In tarot, the Fool—the first card in the Major Arcana—is a sort of holy trickster, the antecedent to the Joker in modern playing cards. I often read the Fool as a sign of mutability, a figure representing openness to change, and as the almost universal protagonist of the archetypical story told by tarot, a potential stand-in for anyone.

For his solo exhibition The Fool-ectomy, artist Mac Balentine—an MFA candidate at the University of Georgia’s Dodd School of Art, where the exhibition is on view through October 4—draws upon these associations with the character but also upon a much wider body of Renaissance literature concerning the Fool, Das Narrenschneiden. Continuing his interest in the history of varieties of sexual expression and repression, Balentine reframes the Fool as a queer outcast, a freak and prophet who serves as a reminder of all we consider undesirable about each other and ourselves. I spoke with Balentine over the phone, and our conversation has been edited for publication.

Mac Balentine: During the past couple of years, I’ve been interested in having a more sexualized, erotic presence in my work—and that’s been helpful for me to process things personally—and it also has resonances more broadly within a range of queer sexual expression and, to a certain extent, shared experiences about how we can or cannot express an erotic energy or sexuality. I’ve been thinking a lot about how that is contextualized or situated culturally, so I reached back to the ancient Greek myth of Ganymede and Zeus, which hits on a lot of things: this idea of a male homosexual culture that was condoned by society and also, on its dual edge, this potential molestation-abduction-rape story. All of this gave me an entry into thinking about ideas of consent in sexual exchange, the historical notion of gay men as pedophiles, and the ways in which we express our sexuality at different stages in our growth.

The pederastic model of gay male relationship in antiquity was a mentoring relationship, so there was certainly an erotic element to it, but it was, however, culturally complex and part of this system meant to turn boys into men. For me, there was maybe some cultural longing for this idea of gay men helping each other grow and learn together. Last year, I did a performance as part of this work that was related to contemporary digital culture—in terms of the color scheme and some of the materials I used, which included laser cutting, digital printing, and projection—and that, for me, situated this whole history of gay male sexuality in a contemporary moment while, at the same time, viewing it through mythology gave me some distance from the present.

I further explored this idea of sexual expression and repression in the sculpture Garland, which was inspired by this so-called garland—or garlandia—that was made in Florence to cover the enormous genitals of Michelangelo’s David, which, as the story goes, completely shocked the people of Florence upon its unveiling in a public square, so they commissioned a giant chastity belt of twenty-eight bronze fig leaves to cover them. There’s no image that exists of that chastity belt, so I wanted to make a sculptural interpretation of this using the fig leaf and covering it with over twenty gallons of recirculating clear slime, eroticizing the leaves themselves and playing with the idea that the partition of the fig leaf—that veil—is erotic in and of itself.

Logan Lockner: How did these questions lead to the work in The Fool-ectomy?

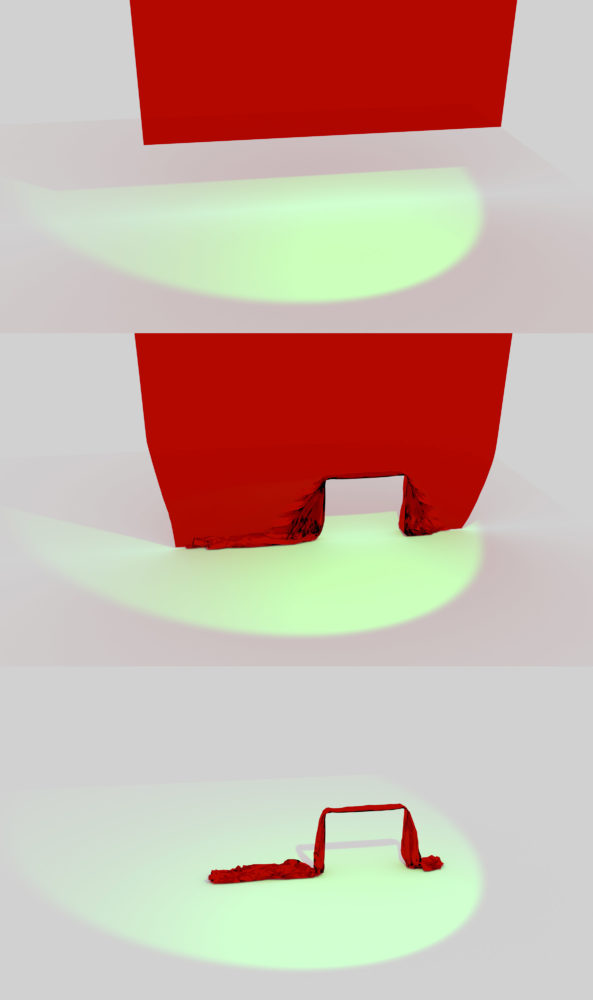

MB: I continued to work with this idea of veiling and unveiling, which is really a main structuring theme in the show. Two videos in the show, Red Veil and Brown Veil, refer to the history of veils and drapery. In sixteenth-century Italy, for example, textiles and drapery gave a lot of warmth and variety to living spaces and were an important cultural marker of wealth.

LL: So they were interior design features, essentially.

MB: Yeah. They functioned to soften a really rigid architecture. I see these veils as an almost feminine component that counterbalances this architecture. There’s a very rigid, mathematical quality to many of the tools I’m using to work in digital space, so I’ve been really interested in using digital technologies in ways that might be soft or messy, or somehow push back against or balance out these very structured and organized systems—which I also enjoy—but there’s an interplay between the two.

LL: My first association with the figure of the Fool you reference in the exhibition’s title is with tarot, but I understand there’s a whole body of literature surrounding the character.

MB: The Fool in tarot is the zero card, depicted in most common decks as a young man stepping into the unknown, sometimes off the edge of a cliff, with a joyous quality. During the period of the Narren literature in the 1500s, the Fool was a character who could speak truth to power—partially because of their willingness to enter unknown realms—but also someone who was considered unwell, and I think those two things go sort of hand-in-hand. The Fool was someone who steps outside of the agreed upon reality into a place that puts cultural norms at risk. The theory was that they were inhabited by smaller foolish persons inside of their bodies…

LL: What? Like they were demons?

MB: Kind of, but it’s unclear if it was understood literally or metaphorically. There were thousands of specific names of these different kinds of fools people believed existed. So according to this theory, these small people inside of you would have to be purged out through processes that induced vomiting, or involved enemas, and often surgical procedures. “Das Narrenschneiden,” or “The Fool-ectomy,” also translates as “The Fool Cutting,” and this idea of cutting or separation is interesting to me on multiple levels: where do I end and you begin? We separate ourselves into smaller selves, and the psyche is divided. I used collage and installation in the exhibition to address this idea of splitting a whole into parts, which is much like the function of veils as architectural partitions. So these ideas are echoed structurally and materially but also on a psychological level.

LL: It’s clear how research-intensive and detail-oriented your process is, yet your work also has a certain quality of suggestive cheekiness or humor. In different ways, your recent works have playfully explored taboos ranging from pederasty to excrement. I’m curious about whether or not you’re intentionally toeing the line of provocation or some form of irony.

MB: I’m confronting these topics because they’re things that have restricted me from experiencing pleasure. I want to make work about them in order to push through my ideas of wrongness and restore a sense of play. I’m attempting to reinvestigate things that I had cast off and find ways of turning them around in my mind. With this exhibition, I was thinking a lot about these ideas of being unwell, being disordered. The parallel to excrement primarily comes from Mary Douglas’s Purity and Danger, which argues that the way a society treats the unwell indicates its cultural ideas overall. So our society’s choice to partition off excrement, or trash— removing them from the visible realm, away from us—was something I thought about a lot. What do we do with the things we attempt to discard, even the parts of ourselves we’d rather not look at? There’s a lot of generative energy to be found in reconciliation.

Mac Balentine’s solo exhibition The Fool-ectomy is on view at the Dodd Galleries at the University of Georgia in Athens through October 4.