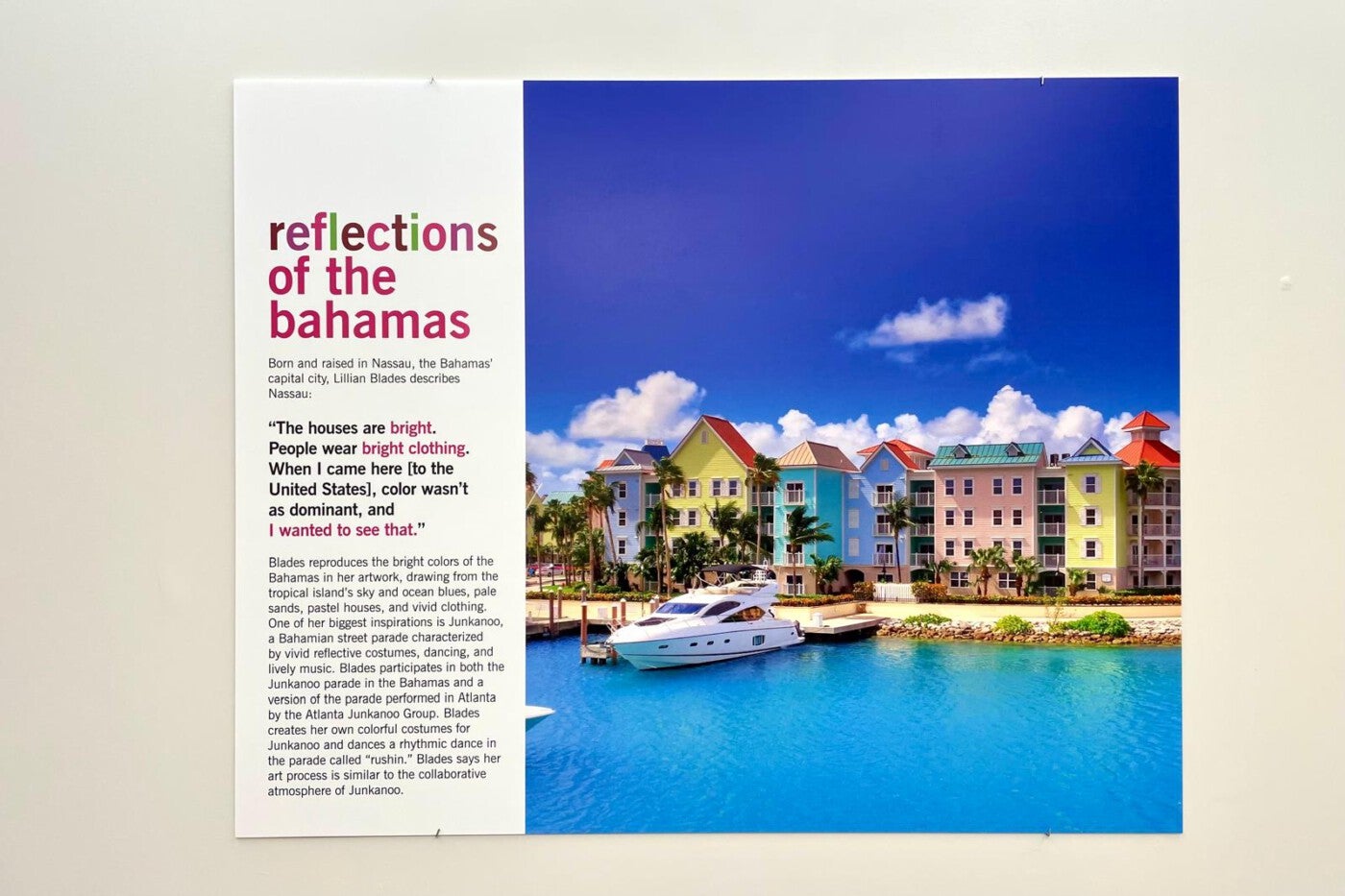

Orchid Daze, an exhibition at the Atlanta Botanical Garden, features new work by Atlanta-based Bahamian artist Lillian Blades. Each year, the garden collaborates with an artist to celebrate its orchid collection. Four installations, collectively titled Reflections in Bloom (2024), build on Blades’ signature assemblages that formally reference Junkanoo[1] and quilting, honoring her mother’s background as a seamstress. She incorporates found and discarded objects, thrift store finds, and personal mementos in sprawling assemblages that speak to identity, memory, and resourcefulness. The resulting work is process-oriented and deeply considered, down to the color-matched wire used to bind objects together, a poetic gesture for the artist-meets-engineer in seeking community and connection in the oft-disjointed diaspora.

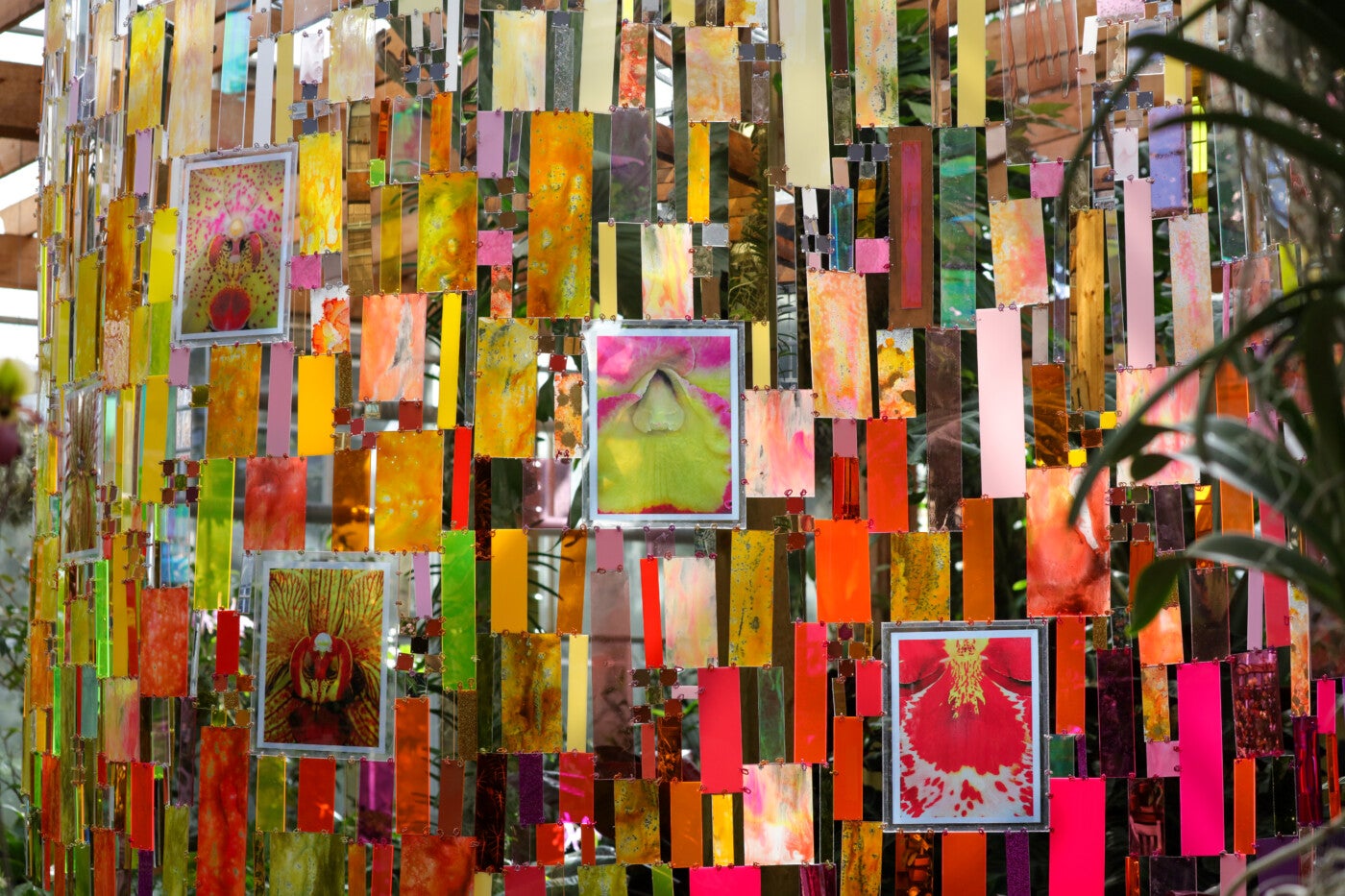

The most striking installation hangs in the Orchid Display House. Hundreds of yellow to purple plexiglass panels form an undulating gradient, delicately draping above various species of tropical orchids. Flowing gels and ink on the panels evoke fluidity, glitter refracts light, and some panels obscure your view completely while others act as chroma filters over the lush foliage. The orchids, mostly originating in Southeast Asia[2], unwittingly symbolize the colonial roots of botany as a discipline: countries sought to profit by displacing plants to produce valuable crops and eventually by curating exotic experiences in botanical gardens in centers of European and colonial power[3]. Intermittent sprinklers cloud the conservatory with a fine mist, mimicking the humidity the orchids need to thrive. This act meant to care for these plants in their non-native habitat mirrors Blades’ herself. She is a Bahamian transplant living in Atlanta, creating work as an act of care in response to the warmth and nostalgia of home. Like the structures of her assemblages, identities are mutable: fragmented yet intricately connected and deeply informed by our environments.

The placement of Lillian Blades’ work in the Botanical Garden reveals novel connections—the homage paid to Blades’ matrilineal heritage of florists intertwined with histories of colonially-rooted environmental violence creates a unique tension. Blades shares, in an audio clip in the space, that she creates work with the viewer in mind and she “wants them to feel good”; perhaps this is why the work has a sense of palatability for those unfamiliar with her context. There is also something inviting about this approach, and it makes sense given the venue. Blades is no stranger to public projects and working in unconventional spaces, and her public installations in particular effectively create networks that bridge the cultural and geographic South[4]. However, nuances may get lost without proper context.

Blades bravely uses color and hyper-embellishment, reminiscent of Junkanoo, a Black, spiritual celebration deeply rooted in anti-colonialism and West African heritage. Even this celebration has been co-opted and hegemonized by touristic marketing, which unsurprisingly informs artistic representations of home[5]. Dazzling pixels of aquamarine beaches and sweeping palms blind viewers to reality and often reduce the region to this paradise myth designed for easy consumption. This carefully constructed image of the Caribbean has become so ingrained that people from the region are no longer just passive observers of the systems that commodify them. Visitors, not unlike myself, were delighted to take selfies in front of the work and this kind of engagement highlights how the level of consideration, understanding, and context can limit or expand the work of Caribbean creatives in such spaces. Caribbean artists often bear the weight of how their work may subconsciously play into this manufactured tropical narrative (benign at best or pernicious at worst), but even more so when operating in the diaspora.

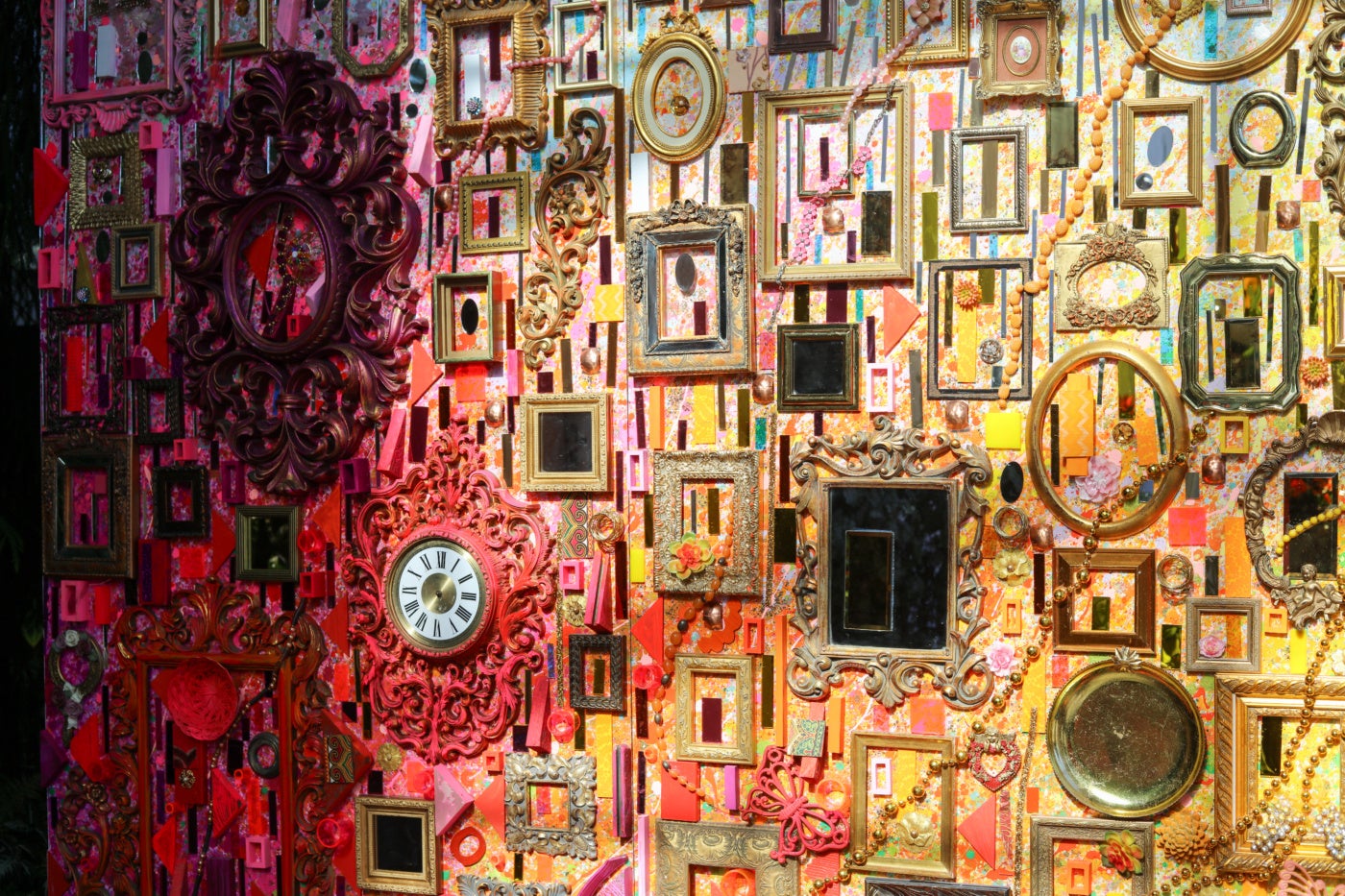

Frames and mirrors act as portals through which viewers can reflect and project their own meaning, a major focus of Blades’ practice. Achieved through meticulous arrangement and deftly shifting between moments of obscuring and revealing, the rich bricolage becomes a metaphor for the constant (re)presentation and renegotiation of self. This translation is itself an innately Caribbean experience. Blades manipulates the color palette we have come to associate with the Caribbean to induce the idea of a filter[6]. As the sun passes through one chandelier-like installation, its purple and pink hues imbue the space and saturate the skin, challenging perceptions of reality and ways of seeing. These occurrences bring forth necessary questions, particularly for those living in the Caribbean diaspora: How does one construct an image of home when that image has been tampered with? What exists in the obscurity between representation and reality? Where and how do I fit into this patchwork? Lillian Blades’ work allows visitors to contemplate their journey of self and place through this prism.

[1]“In the Bahamas, Junkanoo, a Christmas festival, which portrayed modest costumes of sacking, sponge, and newspaper in the 1920s and 1930s, now display elaborate costumes of cardboard, styrofoam, and colored crepe paper with groups hundreds-strong with drums, cowbells, and trumpets and large brass sections.” (Gail Saunders, “The Changing Face of Nassau: The Impact of Tourism on Bahamian Society in the 1920s and 1930s,” NWIG: New West Indian Guide 71, no. 1/2 (1997): 21–42)

[2] Paphiopedilum victoria-regina is a tropical Asian slipper orchid that grows in rocky crevices on cliffs 800 – 1,600 meters elevation on the Indonesian island of Sumatra. Named for Queen Victoria, it was first imported to England in the 19th century.” (“Paphiopedilum victoria-regina”, Atlanta Botanical Garden, accessed March 23, 2024, https://atlantabg.org/plant-profile/paphiopedilum-victoria-regina/)

[3] “Orchidomania and orchidelirium—terms used since the nineteenth century—capture the obsessive pursuits of orchid hunters and lay public alike who were driven to collect new orchids from dangerous yet environmentally fragile locations and devote their lives to their cultivation.” (Erica Hannickel, “Introduction” Orchid Muse: A History of Obsession in Fifteen Flowers (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2022), 1.)

[4] Blades’ public projects include the Hartsfield Jackson Atlanta International Airport, State Farm Arena, Baha Mar, Publix Greenwise, and the East Atlanta Library, among others. Her work is also a part of the collections of the Birmingham Museum of Art and the National Art Gallery of The Bahamas. (“About” Lillian Blades, accessed March 28, 2024, https://www.lillianblades.com)

[5] “Of course, the Bahamian artist’s representations of home are informed by yet another colonizing force, that of tourism and its highly marketable conception of the Bahama Islands as places not only of natural beauty but also of bliss, innocence, forgetfulness, and tranquility.” (Ian Strachan, “Goin’ Back ta Da Islan’: Migration, Memory and the Marketplace in Bahamian Art.” Yinna: Journal of The Bahamas Association of Cultural Studies 2 (August 2007): 32.)