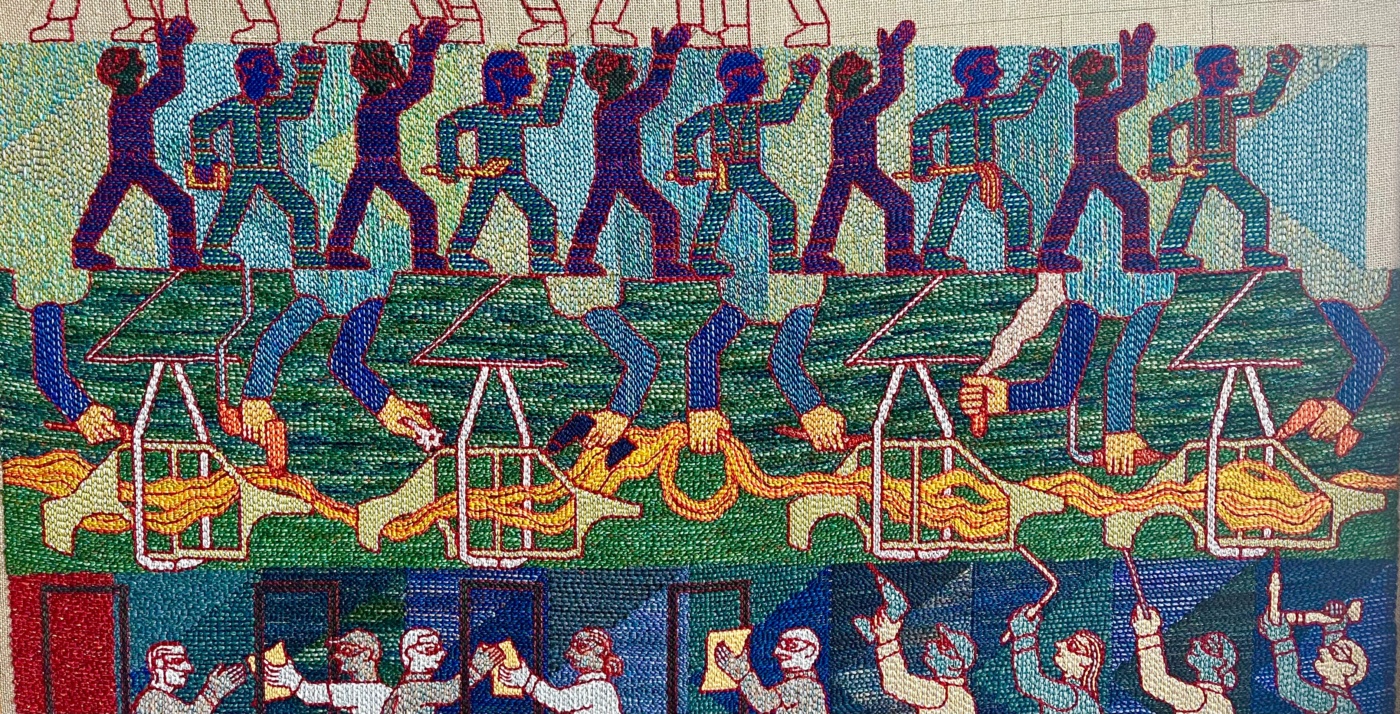

A giant red rat with its mouth agape prepares to attack, its eye a setting sun. Architectural in nature and monumental in scale, the rat houses eight working laborers in its body and a stagnant, seated boss at its head. This murine godzilla towers above an urban landscape composed of several horizontal levels that each maintain their own pattern of human and machine locomotion. In the depths of this city, a line of eight haloed workers carry a snake rightward, holding picket signs that read: “Labor is entitled to all it creates.” Close to the middle, two white airplanes fly leftward, layered over a row of townhouses. Just below the skyline, a line of green, winged angels float to the right, trumpets in hand. A factory behind them releases smoke into a cloudy, tangerine-colored atmosphere.

Legible in style but ambivalent in message, this nightmarish scene belongs to the world of fiber artist Tabitha Arnold’s punch needle tapestry Picket (2021). The rat’s name is Scabby, and union workers across the country know him most fondly as a large inflatable and a nationwide-symbol of labor conflict. Picket finds a companion in Hot Labor Summer (2023), which shares a similar composition but substitutes Scabby for Corporate Fat Cat, the beady-eyed rodent’s lesser-known companion. These tapestries are a pair. “I wanted to look at the new symbols of labor and socialism in the twenty-first century,” Arnold told me. “When I first moved to Philly as a college student, I remember seeing Scabby on the street and thought it was such a striking, effective image.” Between 2021 and 2023, the American labor movement witnessed energetic growth, with workers collectively walking off the job across the country. Arnold’s inclusion of logos from striking unions in Hot Labor Summer—the Teamsters and Temple University’s Graduate Students Association, the Writers’ Guild of America, and the United Auto Workers—reflects that insurgency.

I saw these two tapestries in late February in Swarthmore, about half an hour outside of Philadelphia. For a little over a month, Swarthmore College’s List Gallery hosted the first major solo exhibition of works by Tabitha Arnold, curated by Tess Wei. The title Workshop of the World refers both to Arnold’s diptych of the same name and industrial Philadelphia. Arnold studied painting in the city of brotherly love and lived there for almost a decade.

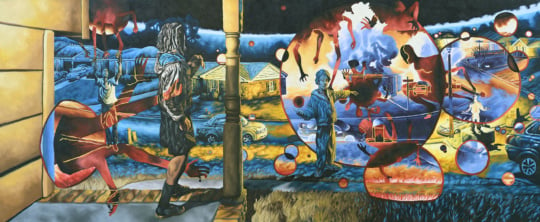

Picket and Hot Labor Summer, among other works like Time Off Task (2022), an homage to the struggle for unionization at Amazon, disclose a documentary impulse; in other words, they want to capture the prominent iconography and struggles of contemporary class conflict. But beyond realism, a particular form undergirds her tapestries, betraying an allegiance to southern artistic traditions: Christian religious imagery. Born in Chattanooga, Arnold was raised a practicing Christian. Religious imagery and narratives are, in the artist’s words, her own “default setting.” She grew up consuming biblical stories and moral allegories and today will flip through illuminated Beatus manuscripts from early medieval Spain when in need of inspiration. “In the South,” she said, “spirituality is such an intrinsic language.” The artist Howard Finster, known for his visionary artistic site Paradise Garden in Summerville, Georgia, is a key influence for the weaver. “He appropriated spiritual language or allegories to talk about all kinds of different subjects inside and outside of religion,” she explained. The same is arguably true for Arnold.

For instance, her diptych Workshop of the World (2021) is filled with fire-breathing snakes and arched, stained glass windows made of orange, red, and yellow wool and cotton yarn that brilliantly light up the ghastly ecclesiastical factory. In these two large tapestries, haloed workers pray toward the cross, read the holy word, wash clothes in buckets, and carry pots of food. At the top of the first panel sits a satanic goat balancing two red scales, with bursts of bright light shining from all its sides. In the second panel, a winged dragon bearing clocks on its back breathes billowy fire into a square factory. This is a socialist Judgment Day. “It’s a time when all the wrong-doings of the world are exposed,” Arnold explained, “there’s righteous vengeance coming to the people who’ve exploited the working class.” It’s not that Arnold believes in a Marxist God, she told me. Rather, she said, “the power of a growing labor movement could deliver that justice.”

Arnold recently moved back to Tennessee. In addition to her artistic practice, she works at a café and organizes for the Chattanooga chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), which is currently building solidarity with Palestinian liberation movements and United Auto Workers’ (UAW) unionization efforts at the local Volkswagen plant. She just finished a tapestry that narrativizes the UAW struggle at Volkswagen, which follows on the heels of UAW auto workers’ successful “Stand Up Strike” at Ford, Stellantis, and General Motors’ plants across the country. This tapestry is one of four that Arnold is producing in partnership with CALEB, a Chattanooga-based coalition of faith-based, labor, and other community organizations. Following pieces on local histories of the industrial textile strikes, the streetcar strike, and the Knights of Labor, the UAW tapestry will be the last chronologically in the series.

Despite her commitment to socialist organizing and her work with CALEB, Arnold is surprisingly hesitant about what art itself can do. For her, art is decidedly not a form of organizing, and it doesn’t directly translate to power. Art can serve as propaganda, and the process of producing it can be cathartic, a “release valve,” in her words, from life and work under capitalism. Arnold shared: “My art practice can feel disconnected from any kind of material impact, and part of that is because it’s solitary, and because I’m making fine art objects that are expensive and go into this art world ecosystem that I find pretty distasteful.”

At the same time, the fiber artist does see weaving as work. She frequently emphasizes the labor time needed to make her tapestries. In photos on her Instagram and Twitter accounts, Arnold shows her works in progress, detailing the amount of hours she’s spent on them. Hers is a “labor intensive art,” as she calls it. Arnold senses a shift in the way artists see themselves today. “When I was learning painting in an academic setting,” she reflected, “it felt very scrappy. Everyone for themselves, just trying to make it.” Since then, she has witnessed artists recognizing themselves as workers, and ultimately as a collective workforce that can organize for social change. An obvious example is the surge of unionization efforts across museums and cultural institutions over the last half decade. But she also pointed to art students at PAFA in 2020 who boycotted the annual student exhibition in light of the academy’s repressive actions against Black Lives Matter protesters.1 The boycott produced a major loss of income for the art academy. “Artists have to fight for dignity and power at work just like everyone else,” Arnold said, “I feel pretty optimistic about it.”

[1] Valentina Di Liscia, “In Protest of School’s Actions During Black Lives Matter Demonstrations, Students Boycott Annual Show,” Hyperallergic, Sept 11, 2020, https://hyperallergic.com/587502/pafa-mfa-student-grad-show-boycott/