Festive iconography abounds in “Bandit,” Craig Drennen’s first solo museum exhibition, on view at the Museum of Contemporary Art of Georgia through January 27. Canvases draped with tinsel and sprouting miniature xmas trees jostle up against painted candy canes, globs of white snow, dollar signs, and bags of loot. Superficially, these works take a cheerful jab at seasonal commercialism. But beneath the meticulously painted trompe l’oeil bows and wrapping, they stage a far more ambitious debate over the ways that art and commerce are intertwined.

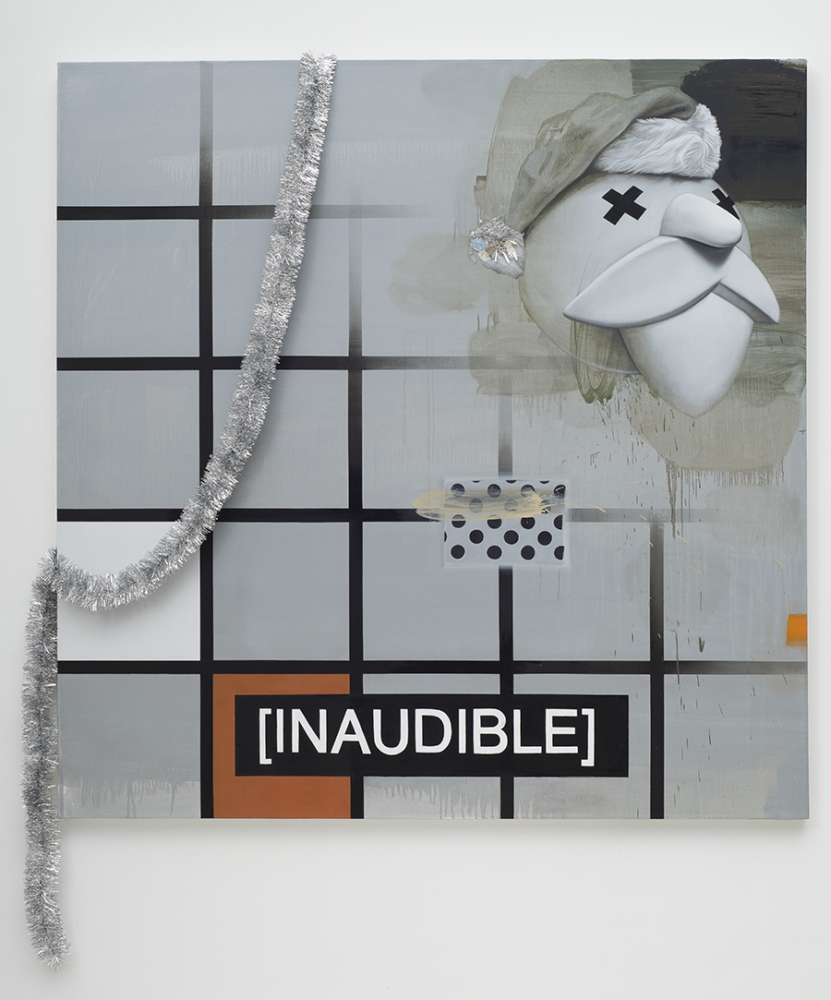

The show’s title refers to the banditti, minor characters from Shakespeare’s infrequently staged Timon of Athens. Since 2008, Drennen’s work has mostly involved painting series linked in various ways to the play’s characters. The bandits encounter Timon late in the play, when he is living as an impoverished exile in the woods, surviving on roots and nursing fantasies of revenge. Here the thieves are represented as three gray-suited, black-gloved Santas with giant X’s for eyes, splayed on the floor like a holiday morgue tableau. Their bulbous heads also appear as ornaments decorating two Grey Bandit canvases. Adding to the morbid atmosphere, a video work installed near the ceiling broadcasts a soundtrack that slurs their jolly “HO HO HO”s into a ghastly drawn-out series of sobs.

Recasting the bandits as grim Clauses is not just a seasonal tweak. In merging the thieves with the iconic secular gift-giver, Drennen highlights how beneficent acts of gifting can become twisted inside-out. In Shakespeare’s play, Timon is financially ruined through his overzealous generosity to his sponging artist friends and hangers-on. Their refusal to help him repay his debts drives Timon to urge the bandits to plunder Athens and reduce its citizens to his own pitiful condition. In a contemptuous speech, he proclaims that all things on earth, animate and inanimate alike, exist only by thieving from others.

Drennen’s bandits embody this duality of goodwill curdled into malevolence, gift turned to theft. These are never that far apart, as anthropologists have long noted. Following the pioneering work of Malinowski and Mauss, two main forms of social exchange have been distinguished: gift and market economies. Gifts are goods passed on to establish and strengthen the bonds of personal relationships, usually with the expectation of reciprocity. They have a specific, intimate value that transcends that of mere commodities. Failing to reciprocate gift-giving, as Timon’s case shows, is a violation punishable by resentment and retribution.

Markets, on the other hand, are impersonal systems for turning objects into fungible quantities of money, the ultimate transferrable arbiter of worth. Market logic rules the contemporary art world, where blue-chip galleries, auction houses, and international fairs now operate largely as an arm of the finance industry. Works are bought and sold as investment vehicles, or speculated on like coal futures. But, as Lewis Hyde points out, art has traditionally been seen as a gift from an artist to their audience, an outpouring of effort and skill that forges ties of personal affection, intellectual and emotional sympathy, and community. While artworks have always been potentially saleable, only now do the vast sums involved threaten to erode all other value they might have.

The clash between art as commodity and as gift is visible in works like Bandit 4, where painted grids establish the tension between these two modes of exchange. Grids set up a system of common measurement and quantification for everything that falls within them. It’s no coincidence, then, that Drennen’s delicately rendered bows, bells, and polka-dot wrapping paper always float ever so slightly above their cagelike surface. While grids plot the rise and fall of fortunes, gifts are what slip through the bars of capital’s enclosure.

Despite the market’s power, the art world as a community remains rooted in ties forged from affective exchanges. Artists famously show their affinities for each other through theft—or, put more primly, influence and appropriation. Drennen’s own act of artistic banditry is his reproduction of Picabia’s puzzling double portrait The Handsome Pork-Butcher as an inset in several canvases (e.g., Bandit 2), complete with white plastic combs. It’s also hard not to see his colored spots as a critical take on Damien Hirst’s, particularly when they’re adjacent to a big black dollar sign.

The bond between artist and audience, meanwhile, is now typically reduced to grabbing a quick shot of the work to post to Instagram. This slight, glancing relationship is parodied through the repeated image of a tiny figure (the artist, presumably) framed in a silver globe, like a selfie in a convex mirror. He holds up his phone to take a picture of the viewer, who is naturally delighted to reciprocate.

The works in Bandit are clever, but their wit never quite becomes caustic—they’re far too formally restrained and aware of their own references for that. Flawless technique is always slightly worrying, but in this case, at least, it isn’t mere empty wrapping. With their delicately layered colors, hyperrealist elements, tightly controlled drips, and well-composed eruptions of impasto, Drennen’s paintings are an antidote to the sloppy de-skilled provisionalism that’s still all too common. They do what the logic of the gift asks: repay your attention.

“Bandit” is the result of Craig Drennen’s Working Artist Project grant from MOCA GA.

Dan Weiskopf is an associate professor of philosophy and an associate faculty member in the Neuroscience Institute at Georgia State University. He is the author, with Fred Adams, of An Introduction to the Philosophy of Psychology (Cambridge University Press).