The influence of the art market is everywhere. As of 2019, there are few places on Earth where an artist can make work unaware of its potential commercial value. But in the 1980s and 90’s– the last decade before the internet’s emergence–one could still escape along the backroads into the American South to find a wild country zone filled with eccentric people, many of whom made art. Upon discovery, their accumulated works revealed untouched Edens of personal creativity. This context is beautifully idealized in the exhibition Way Out There: The Art of Southern Backroads now on view at the High Museum. The show tells the story of three trained artists, Roger Manley, Guy Mendes, and Jonathan Williams who traversed a flourishing rural art scene on a quest to make a guidebook, “Walks to the Paradise Garden.” Presented in an inventive mix of classic works from the museum’s Folk and Self-Taught art collection, alongside documentary photographs and bold graphics of found poetry, the exhibition design reconstructs a certain spirit of the original manuscript of their travels. Folk art can often feel sanitized in a professional gallery setting; however, this show encourages viewers to imagine the weird and magical environments from which it was originally extracted.

The impetus for the guidebook Walks to the Paradise Garden, on which this exhibition is based, was Blue Highways, a bestselling 1982 travelogue by William Least Heat-Moon. The title refers to the unofficial roads marked in blue in the old-style Rand McNally Atlas. It successfully appealed to a mainstream audience and described the charming yet underappreciated culture of the American countryside. “Landsakes and tarnation, this is a book I should have written,” exclaims Williams jokingly in the preamble. This led him to talk to documentary photographers Guy Mendes and Roger Manley “about pooling our talents and adding dazzling stops along the way of Least Heat-Moon’s journey.” Although Williams’ manuscript was completed in 1992, the guidebook was finally published this year (over a decade after Jonathan Williams passed away) by Institute 193 of Lexington, Kentucky. It’s founder, Philip March Jones, is a co-curator of the exhibition, along with the High’s in-house curators Katherine Jentleson and Gregory Harris.

Like the self-taught artists he admired, Williams likened himself an independent creative who made his work from an eccentric rural outpost. Born in Asheville, North Carolina, he made remarkable inroads to the intellectual elite of his time. As a young man in the late 1940s and early 1950s, Williams carried on like any good bohemian, dropping out of Princeton University to pursue a self-study in etching, photography, and book design. He migrated easily between San Francisco, Manhattan, Chicago, and at the recommendation of Harry Callahan, landed at Black Mountain College in North Carolina in 1951. He was on home turf again, in the bible-toting, rural south, and yet surrounded by a remarkable hot bed of liberal artists and poets. While there, under the influence of teacher and poet Charles Olson, he founded what became the Jargon Society, an alternative publisher dedicated to obscure writing. For more than 40 years he continued to use this platform to publish whatever the hell he felt warranted documentation, including poetry, prose, photography, art by self-taught artists like Thornton Dial and Howard Finster, and even “White Trash Cooking” recipes. Allegedly, Williams turned down an early opportunity to publish Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl” but, he had no regrets. “If [I] had published it,” quoted The New York Times in his obituary, “it would have sold 300 copies.”

If the museum’s formal context domesticates the art on view, the book contains much of the original wildness of the self-taught artists, photographers, and poet alike. Williams writes in a raucous free-form language alongside documentary photographs by Roger Manley and Guy Mendes. Like many southerners, all three appear to share a healthy distaste for the dominance of a high brow, city-centered art world and have identified with being on the outside of that sphere. They were progressive to value the undomesticated creative genius that proliferated in the hinterlands of their home zone and all shared a prescient desire for its preservation.

The exhibition is so elegantly designed, but only briefly addresses a few complications: embedded in this story are important issues of race, economics, and power. A video at the entry addresses this briefly by quoting Williams. In hip colors and quick clever edits, it serves as a cute and yet courageous disclaimer for the entire show, claiming light-heartedly, “Okra eaters and non-okra eaters alike, don’t fret.” The video goes on to acknowledge that three southern white men made the guidebook, around which the entire show is structured. An accented voice implores the audience that the exhibition is notanthropology, nor is the book kitsch for the coffee table. In a time of contentious identity politics within the art establishment itself, the history of folk art’s discovery is somewhat fraught. It would be disingenuous to sweep this under the rug entirely. But by treating it with humor, the curators cast those issues easily aside and plunge directly into the fun.

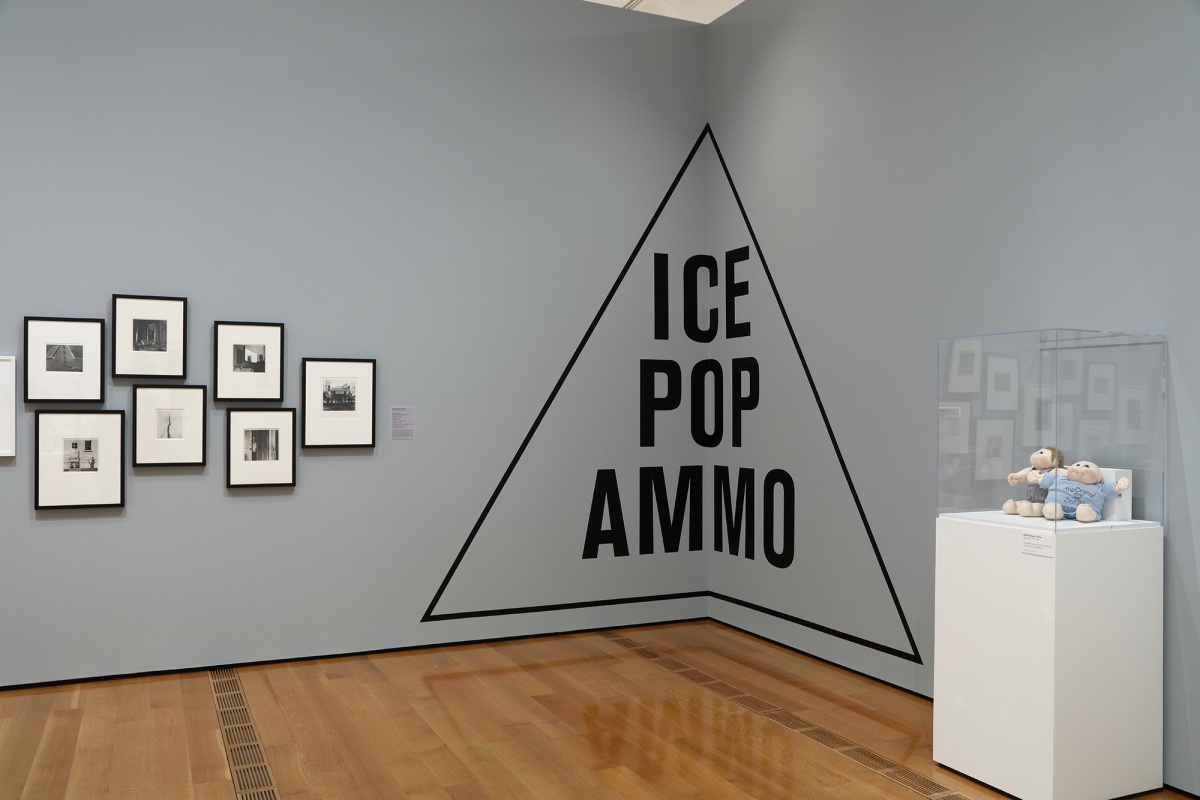

One prime example of the fun in Way Out There is the graphics. In particular, the typography really captures the nascent desktop publishing era. Graphic lists in hobo font infuse the mood with quick blasts of found words. A colorful wall shouts out the names of towns in Tennessee like “gold dust,” and “strawberry plains.” Rogue road signs appear without labels., More explicit, uncensored messages from the book like “IF YOU DON’T LIKE MY DRIVING, DIAL 1-800 EAT SHIT” are missing. Nor do we really get a taste of the many off-colored sexual jokes and profanities buried within William’s texts. For the gallery, a few select, but still awkwardly funny, mini billboards float above the art, like the one that promotes: “SPRING LIZARDS, POLISH SAUSAGE.”

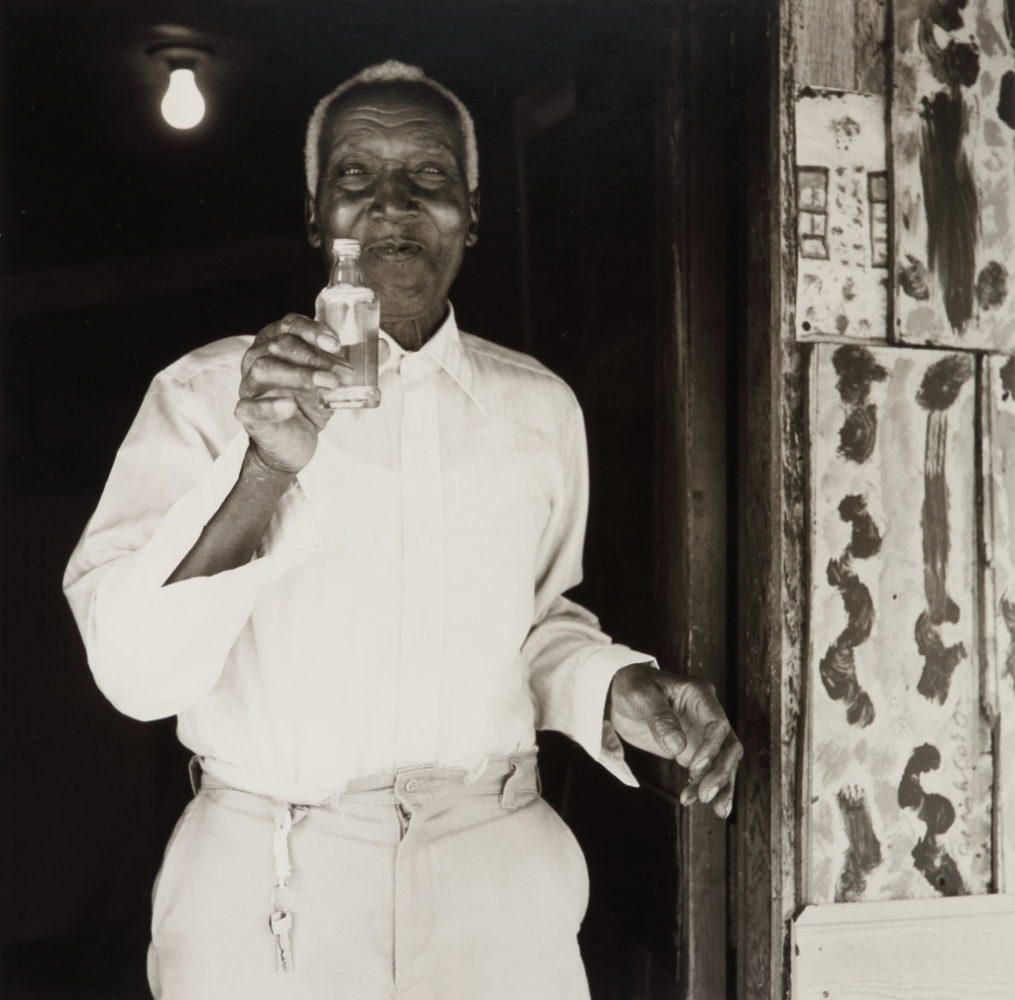

The self-taught celebrities are dutifully represented: Howard Finster, St. EOM from the Land of Pasaquan, Thornton Dial, and Lonnie Holley, but lesser known artists and anonymous found art are also present. The artists are diverse in age, race, gender, and geography, emphasizing a diversity in the rural scene that undercuts perceptions of the South’s backwards rural politic. Many lesser-known women artists of the South like Mary T. Smith, Georgia Blizzard, Minnie Links Black, and Sister Gertrude Morgan are given some real estate along with their more well-known male counterparts.

Southern self-taught art is nothing if not maximalist. The consistent horror vacui of self-taught artists is managed within many traditionally framed photographs of insanely packed art yards. Clyde Jones’ backyard army of animals made out of logs is an excellent example of an artist-initiated gallery unfurling outdoors. Manley tames what looks like hundreds of artworks into a single photograph. The book refers to this as a “yard show,” a fitting term for backroad galleries the travelers documented.

In particular I liked the work of Enoch Wickman from Tennessee, though the photographs of art attributed to him are co-creations with vandals who beheaded and amputated many of his figures. In what would be a lovely sculpture of a man with gray overalls holding a blue-frocked baby, the space where the heads should be is replaced by pink blossoms from a tree blooming in the background. In another black and white photo, two headless statues atop a plinth shake hands in the woods. The inscribed poem written by Wickman is reprinted in the book, a rather nonsensical account of civil war heroes, an execution, and dying a thousand deaths before betraying a friend. This photograph speaks uncannily to the contemporary conversation around confederate monuments happening throughout Southern cities. The images of Mendes do not editorialize and are hilariously straight. The adjoining story recounted by Williams in the book reads, “Even with no heads, with all the graffiti. Everything in America is so quickly subject to savagery and ruin. Is it the diet? Is it our collective fear?”

The work in Way Out There: The Art of Southern Backroads, and the interesting avant garde who brought it to the public’s attention, reveals a critical time capsule which will continue to be unpacked for decades. Most inspiring is how artists worked without much intention for commercial success. Reading through the book, many interviews reveal artists who are under-employed or retired. Unlike their urban counterparts they had ample time and space, and many used their art to work through boredom or personal psychological issues. This reflects a raw and honest humanity, while expressing convoluted and complicated politics unconsciously. This is where the analogy of many paradises feels most apt. A religious word for utopia, paradise is that idyllic garden, a blissful state before awareness. Like dreamy children, these artists are frozen in time, both free from and vulnerable to the savvy art world beyond. The exhibition successfully makes a case for understanding southern self-taught art within a universal rural identity. And with this message, the exhibition avoids some ugly southern baggage, opting instead for folk art’s radical accessibility for a mainstream audience. It also serves to further validate the genre to an international market hungry to consume.

Way Out There: The Art of Southern Backroads is on view at the High Museum of Art through May 19, 2019.

Walks to the Paradise Garden is now available for purchase through Institute 193.