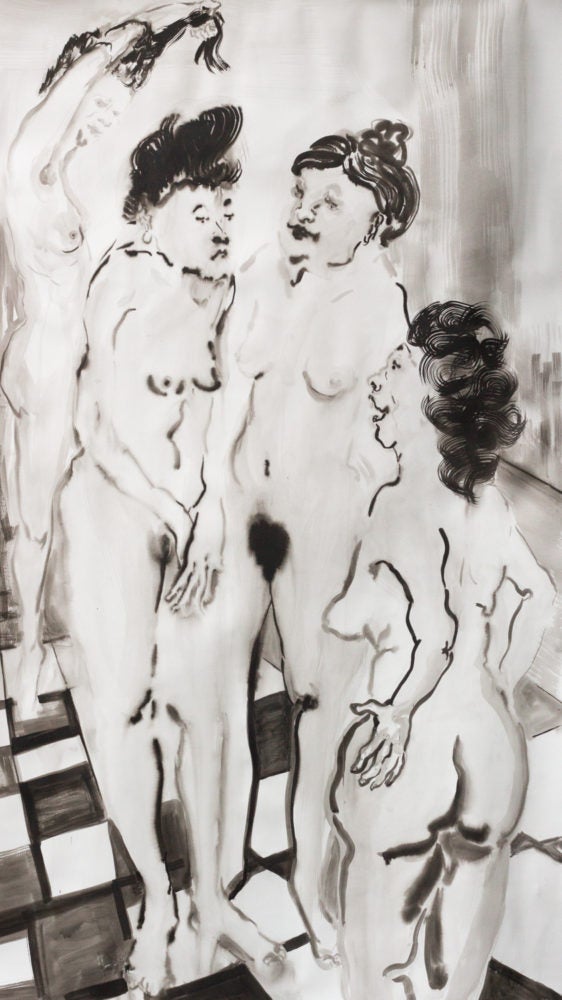

When I spoke to María Korol about her project for Mood Ring, she was grappling with the new guidelines effectively banning Americans from entering Europe, leaving her without access to work and exhibitions she had planned in Berlin and elsewhere. Our conversation was wide ranging: we discussed the national drink of her native Argentina (Fernet and Coca-Cola), her teaching job at Agnes Scott, what it means to obscure or reveal women’s bodies. She had been reading a lot about Zwi Migdal, the organized sex-trafficking ring that exploited poor Jewish women from the Eastern Bloc and brought them to Buenos Aires and other parts of South America. Her artist project for Mood Ring probes this movement—forced and unforced—the power and violence inherent in the bodies of women, and the illusion of control in perverse isolation.

In this installment in the magazine’s artist column Mood Ring, Burnaway presents new drawings and poems by Korol for the first time.

— Jasmine Amussen

Herramienta

Genero en mi imaginación

su cuerpo y el mío

acostados lado a lado.

Como usando una herramienta de photoshop

pegando y abriendo mi pulgar e índice

agrando y achico el tamaño de cada uno de mis senos

y el de su miembro.

Alargo mis muslos, afino su cintura,

adelgazo el grosor alrededor de mis rodillas

y relleno la musculatura de sus brazos.

Una casa del barrio

es muy fea por fuera y muy linda por dentro. Como yo.

Él me elogia

que no,

que es al revés.

Tool

In my imagination I generate

my body and his

lying next to each other.

As if using a photoshop tool,

sticking together then opening my right thumb and index fingers,

I make each of my breasts bigger or smaller,

I expand and shrink his sex.

I elongate my thighs, thin his waist,

reduce the width around my knees,

fill up his arm muscles.

In the neighborhood a house

is very ugly on the outside but beautiful inside. Like me.

He flatters me

that no,

that it is the other way around.

Ariadna

Ariadna en su laberinto

camina hacia arriba

va al cuadrante izquierdo

resbala por una línea azul

se desplaza a través de una abertura

hacia el área verde baja

del espacio que habita.

Un moverse no necesariamente físico

un flotar de demerol.

Ariadna en una calle de Caballito

mirando un edificio del siglo XIX

que es la escuela secundaria adonde fué

por dos años, no se hizo ni un amigo,

estudió gramática histórica (en el pasado hormiga se decía formiga)

La maestra tenía anteojos culo de botella, canas y caspa,

como Ariadna ahora.

En la bicicleta vieja de su papá

con dolor de espalda

llega casi siempre tarde

con lagañas en los ojos y mal peinada

con desolación

apenas escondida.

El papá se queda durmiendo

después de otra borrachera.

En la mañana escucha a Bob Marley,

al mediodía admira a Dalí y a Andy Warhol,

por la tarde abandona a un psicoanalista

porque le dice que está varado en sus diecisiete.

Ariadna en su ciudad es invisible

en su laberinto acomoda las piezas,

organiza las partes,

se desplaza al cuadrante izquierdo

resbala por una línea azul, flota.

Donde no está,

puede moverse.

Ariadna

Ariadna in her labyrinth

walks upward,

goes to the left quadrant,

slides on a blue line,

displaces herself through an opening

to the green low area she inhabits.

A movement that is not necessarily physical,

a floating as if on demerol.

Ariadna in the Caballito neighborhood,

looking at a building from the XIX century

that is the high school where she went

for two years, where she made no friends,

and studied the history of grammar (in the past the word “hormiga” was “formiga”).

The teacher had four eyes, white hair, and dandruff

like Ariadna now.

On her father’s old bicycle,

her back aching,

she arrives almost always late,

boogers in her eyes and her hair badly done,

her desolation

barely hidden.

Her father sleeps late

after another drunken night.

In the morning he listens to Bob Marley,

at noon he is fascinated with Dalí and Andy Warhol,

in the afternoon he quits psychoanalysis

when he is told he is stuck in his seventeens.

Ariadna in her city is invisible.

In her labyrinth she arranges the pieces,

organizes each part,

displaces herself to the left quadrant,

slides on a blue line, floats.

She is able to move

where she is not.

Regreso

Decido volver por el camino por donde vine,

todo se me deforma al retroceder.

Al abrir la puerta la sala es mucho más grande,

las paredes son más rojas, el sillón más antiguo, su tela más aterciopelada.

Por la ventana del primer piso

veo que el jardín de abajo tiene más plantas,

la reposera es de los colores de la bandera francesa,

y una manguera me sirve para jugar a She-Ra

haciendo girar al agua alrededor de mi cuerpo.

Ya tengo el poder.

Mi papá lee a Bukowski

yo leo a Bukowski.

Una nena de mi edad es observada por un viejo desde una ventana,

la nena es ultrajada por el viejo,

a alguien le tiemblan las manos.

Me miro las palmas,

mis dedos gordos están del lado de adentro.

Return

I return using the same path that brought me here,

everything is deformed as I move back.

I open the door and the living room is much larger,

the walls redder, the couch older, its fabric more velvety.

From the second-floor window

I see that the first-floor garden has more plants than before,

the lounge chair has the colors of the French flag,

and I can use the hose to play She-Ra,

making the water swirl around my body.

I have the power.

My father reads Bukowski.

I read Bukowski.

A young girl my age is observed by an old man from a second-floor window,

the young girl is disgraced by the old man,

someone’s hands are trembling.

I look at the palms of my hands,

my thumbs are on the wrong side, next to my pinkies.