Courtesy Institute 193, Lexington. © Guy Mendes, 2019.

Time slips away and leaves you with stuffing.

Bruce Springsteen if he’d say what I want him to say.

The Kentucky Museum of Arts and Crafts (KMAC Museum) is hosting an exhibition called Where Paradise Lay, a phrase I can only trace back to John Prine’s song “Paradise,” which tells about an extractive coal mining business laying waste to a county in Kentucky. The exhibition is adapted from the 2019 book Walks to Paradise Garden, a previously unpublished manuscript chronicling the travels of poet and publisher John Williams and photographers Guy Mendes and Roger Manley, whose stated aim was to document the lives and work of Southern outsider artists “who live on the heath.”

If this were my aim, I would set up a booth on the heath and interrupt anyone crossing it with their skirt bunched into their hands. “Outsider artist? No, no. I am just on the way to meet my lover.” This classification is loose and moving, like “the heath.” Perhaps the classification of “outsider artist” relies on the peripheral vision of the photographers, who see that the sediment is raining granular through the floorboards, and they better catch it! They must document the basement works that might be lost to the Salvation Army or some trash heap if people did not see them and believe in them. In other words, their aim was to fortify the works against what Prine’s song describes as “the world’s largest shovel.” And, of course, I imagine they wanted people to enjoy them.

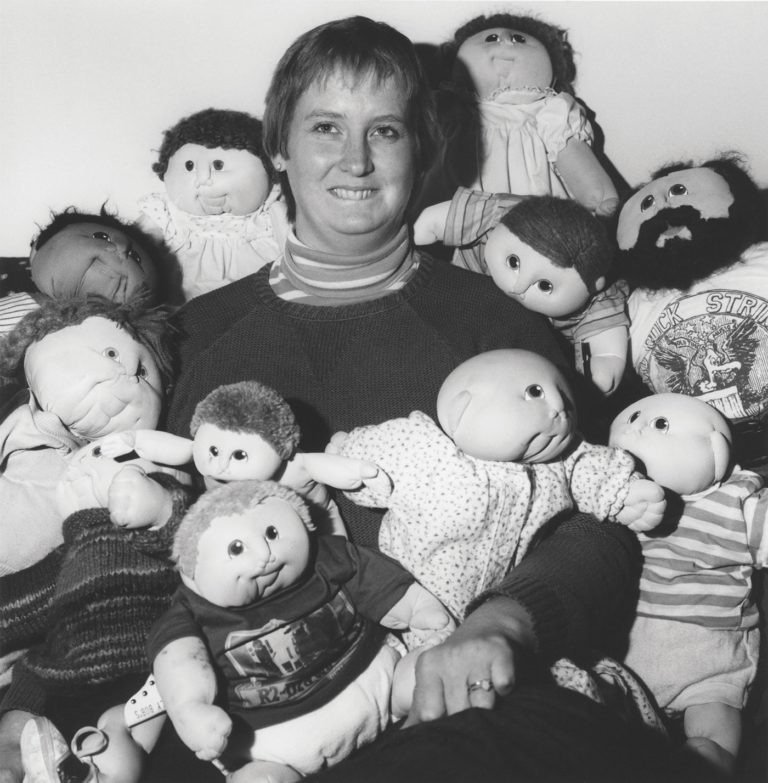

I was drawn from my dwelling to Louisville by the promise of seeing Martha Nelson Thomas’s soft sculpture dolls, which are featured in Where Paradise Lay. I have yet to call a woman in my family this season who did not make dolls patterned after hers: my mother, my Aunt Neal, and my Gran. This says something about the communicability of certain art forms and, obviously, about dolls themselves. Even a mass-produced doll takes on its own particular attributes through the imagination of its owner. But people wanted to make Thomas’s dolls, and they could. I am impressed.

On the second floor of KMAC Museum, two unattended baby dolls made by Thomas are on display in a glass case. They are sculptures waiting, dormant in their neediness. This feels like the truth about dolls: that they are matter made in the likeness of neediness, and they are only woken by being somebody’s baby. Actually, I can tell that Baby Otis and Baby Jeremiah are definitely somebody’s babies. Both babies have some amount of dog hair on them. They are made of pantyhose, the grain of which runs asymmetrically across their scalps, looking as though fabric has gridded their skin during a nap. Their necks are gathered into their chests, and a scalloped hem runs beneath each doll’s chin. These babies are neckless, sprouted. They look like henchmen, like turtles freshly scraped from their shells. Their arms spring right from their shoulders, outstretched in the posture that says, alternately, Pick me up! Hold me! Chest bump me! Crucify me! depending on who you happen to be. Their toes point towards their knees. They are deeply dimpled. Their cheeks are rouged, and there is a slight tear on Baby Jeremiah’s cheek. Baby Otis is wearing a yellow T-shirt that says Lizard Patrol, and a studded lizard brooch is pinned to it. The baby is in possession of a brooch because someone left him. A woman? A mother on a train? It is a reminder of his origin. He was formed in piercing.

Both babies’ wrists are bound and cinched like bow-tie pasta. Their hands are formed so that each shows a fat portion of the palm, crossed by tulip-shaped lines. Though they are wearing real baby clothes and real baby shoes—their soles shiny with wear—I find their hands most convincing. I want to unfurl them, and I know when I do I will find something that is a mixture of wet and crunchy, the texture of a parking lot after it rains.

Julie Baldyga’s show Heavenly People is located on the third floor of the museum. Baldyga has a longstanding infatuation with hands. An oil pastel portrait of Hadley, a friend of her brother, shows a young man standing and looking out the window. The floorboards in the picture are not shrunken with any kind of perspective, and each is laid intact on the next. The young man’s white shoes are tilted up towards the baseboards. The apples on the tree outside the window are energetic and multi-directional in mid-fall. The situation looks mathematical, almost Newtonian. The young man’s hands are posed behind him as though someone is about to place a loaf of bread in them. They are outsized, and the fingers are relaxed and staggered. They bloom like paisley. His hands frame his bottom which, like the floorboards, is flat and precisely rendered. Julie, might I bring you into this? My favorite thing about men’s forms is the way their wide hands fall beside them like puppy paws in a boat’s wake. The fellow’s forearms are lined with veins that look like wires. I admire Baldyga’s ability to pick something and collect it. Julie collects wires.

This young man’s hands are most the compelling part of the picture. The hands are outlined starkly, and Baldyga—like Martha Nelson Thomas—is most attentive to the major and minor portions that make up hands. It is my opinion that the figure looks like a grown-up version of one of Thomas’s Doll Babies. His hands look ready to hold something, but they also look as though they might have released something. They lightly grip in the same kind of body memory that makes a man susceptible to Juuls and toothpicks.

It appears to me the memory of a Thomas-like babyhood is carried seamlessly through to adulthood by Baldyga. It feels appropriate that the two works were created by two artists and yet, in my imagination, describe one person. I hear stories about myself as a baby, and the things I learn feel blessedly consistent and surprising. It does not feel, however, like that version of me was by me. One is myself, and the other is beyond my memory, maintained by people who’ve known me since I was a baby. The things binding together my present self and my previous self are the fact of my body and the stories I hear about my nascent person. This is how I see the two stories being told by Baldyga and Thomas, why they might describe one person. Childhood and adulthood feel like stories written by different people, and beauty arrives in the ways—through the exquisite corpse game of building an identity—the lines meet up.

Martha Nelson Thomas was insistent that her Doll Babies were real babies. She crafted adoption certificates for each of them. Xavier Roberts purchased her dolls and began to sell them at an upcharge in a crafts store he was managing. Thomas asked him to stop, and he began to make his own—meaning he signed their butts! He eventually created the Cabbage Patch Doll brand, along with a mythology centered on himself. I found a cardboard Cabbage Patch Doll sticker book that begins, Many years ago a young boy named Xavier Roberts happened upon an enchanted Cabbage Patch™. He eventually purchased what was once a real medical clinic in Georgia and turned it into Babyland Hospital, where babies were “born” and could be “adopted.” But now, at KMAC Museum, it is more like a real hospital. The gallery attendant screens visitors with a temperature gun.

At Martha Nelson Thomas’s funeral, anyone who owned one of her dolls was invited to bring it, and they were lined up on a pew in the front row. Julie Baldyga also created a host of soft sculpture people, the Heavenly People. Larger than life, they are structured with bamboo, stuffed with grocery bags, and wrapped in cheesecloth. On top of this, they are painted, coated in body hair, and given nails and accessories. She sprays each with perfume. Their nails are made of cut pieces of plastic, and these nails are all painted with sheeny paint. They wear wigs, sunglasses, flowers, and brooches. That lizard brooch! The people slump together on a pew, hands on each other’s knees like lovers in a diner booth.

If you subscribe to the theory that when you die you return to wherever you were before you were born, you probably agree that this place is stubbornly beyond memory. The Heavenly People and the Doll Babies are close to the bookends of memory. I want to unlock the iron gate at the mind of a Heavenly Person.

“Oh, you don’t remember much, Jeremiah. Let me tell you about a time when you were a baby. I can describe you for you and let you know you know how continuous you are, how this feels like love.”

I will never get over the lizard brooch. It feels like a baton handed between the Doll Babies and the Heavenly People, allowing me to complete my mental lap. Fill the pail with observation, and empty it to water the garden. Time slips away and leaves you with lots! Wads of hair and a lizard brooch sunken in the pail.

Where Paradise Lay and Julie Baldyga’s Heavenly People are on view at the KMAC Museum in Louisville through November 8.