Patricia was the first member of the Satterwhite family you met upon entering the Chelsea location of Mitchell-Innes & Nash. You heard her singing over the speakers and saw her handwriting transcripted into bright neon signs and handwritten notes hung with archival care. You interacted with Patricia’s ideas before you saw the work of her son Jacolby, whose innovative work in sculpture, video, and music transferred Patricia’s visions into the digital age in his recent exhibition We Are in Hell When We Hurt Each Other.

When Patricia died in 2016, she left behind an entire archive of her art, music, and writing. Raised in Columbia, South Carolina, Jacolby Satterwhite now lives in Brooklyn and has been the subject of solo shows at Pioneer Works, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and the Fabric Workshop in Philadelphia. Though Satterwhite has departed from his family home, his childhood in South Carolina and his identity as a queer, Black, Southern artist continues to influence his work in monumental ways. In an interview with Evan Moffit of Frieze, Satterwhite described his mother as a “mentally ill” but prolific folk artist who “over the course of her life, recorded seven albums and made over 10,000 drawings… She was making these drawings with an enigmatic language like a Gertrude Stein poem.” As he came into his own as an artist, he made a conscious decision to look to his mother’s restless multimedia practice: “I realized that Patricia Satterwhite was the artist hero I should have had all along. So, I decided to make her a rubric for the way I thought about art. That’s why I began performing. The first thing that struck me about my mother’s language was that her words appeared to be scores, and since all of her drawings were about objects, I connected that to the way bodies perform in space.” 1

We Are in Hell When We Hurt Each Other was contained to a single room, with the nearly clinically white and incredibly high ceilings of Mitchell-Innes & Nash showcasing the artist’s three-dimensional video and neon installations. The single square room of the gallery also highlighted the refractive quality of Satterwhite’s work: the way these works interacted visually drew attention to different details and vantage points within a single moment. This particular moment was brought to life in the exhibition’s eponymous video, which is framed by one of Satterwhite’s sculptural works, Room for Levitating Beds (2019). The elaborate video simultaneously evokes Final Fantasy and ballroom culture, with robots dancing to the pulsing electronic beat of PAT (the musical project of Satterwhite and Teengirl Fantasy frontman Nick Weiss that remixes the songs written, sung, and recorded by Satterwhite’s mother). Along with the artist’s own presence, a few familiar figures inhabit Satterwhite’s animations, such as supermodel Bethann Hardison, who reigns over the proceedings in a regal red cloak. The end of the video features the army of robots positioning themselves around a tribute to Breonna Taylor, the twenty-six-year-old ER technician murdered by Louisville Police this March.

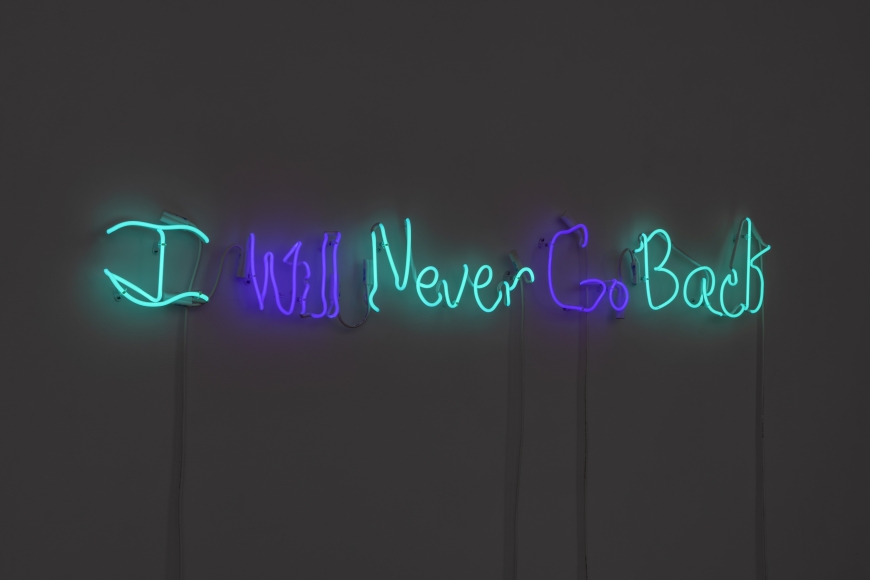

The figures and motifs in this video repeated across the exhibition, often combined with potent art historical imagery that further signaled Satterwhite’s desire to play with artistic archives: Bethann Hardison’s omnipotent gaze reappears and multiplies in Black Luncheon and Pygmalion’s Throne—the image of Hardison itself recycled from Satterwhite’s visuals for the September 2020 issue of Interview magazine. Satterwhite reused the title Black Luncheon for a large neon installation combining Patricia’s drawings with Édouard Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (1863). Positioned similarly within the composition to Manet’s original bohemians, three figures sit as a baby floats above them. A comically animated, Lichtenstein-esque BOOM! is connected to the child via a bright red umbilical cord. Satterwhite also uses neon for figurative purposes in Doubt, where anatomically simplified and naked male figures adorned with technology from Patricia’s drawings admire one another in a position that reads like a moment of biblical realization akin to a Renaissance-era Annunciation. Across the room stood a three-dimensional sculpture of Doubt—now entitled Room for Doubt—bringing a new focus to the futuristic details of the original drawings and featuring footage of Satterwhite’s early performances on the monitors attached to the figures’ torsos. These figures were surrounded by 3D-printed resin sculptures of the objects Patricia drafted, faithfully reproduced by the cutting edge tools used in Satterwhite’s practice.

Like with Satterwhite’s earlier projects, there was an undeniable sense that We Are in Hell When We Hurt Each Other was the work of two artists—traversing across generations and death itself to imagine futures unencumbered yet absolutely informed by the troubles of the world as we know it. Satterwhite readily evoked his mother’s spirit as a collaborator, and his body of work is a loving tribute, contextualizing her as the visionary artist she was and continues to be through her son’s practice. Her voice, both metaphorically and literally, is inescapable despite the absence of her worldly presence.

In his 1994 text “Spectres of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning and the New International”, Jacques Derrida wrote “to haunt does not mean to be present.” 2 Although the intentions of this work were to explore the role of historiography and historical context following the collapse of the USSR, Derrida’s analysis of the remaining, powerful presence of historical memory and moment as tied to communism—named “hauntology”—has been used to understand the presence of familial, artistic, and sociopolitical histories that linger in art objects. 3 It’s the family photos mentioned in bell hooks’s essay “In Our Glory: Photography and Black Life.” It’s watching Hannah Wilke’s Intra-Venus Tapes and knowing that the woman on screen is dead. And it’s even something like the phone calls interspersed through Frank Ocean’s blond—a reminder of family and youth that lingers unresolved and ever-present in the psyche.

We Are In Hell When We Hurt Each Other is a recalibration of Derrida’s hauntology to redefine “the haunt” and specterly manifestations in the context of the digital archive, considering the paradox of presence and absence it affords us. Although rendered to theatrical heights, the scenes created in Satterwhite’s animations seem to exist in a not-too-far-away future, admittedly a future more utopian than the world in which we currently live. Digital technology—whether in these alternate worlds or in our daily lives—redefines the scope of memory and opens up possibilities for an archival practice driven by remembrance and care. The digital archive Satterwhite has created to complement and preserve his mother’s art allows her to exist beyond death, collapsing our views of time as a linear and static entity. Satterwhite’s trans-temporal evocation of Patricia’s archive carries an undeniably political charge in an anti-Black, misogynistic, and ableist world. Looking back to elders—whether political forebears or deceased loved ones—and crafting a simulacrum of their ideas and ideals imbues their voices with new resonances, especially considering the number of visionary women such as Patricia who were erased by a society built against their survival. In a digital world, perhaps death is optional if your ideas survive, and in Jacolby’s animations, sculptures, and installations, the Satterwhite family endures against all (analog) logic.

1 Evan Moffit and Jacolby Satterwhite, “Body Talk,” Frieze, published April 11, 2016.

2 Jacques Derrida, Spectres of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning and the New International, London: Routledge, 1994.

3 Mark Fisher, “What Is Hauntology?,” Film Quarterly 66, no. 1 (2012), p. 16-24.

When Are In Hell When We Hurt Each Other was on view through October 31, 2020 at Mitchell – Innes & Nash, New York.