As someone embedded into the Tampa Bay art scenes, my admitted tendency is to frame any narrative of the late artist Theo Wujcik as a sort of punk rock hagiography. However, in his latest museum exhibition—Cantos at the Museum of Fine Arts, St. Petersburg—Wujcik becomes a proper guide of hell itself.

Following training as a master printer in New Mexico, Wujcik arrived in Tampa in 1970 to helm the University of South Florida’s Graphicstudio, where he printed for artists such as James Rosenquist, Ed Ruscha and, Richard Anuszkiewicz. Portraits of these fellow artists and friends accelerated Wujcik’s career as a printer and, importantly, as a painter. Wujcik quickly outgrew Tampa and yet remained. Before he died in 2014, he was a professor at the University of South Florida until 2003, teaching generations of students—many of whom imitated his example of forgoing the often perfunctory move to New York City and instead helped establish a now-thriving art scene in Tampa.

In the 1980s, Wujcik and his work began to take root in Ybor City, a historic neighborhood in Tampa, Florida. When the neighborhood first sprouted in the 1880s, it was largely populated by Cuban and Italian immigrants employed by a booming cigar industry. A century later, Wujcik was a member of a burgeoning arts community centered in the neighborhood, which found itself at a deep economic ebb. Then, and to a lesser degree today, the general character of Ybor City is a strange mix of the revelry of New Orleans, the giddy strangeness of San Francisco, and its own distinctive sense of violence that seems to condensate with the humidity. Wujcik and his colleagues stalked the defunct cigar factory floors and brick streets, organizing art exhibitions and punk shows.

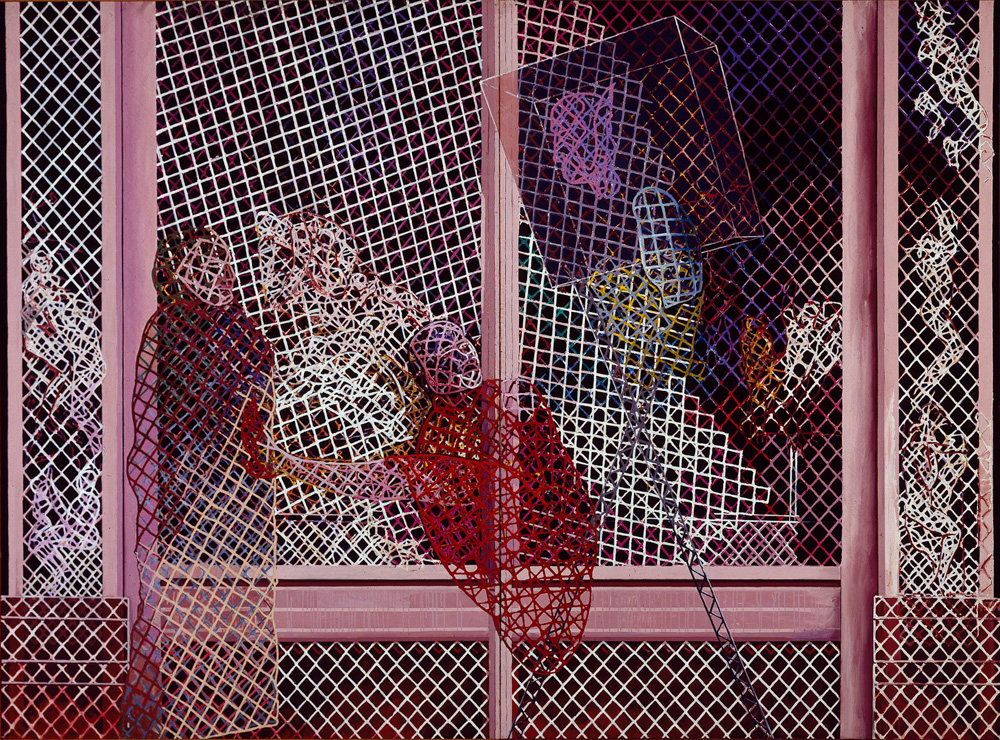

At that time, the ubiquitous brick surfaces of Ybor City were interrupted by fencing and sequestered into empty lots. It was in one of these lots that Wujcik discovered a discarded object that would catalyze a new series of work. That found object, propped in a vitrine along one wall of the exhibition at the MFA St. Petersburg, is a ragged jewelry box with the name DANTE printed in capital letters on its white satin lining. Built upon two works in the museum’s collection—Canto II (1997) and the recently acquired Gates of Hell (1987)—the exhibition highlights a series of paintings created over a ten-year period that draw on the first part of Dante Alighieri’s fourteenth century epic Divine Comedy, The Inferno.

Much of the symbolism Wujcik uses throughout the series can feel opaque, nearly impossible to parse. Despite the large-scale size of the canvases, these compositions don’t seem intended as grand revelations but personal meditations. If the visual metaphors are difficult to make out, it may be because he’s holding them so close; they feel intimate, even private when picked apart. This highly personal symbolism forcefully transforms the narrative tone of Dante’s cantos from indictment to one of frank self-reflection. This is especially well illustrated in the painting Men We Were Once (Canto XIII) (1997).

In Canto XIII of The Inferno, Dante and his guide Virgil visit the second ring of the seventh circle of hell, which contains the souls of people who attempted or committed suicide. Highly foreshortened wooden coat hangers dominate Wujcik’s painting, their corners visually protruding like bare shoulders. They recall closets as common domestic scenes of suicide and hanging as a frequent means. Beside the hangers, the painting shows a heavy red curtain representing Dante and a white dress shirt representing Virgil. Snippets of trees rendered in a comic book style are scattered along the bottom of the composition, referencing these tormented souls, who are punished by being transformed into trees and can only relate their suffering when a branch is broken off and bleeding.

As the metaphors in each painting turn inward, the hell Wujcik depicts is shown not as a site of damnation but as a psychic state. Though the paintings are formally impressive, the compositions are also surprisingly tender. In this way, as a transgressive punk patron saint of Tampa and the exhibition’s own Virgil, Wujcik descends through the circles of hell as cramped but familiar landscapes of chainlink fences, beach umbrellas, lonely closets and living rooms. In his paintings, these familiar environs may already be hell—not because this is a world of torment, but because we are each transgressors.

Theo Wujcik: Cantos is on view at the Museum of Fine Arts St. Petersburg in St. Petersburg, Florida, through June 2.