During this long, lonely, tumultuous summer, between stretches of dread and arid numbness, comic books have been my primary, most consistent source of joy and deliverance. This summer I’ve read comics about Jack the Ripper and the occult, about an interdimensional S&M warlock, about a Black journalist solving crimes in 1972 Detroit, about gods posing as rock stars. Despite my earnest efforts to do away with the high-low cultural hierarchies in my head, reading comics still provides me with a charged hit of satisfied indulgence—but no guilt, just pleasure.

Reading comic books always feels like a sort of return to me, a return to a younger version of myself, a reader with fewer preconceived notions, with an imagination less fettered by convention and experience. But comic books require a return to a different kind of reading, too: a kind of reading that is more like looking. This consideration is part of what drew me back into reading comics around five years ago, shortly after I graduated from college and began attempting to write seriously about visual art. Feeling restrained by my academic training in literature and searching for a way to freshen up my eyes for looking rather than reading, I used comics to practice how to identify and follow unfolding visual languages, how to appreciate the capaciousness of images, and, most of all, how to find pleasure and meaning in that process.

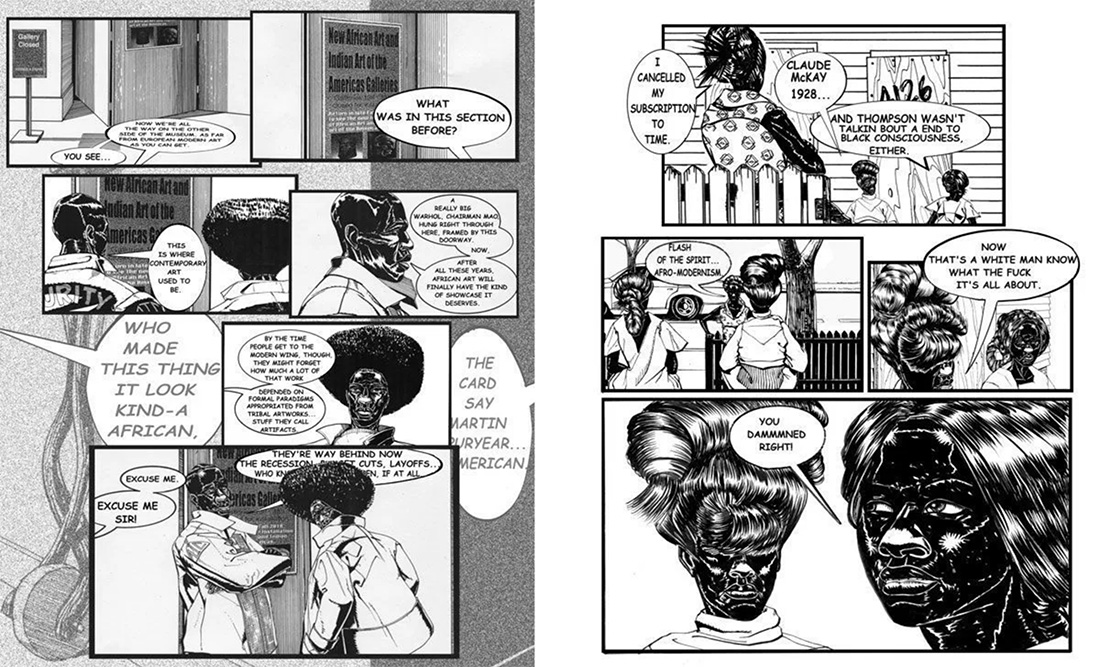

“For freewheeling cultural commentary, I cannot think of a more flexible platform than the daily newspaper comic. The loosely gridded, standard half page can accommodate an extraordinary variety of styles, subjects, and treatments,” Chicago-based artist Kerry James Marshall said in a 2014 Artforum feature. “You can hit hard or be as sensitive and silly as you like. You can be immediate and topical in ways that are less forgiving in, say, painting” [1]. While regarded as among the greatest American painters of his generation, Marshall began creating his own comics for the 1999/2000 Carnegie International in Pittsburgh. With its initial run printed as broadsides on newsprint for the installation, Marshall’s ongoing comic Rythm Mastr is a superhero story involving Yoruba gods and set in the Bronzeville neighborhood of Chicago’s South Side. The series also appeared in single panel installments in The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette’s magazine every Tuesday over the course of eight weeks during the exhibition’s run, returning the comic to the democratic print format that attracted Marshall as both a reader and an artist. Critics have often spoken in broad, facile terms about Marshall’s project to fill the absence of Black characters in comics, but the artist’s own words suggest a more nuanced understanding of the narrative and heroic possibilities available to Black superheroes and Black comics writers. “It’s one thing to create a set of muscle-bound characters wearing capes—it’s another thing to put them in context where they matter,” he wrote in Artforum in 2000. “A lot of Black superheroes just ended up fighting petty crime. So the underlying concern of my story was the legendary struggle for the souls of Black folks, to borrow a phrase from W.E.B. Du Bois” [2].

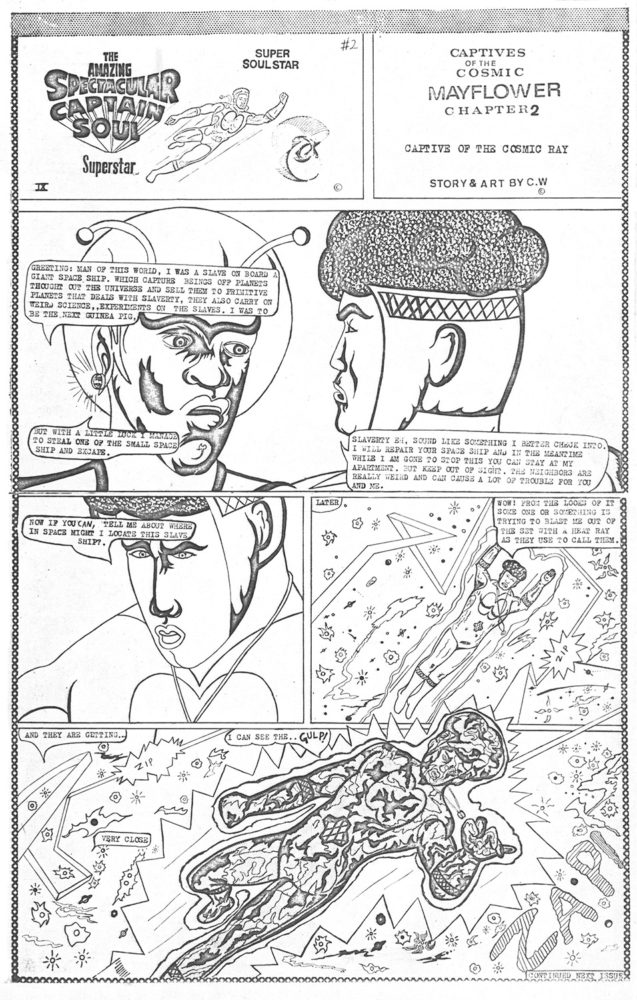

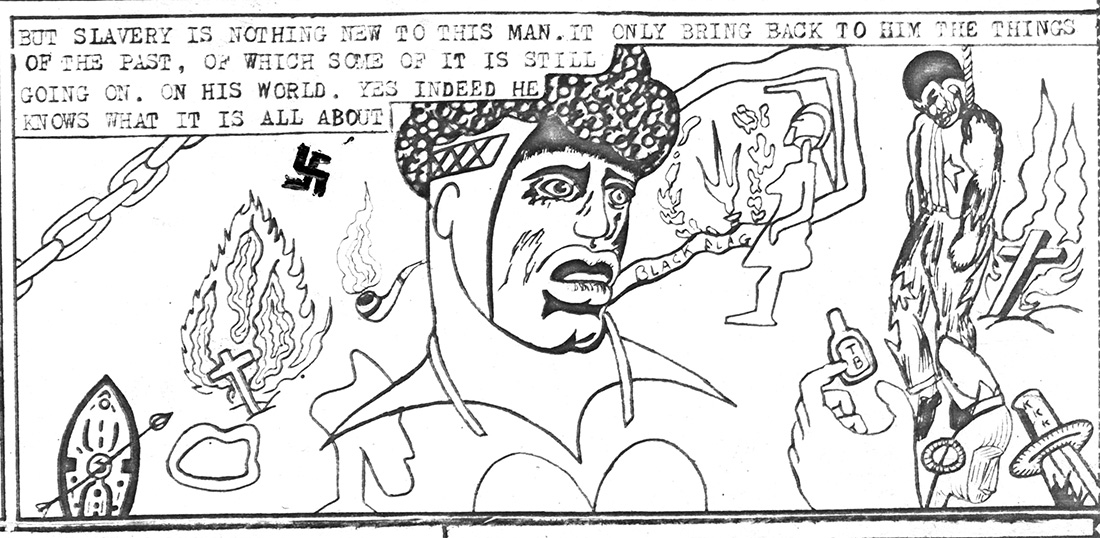

Over two decades before Marshall began working on Rythm Mastr, another artist—Charles Williams of Lexington, Kentucky—had taken on a similar endeavor in a comic of his own, The Amazing Spectacular Captain Soul. In his initial appearance, the hero is announced in a “Super Soul Special Announcement” as Bold, Black, and Beautiful. While more stylistically in line with the Space Age expressionism of Jack Kirby’s Silver Surfer than Marshall’s grittier Rythm Mastr, Williams’s comics show a Black superhero discovering the evils of racism as a sort of interstellar conspiracy. In the six-issue run “Captives of the Cosmic Mayflower,” the only known full arc of Captain Soul in existence, our hero learns of a “cosmic slave ship” called the Mayflower after meeting a recent escapee from the vessel who has crash landed on Earth. His response to the tale is almost deadpan: “Slavery, eh? Sounds like I better check out.” Yet as he meets other enslaved heroes aboard the Mayflower in the fifth issue, “The Plot That Soul Built,” a striking panel makes clear that Captain Soul is viscerally familiar with the realities of centuries of racist violence on his home planet. Against a backdrop showing burning crosses, a swastika, and chains, our hero grimaces. The text reads, “But slavery is nothing new to this man. It only brings back to him the things of the past, of which he knows some is still going on. On his world. Yes indeed he knows what it is all about.”

The six single-page issues of “Captives of the Cosmic Mayflower” are included in The Life and Death of Charles Williams, the first-ever major solo exhibition of the artist’s work, curated by Philip March Jones and on view at Atlanta Contemporary through August 2. Williams taught himself to draw as a child in rural Blue Diamond, Kentucky—a place he described as a “little old country hick town in coal mining territory… back up in the hollow where the Blacks lived”—by copying the figures of Superman, Batman, and Dick Tracy from comic books. These figures also appear in The Life and Death of Charles Williams, depicted either in paintings or in the wooden cutouts that populated the yard show he maintained in front of his home. Williams created The Amazing Spectacular Captain Soul—along with many of the other drawings, assemblages, and sculptures included in the exhibition—while working as a janitor at IBM in Lexington. Using pencils and other writing instruments gathered from the desk drawers of IBM employees afterhours, Williams created a prodigious collection of “pencil holder sculptures.” Installed in an impressive tabletop display, these sculptures appear to variously resemble fantastical creatures with protruding antennae or colorful model spaceships. The exhibition also includes a selection of panels from Cosmic Giggles, a comic Williams began in 1975, which narrates the misadventures and bemused commentary of Martians visiting Earth in the pithy, single-panel style associated with some newspaper comics. In one installment, captioned I think we better keep on pushing, a Martian spacecraft passes by Planet Earth, which is topped with an enormous sign reading BLACK POWER [3].

Courtesy Phillip March Jones and Institute 193.

In an unfortunate irony, Williams’s exhibition—like his own life—has been cut short by a mismanaged pandemic. The artist suffered a tragic, untimely death in 1998 as a result of AIDS-related complications and starvation. Later that year, the circumstances of his death led Michael Thompson and Carol Farmer to establish A Moveable Feast, an organization which has delivered over 600,000 nutritious meals to people living with HIV/AIDS in Lexington and Fayette County since its founding. A resounding note at the end of Williams’s life, the incalculable grief born of unnecessary suffering is grotesquely familiar today, perhaps especially in the United States, where the lack of sufficient timely response to COVID-19 has led to disproportionate deaths among Black Americans. As public health studies consistently report, similarly willful mismanagement has led to an undue, unequal number of Black Americans affected—like Williams—by the ongoing HIV/AIDS crisis.

We are no strangers to loss this year. Whether acknowledged or not, in a country so fundamentally mired in divisive partisan binaries, loss has become our definitive common property. After so many months spent acclimating to the required daily calculation of appropriate human suffering, some losses feel markedly unfair. At least that’s how I felt on a Friday night a few weeks ago when I learned that Representative John Lewis—the son of Alabama sharecroppers who delivered sermons to chickens as a boy, one of the thirteen original Freedom Riders, the youngest person to speak at the 1963 March on Washington, and the first member of Congress to write a comic book—had died.

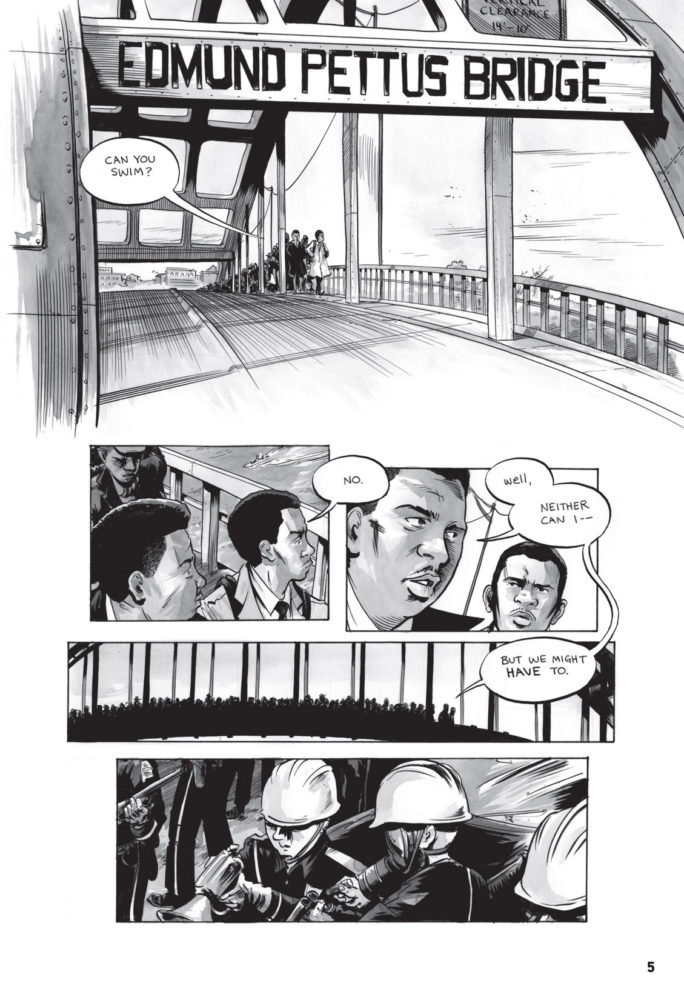

I met John Lewis once, in Nashville, at the Southern Festival of Books, where he delivered the keynote lecture celebrating the release of March: Book One in the fall of 2013. Published as a trilogy of graphic novels, March narrates Lewis’s involvement in the Civil Rights Movement, from sit-ins he attended as a student at Fisk University to the brutality he suffered on Bloody Sunday in 1965. “Thank you, Nashville,” he said at the conclusion of his lecture. “Thank you for helping me find a way to get into trouble—necessary trouble. The first time I got arrested it was in Nashville, and I felt liberated.”

Speaking about his decision to write a graphic novelization of his life, Lewis cited the influence of Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story, a sixteen-page comic book published in 1957 that he credited with clarifying the principles and practices of nonviolence to him as a young student organizer. Andrew Aydin, who served as the congressman’s digital director and policy advisor before co-authoring March with Lewis, has said of the 1957 comic: “Once he told me about it, and I connected those dots that a comic book had a meaningful impact on the early days of the Civil Rights Movement, and in particular on young people, it just seemed self-evident. If it had happened before, why couldn’t it happen again?” [4].

John Lewis—an American superhero if there ever was one—is being laid to rest today. In a final exhortation, through an essay published posthumously by The New York Times and The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Lewis says, “While my time here has now come to an end, I want you to know that in the last days and hours of my life you inspired me. You filled me with hope about the next chapter of the great American story.” I like to imagine him leaving the planet in a shiny spaceship like one of the Martians in Cosmic Giggles, perhaps passing a version of Earth like one Williams renders, capped with the raised fist of Black Power. Or maybe, instead, he’s riding in the craft shown in another Williams comic, a flying saucer with a banner trailing behind it that reads Earth has comic books.

[1] Kerry James Marshall, From “Graphic Content: Art and Animation,” Artforum, Summer 2014.

[2] Kerry James Marshall, “1000 Words,” Artforum, Summer 2000.

[3] Charles Williams: Cosmic Giggles, March 2020, published by Institute 193.

[4] Joseph Hughes, “Congressman John Lewis and Andrew Aydin Talk Inspiring the “Children of the Movement” with March, Comics Alliance, September 16, 2013.