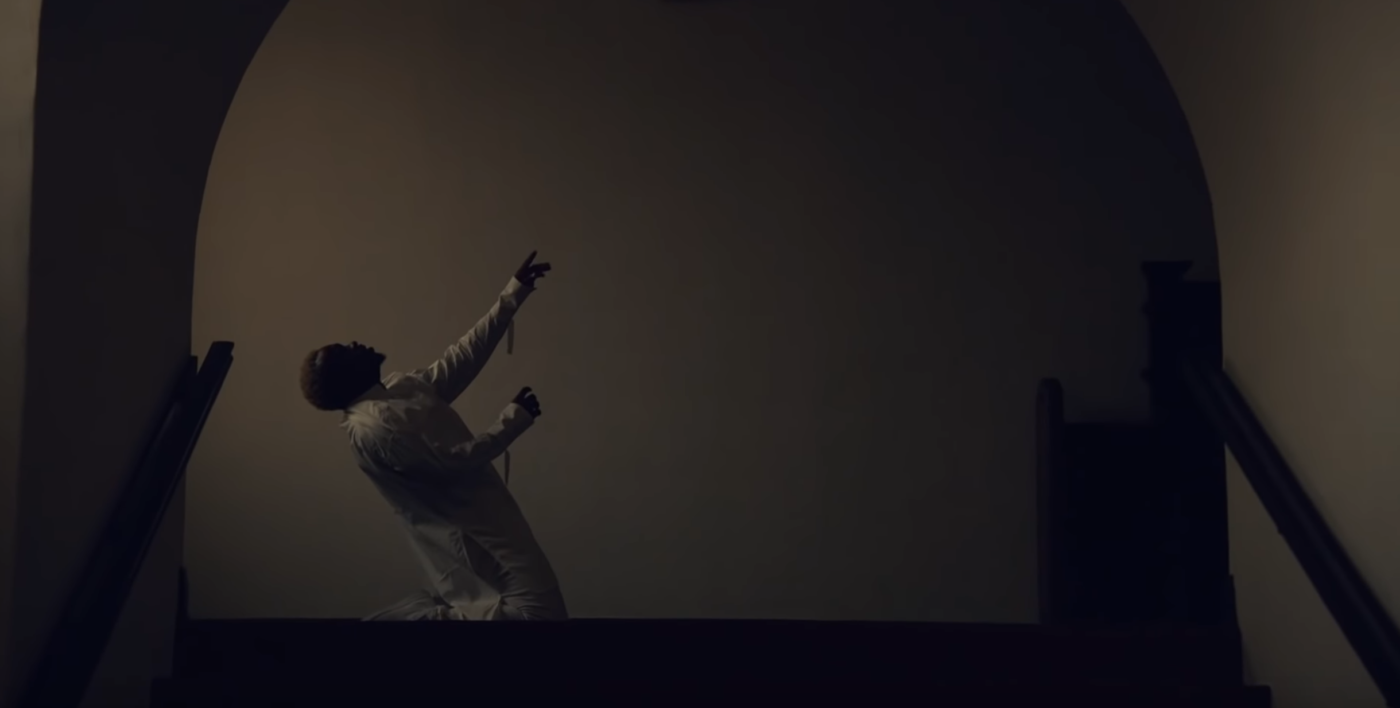

This is a Mean World: Lil Buck’s Nobody Knows by Yves Jeffcoat

We receive an amusingly wide variety of press releases in our inboxes at Burnaway, many of which fall outside of our critical purview. When I received a link to a preview of Nobody Knows, a short dance film by Memphis dancer Lil Buck and director David Javier, I was far from sure it would be relevant to the magazine and its readers. After watching it, as has become my protocol, I asked for a second opinion from our editor Jasmine Amussen. I forwarded her the link, writing, “I actually read this and watched part of the video and it’s kind of interesting… Check it out if you’re curious.” I’m so glad that she did, and that Yves Jeffcoat agreed to write about it. Now, looking back on 2020, I’m not sure that I saw any artwork that reflected the desperation and grief of this year as poetically and forcefully as this video. Of course, the film’s soundtrack, provided by Chicago’s Pastor T.L. Barrett and the Youth Choir for Christ, deserves ample recognition alongside Lil Buck’s dancing and choreography. The film is visually stunning, too: once Lil Buck departs from the sanctuary of the church where it was filmed, dancing under concave archways, the composition appears to recall the Early Renaissance painters Fra Angelico and Piero della Francesca, showing a stark contrast between the geometric architecture of the church and the dancer’s body, writhing and human.

— LL

If you enjoyed any of these stories and would like to support Burnaway’s editorial and programmatic work, consider making a year-end contribution or joining our membership program.