Sometimes it’s easier to experience something than to describe it. As the curators of The High Museum of Art’s current exhibit, What is Left Unspoken, Love, frequently remind us, such is love. In fact, if you were to walk through the exhibit without reading the accompanying text, you might not come away certain of its intended subject. In many ways, not bothering with the written component of this exhibit may be the best way to experience What is Left Unspoken, Love, which is full of brilliant, often show-stopping, pieces. The curators’ attempts to contextualize the work under the blanket thesis of “love” often leave much to be desired, and the exhibit can seem somewhat cobbled together as a result. This is not entirely their fault, of course. It’s practically impossible to capture something as multi-faceted and all-consuming as love, something not lost on this reviewer. As musician and artist David Byrne reflects in his 1986 self-interview for the concert film, Stop Making Sense, “I try to write about small things: paper, animals, a house. Love is kind of big.” Indeed, in this case, love seems too vast a subject to confine to the written language. That can be forgiven. Quoted in the exhibit, poet and painter Etel Adnan reminds us, “Love is ‘not to be described, it is to be lived.’”

Uninspired efforts to describe the enormity of love aside, this is a breathtaking show. The curators organized nearly seventy works by thirty-five international artists into six categories, or expressions of love—romantic, familial, self, communal, poetic, supreme— some more convincingly than others. Though the curators admit that sometimes the categories contradict or negate each other, the overall message that there are different types of love encompassed within the human experience comes through.

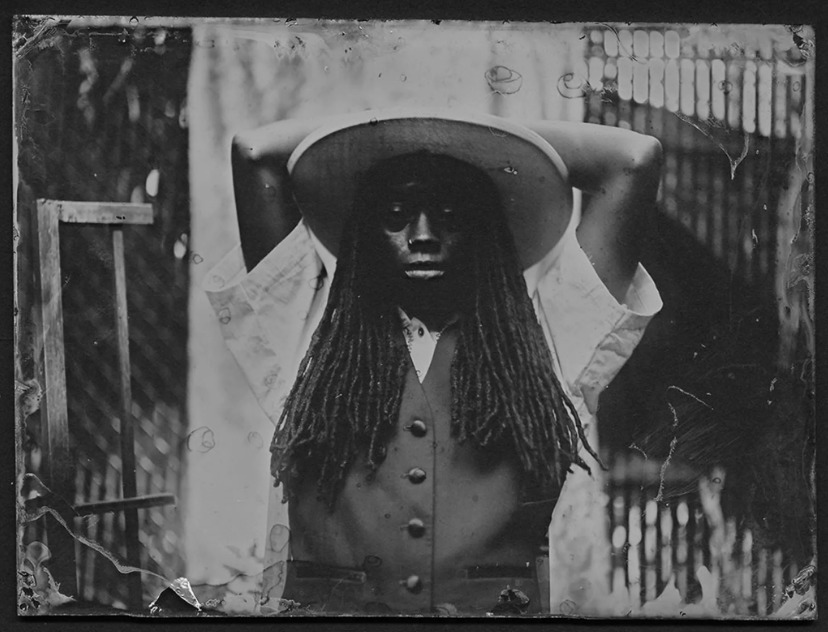

A few works do demand even more careful and considered viewing. In a powerful display in the “familial love” category, genderqueer and Afro-Latinx artist Felicita Felli Maynard presents Ole Dandy, the Tribute, a series of gelatin silver prints that imagines queer historical roots for two drag kings in the late nineteenth century. That they are fictional drag kings doesn’t matter. Maynard’s imagined kings are made real through the art, and their valid history is made observable through these prints. There’s something intensely personal about the works, too, as we watch each drag king transform through a series of panels from one gender to another. Maynard manages to make the invisible visible with this detailed recreation of a secret history. Indeed, with Ole Dandy, the artist triumphantly corrects the official record with an imagined queer historical representation.

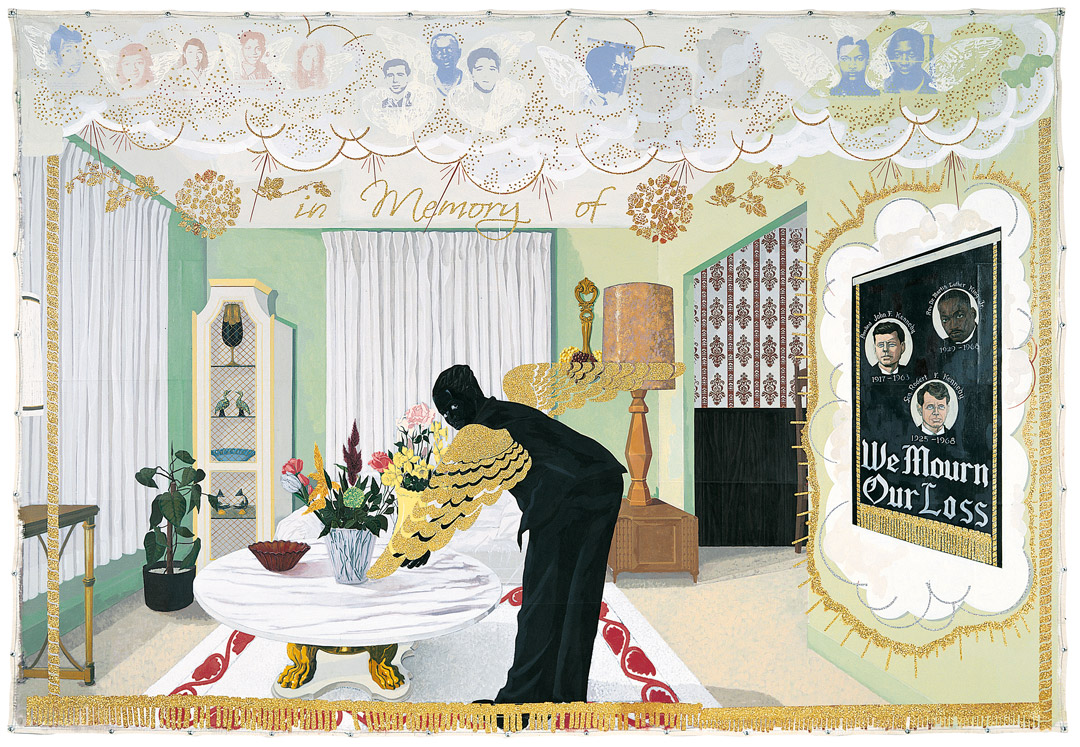

In a room built around the theme of love in community, the curators have included what is perhaps What is Left Unspoken’s strongest moment: Kerry James Marshall’s moving and mysterious Souvenir I. Executed on an un-stretched canvas and hung by grommets like a processional flag, the painting features a view of the typical post-Civil Rights Era Black household living room. The room’s décor includes the holy trinity of martyrs (JFK, Robert Kennedy, and Martin Luther King, Jr.) depicted on a banner on the wall, and lesser known victims of the era’s violence floating with angels’ wings in a frieze along the room’s ceiling. The dichotomy of public and private memorialization provides an extra layer of meaning to the piece, which is in the permanent collection of The Met. At the center of the room stands a monolithic Black figure, a woman, who appears surprised by the viewer in a private moment, or interrupted in her domestic chores as she arranges flowers on the table. The Black woman, partially turned away from us, has golden angel wings, too. Is she the Angel of Death tending to a shrine? Or is she, as the curators suggest, “an enlightened witness”?

Typical of Marshall’s work, the angel’s Blackness obscures her features in a play between visibility and invisibility, and as she is interrupted in her domestic obligations, Marshall pays tribute to the Black women of the movement, often overshadowed by the giant public figures on the wall. Interestingly, Marshall has called the Souvenir series a collection of “annunciation” paintings, referencing the Christian story of the angel Gabriel’s proclamation to Mary that she would give birth to the savior. In this light, the matron’s wings may signify a new “annunciation,” perhaps of a new savior who will make Martin Luther King’s “beloved community” a reality. Interestingly, though this piece is presented in the category of “communal love,” no mention is made of the beloved community in the work’s description. Instead, the curators interpreted the woman’s direct gaze as “welcom[ing] us into the picture or [asking], ‘Where do you position yourself within this history, within this struggle?’” By engaging the present with the past, Marshall masterfully highlights the current movement and continued struggle for equality.

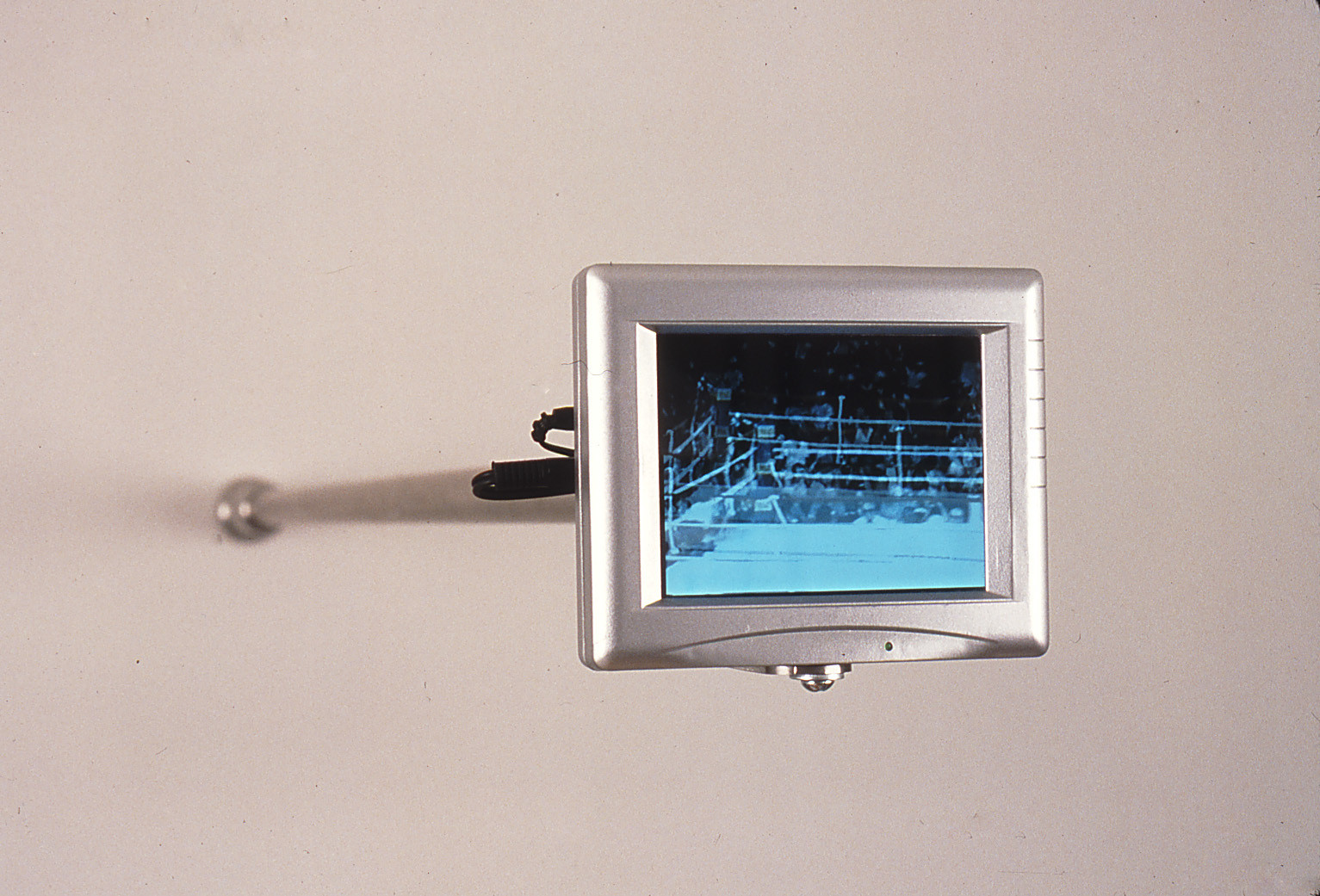

What is Left Unspoken, Love’s stated themes of “human destiny” and divine, or supreme, love towards the end of the exhibit seemed the weakest, although those themes were called into question in interesting ways by Paul Pfeiffer’s small video installation, John 3:16, in the penultimate gallery. Pfeiffer’s work often incorporates sports footage to allude to French Marxist philosopher Guy Debord’s “society of the spectacle,” a highly influential theory that our present world and the supposed unifying experiences within it, such as religion or sports teams or even museums, are not based in reality, but are simply empty symbols and simulacra on screens. The curators suggest that these things actually estrange people, rather than bring them together, and reveal an inescapable hollowness in society. The title of the video refers to the well-known Christian verse in which mankind is redeemed through God’s love, and which was also common to see written on signs held by sports fan in stadiums in the early 2000s, when the piece was made. For Debord and Pfeiffer, questions immediately arise as to whether such a “profound meaning can be conveyed in a context where, as [Debord] says, ‘love can be juxtaposed with almost any image or product to make a compelling visual statement because what you are really looking at, really affected by, is nothing more than the spectacle.’” For a moment in Pfeiffer’s tiny screen, the viewer is asked to question the entire exhibit: Is all of this art, which attempts to express the inexpressible about the human experience, merely part of the simulacrum? Are we all fortune’s fools?

That would be a really depressing piece to choose to usher us out of an exhibit about love, wouldn’t it? Thankfully, the questions raised by Pfeiffer’s work are answered by the final work in the show, Rafael Lozano-Hemmer’s 2006 installation, Pulse Room, a true visual spectacle to behold. A grid of hundreds of incandescent light bulbs suspended from the ceiling blink and hum, each one according to a previous visitor’s heartbeat, recorded at a station at the back of the gallery space. There, a computer and heart rate sensors document a single visitor’s pulse, depicting it first in isolation in the lightbulb closest to the visitor and sensors. Then, one by one, the previous recorded heartbeats embodied in each lightbulb through blinking lights join in cacophonous harmony and a stunning strobe effect. The result is marvelous, as a literal human body orchestra plays a universal chorus that has both elements of form and chaos to it, the material heartbeat becoming a symbol of spiritual connection. The grid of heartbeats above the viewer invokes an omniscient view of humanity, with its individual neuroses and superficial differences lost in the void.

What is Left Unspoken, Love is on view at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta through August 14, 2022.