The Artists at the Heart of Huerto Semilla

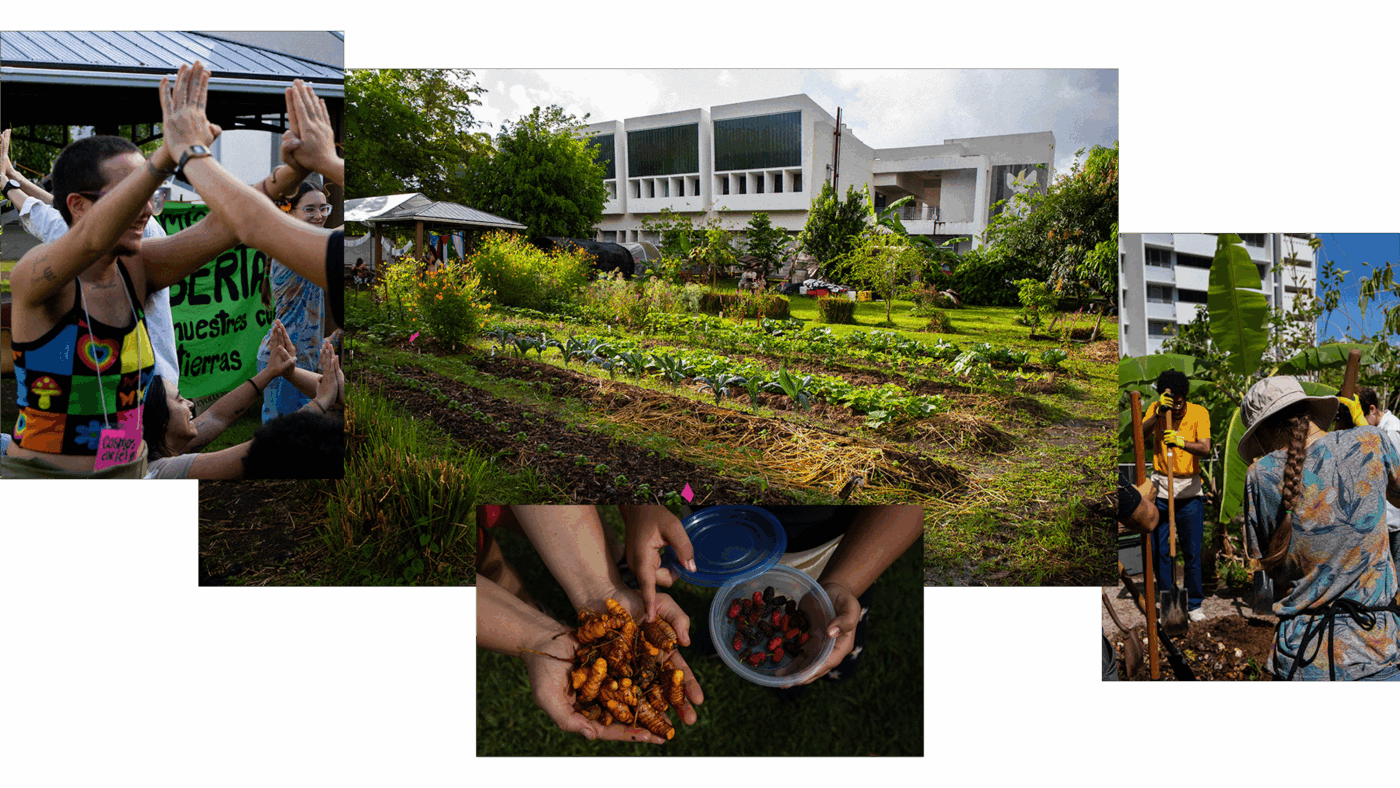

Huerto Semilla (Seed Garden) and the Escuelita Semillera, are spaces where you can dream, make mistakes, create, grieve, ask questions, find joy, and together grow a dignified present that, with curiosity and careful attention, becomes practice for the futures Puerto Rico and the wider Caribbean collectively deserve. If “the role of the artist is to make revolution irresistible,” as Toni Cade Bambara affirms, then the community of las semillas use creativity as a reminder to sink their hands back into the soil.[1] Located between buildings within the University of Puerto Rico in Río Piedras, in the archipelago of Borikén, the garden has been growing for fifteen years from the ground up, like a seed. The space is an agroecological community garden that is committed to learning by teaching and teaching by learning.[2] Members of this piece of salvaged land call themselves semillas (seeds); a transdisciplinary community of people with diverse identities, ages and interests that make up a social ecosystem of their own, with creativity and outreach at its center.

As a participatory project, the semillas do a lot with little to meet their needs as a community. They sustain and organize the space through collective effort, rooted in the purpose that with many hands and hearts, hunger can be addressed in an urban context through care towards community, land, and social justice. This is precisely why Huerto Semilla started a self-managed, free agroecology farming school, with artists at the heart of their outreach. Reconnection to the land is practiced in different ways at the garden, be it through the senses with the strong smell of compost in its process to become fertile soil, tuning into the buzzing of pollinators, and through the body, handling tools properly.[3] Much like their creative processes respectively (there are a number of creatives at Huerto Semilla), this transdisciplinary community intentionally grounds re-remembering with the sensory experience of the environment: like the first time tasting the sweet potato they harvested together, or examining precarious food systems through storytelling. By mixing science with ancestral land practices and technologies, popular education, poetry, painting, prayer, and even play, the space uses art as an expression of what moves us as human beings.

odette verónica gonzález-santiago (she/her) has been part of Huerto Semilla for twelve years. She is a nutritionist, coordinator of Escuelita Semillera, mother, and collage artist. odette’s collage practice is intertwined with Huerto Semilla and Escuelita Semillera by the shared principles of popular education, food sovereignty, and the collective processes behind food and play as part of the work. odette shares that, after moving to Orocovis with her family, a mountainous town in the center of the big island, and being far away from her community, the semilla inside her cried out.

Nutritional information isn’t usually shared through collage, but Huerto Semilla and Escuelita Semillera are spaces that practice imagination, and odette is long-time semilla. “If we’re going to teach, what methods can be invented or innovated so that it is understood? So that it’s fun and can be multiplied and shared with others? How can we enjoy the process and how do we remember this information?”[4] She shares some of the questions the semillas in the garden ask themselves when designing their curriculum, and that her own artistic practice with collage echoes. odette weaves with paper. Under her tender gaze, with each tear and cut and with glue, heeding the call of the season, she looks to generate curiosity about local, seasonal produce through poetry, colors and images in order to permeate memory with the food around us, using education and creativity to fight food insecurity.

odette’s collage project, Nutrición de temporada (Nutrition in Season), directs careful and broader attention to the diverse, nutritionally rich food that grows seasonally in the archipelago, despite displacement–which affects racialized communities the most (Hernández Báez, 2023)– and the lack of dignified labor conditions in landwork.[5] Her slow, tangible, mixed-media approach to collage serve as a gentle reminder that the whole is made up of many parts, and that it is a living process. She also includes elements that show where one might look to find that nutritious, seasonal food growing. “Sometimes in the images I connect the person who fishes with their words and efforts. Sometimes it is the tree and the fruit, the root with the leaf, with the hand or the place, if it’s by the river or the sea. I connect pieces in order to tell a story; food always comes from somewhere. I try to highlight that which gets distanced when food becomes a commodity,” shares odette. On an archipelago that imports over 85% of the food consumed, where food is more expensive due to the Jones Act, where some supermarkets in the big island might give the illusion of abundance, and fast foods spotlight many streets. Borikén – Puerto Rico is food insecure and vulnerable year-round, and this is most felt during hurricane season.[6]

In Huerto Semilla, and through their agroecology school Escuelita Semillera, there is a commitment to honor ancestral jíbaro land practices and technologies.[7] This includes examining the current food insecurity crisis, viewing disconnection with the land as inherited colonial violence, and tending to that wound with great compassion.[8] Critically asking questions around the production, processing, distribution, preparation, and consumption of food in the archipelago is necessary work to considering the future. Who does the current food system benefit, and why does colonialism intentionally sever people’s connection to the land? The answers to these questions are rooted in remembering, as people of Borikén, which can, in turn, weave the way towards reconnecting to the land in community.

Another semilla, Gabriela “Gaby Cabuya” Sánchez Deniza (she/they), is an interdisciplinary artist and an artisan of “cabuyas,” the taíno word for rope. She has been with the garden since 2022 and was one of the facilitators of Escuelita Semillera 2025. Her project, La Cabuyera, focuses on recovering and sharing textile traditions from Borikén and the Caribbean through workshops, meetings and collective creations. She learned about weaving and braiding with natural fibers from fellow artist Jorge González Santos, whose practice notably bridges the recovery of Borikua material culture through honoring indigenous and contemporary ways of living and making.[9] Gaby Cabuya first began exploring with cumbungi or cattail (Typha domingensis), and banana fibers, which she now harvests in Huerto Semilla. These self-led material learnings, and the lack of access to information on local fibers that she needed for her work, prompted Gaby Cabuya to create a botanical archive in the garden of Caribbean natural fibers for rope-making. Her practice is spiritual and political: cabuyear (to make rope) for the artist here is symbolic of weaving memory, resistance, and healing.

Who does the current food system benefit, and why does colonialism intentionally sever people’s connection to the land?

“Cabuyear isn’t just a tool, it’s also a language that helps untangle thoughts, heal memories and activate collective bonds,” she affirms. Gaby Cabuya combines her passion for education, creation, planting, and weaving in community and accompanying processes of reconnection with the land, particularly through walking the Afro-Taino Arawak red road.[10] As part of Huerto Semilla and Escuelita Semillera, she has learned to believe in herself, her community, and to trust in changing times. She shares, “Everything returns to the land, love is for all of Earth’s beings, and I belong there like the mango tree or like the zinnias on the raised beds. The garden challenges me to look at myself through the land, to learn with the breeze, to listen to the birds, to touch with the rain.”

The context that participants of the garden live and work in is representative of the wider reality of many who live in the islands. It is an archipelago that’s been colonized for over 500 years, and by the early twentieth century, 90% of its native trees were uprooted and deforested for the exploitation of sacred tobacco, sugarcane, coffee, as well as people. Locals are constantly faced with the erasure of collective memory. Organized communities like the semillas, are attempts towards sovereignty, mutual aid and solidarity. Although the present that Puerto Ricans deserve, that odette and Gaby Cabuya work toward, is practiced and workshopped in Huerto Semilla, it is not, nor does it pretend to be, perfect or utopian. The commitment is to try. With effort and care, try. This is why they plant together, compost as a group, and work with reverence and reciprocity towards the full cycle of co-creation in their efforts with the land. In the language of the landscape, strong forests thrive through a diversity of seeds. According to the community wisdom of the semillas, this means ensuring that “every person in Puerto Rico—Borikén—has access to healthy food; understands how to produce nutritious food; knows, defends, can enjoy and can sustain the territory and body we inhabit. That care is at the center of our collective life.”[11]

Les Artistas al Corazón de Huerto Semilla

Huerto Semilla y la Escuelita Semillera son espacios donde se puede soñar, errar, crear, pasar duelos, preguntar, encontrar gozo, y juntes sembrar un presente digno, que con curiosidad y atención cuidadosa, se vuelve práctica para los futuros que Puerto Rico y el gran Caribe merecemos. Si “el rol del artista es hacer que la revolución sea irresistible”, como afirma Toni Cade Bambara, entonces la comunidad semillera y las semillas que hacen su trabajo visible, utilizan el arte para recordarnos a volver a poner las manos en la tierra.[1]

Ubicado entre edificios dentro de la Universidad de Puerto Rico, recinto de Río Piedras en el archipiélago de Borikén, Huerto Semilla lleva quince años creciendo desde abajo como semilla. Es un huerto comunitario agroecológico que apuesta por enseñar aprendiendo y aprender enseñando.[2] Les integrantes de este pedazo de tierra rescatada se llaman semillas: una comunidad transdisciplinaria de personas de diversas identidades, edades e intereses, que componen un ecosistema social propio con la creatividad y el cuidado como punto de partida.

Como proyecto participativo, las semillas hacen mucho con poco para atender sus necesidades como comunidad. Elles sostienen y organizan el espacio a través del esfuerzo colectivo, enraizades en el propósito de que, con muchas manos y corazones, se puede atender el hambre en un entorno urbano, desde los cuidados en comunidad y hacia la tierra y la justicia social. Es por esto que Huerto Semilla comienza y autogestiona su programa educativo de siembra agroecológica llamado Escuelita Semillera, con artistes al corazón de su difusión. Allí se practica la reconexión con la tierra de distintas formas: ya sea a través de los sentidos con el fuerte olor de la composta en su proceso a convertirse en tierra fértil, sintonizando al zumbido de polinizadores y a través de la cuerpa, utilizando herramientas adecuadamente.[3] Al igual que sus respectivos procesos creativos (hay muchas semillas creativas en Huerto Semilla), esta comunidad transdisciplinaria intencionalmente basa el estar presente con la experiencia sensorial del entorno, como la primera vez que prueban distintas variedades de batata dulce (o camote) que cosecharon juntes o cuando examinan la precariedad de los sistemas alimentarios contando cuentos. Combinan la ciencia con saberes y tecnologías ancestrales, la educación popular, la poesía, la pintura, el rezo y hasta el juego, y utilizan el arte como expresión de todo lo que nos atraviesa y el poder que tiene de movernos.

odette verónica gonzález-santiago (ella/nosotres) es una de las semillas integrantes de Huerto Semilla desde hace doce años. Es nutricionista, coordinadora de Escuelita Semillera, madre y artista del collage. Su práctica artística del collage está intrínsecamente relacionada con Huerto Semilla y Escuelita Semillera por los principios de educación popular, la soberanía alimentaria, lo colectivo de los procesos detrás del alimento y el juego como parte del trabajo. odette cuenta que, después de mudarse con su familia a Orocovis, pueblo montañoso, ubicado en el centro de la isla grande, y al estar lejos de su comunidad, esa semilla dentro de sí, grita.

No es usual hacer collages para compartir información nutricional, pero Huerto Semilla y la Escuelita Semillera son espacios donde se practica la imaginación y odette es semilla. “Si vamos a enseñar, ¿qué método nos vamos a inventar para que se entienda, que sea divertido y que se pueda multiplicar y compartir con otras personas? ¿Cómo lo podemos disfrutar y cómo se nos puede quedar esta información?”[4], comparte odette algunas de las preguntas que las semillas se hacen mientras se diseña el currículo de Escuelita Semillera y que hacen eco en su propio trabajo artístico con el collage. odette es tejedora de papel. Bajo su mirada sensible, rasga y corta, pega y escucha el llamado de la temporada, busca generar curiosidad sobre productos locales de temporada a través de la poesía, de los colores e imágenes, con el fin de que permee en la memoria el alimento producido localmente, efectivamente utilizando su creatividad y la educación para combatir la falta de información sobre la inseguridad alimentaria.

El proyecto de collage Nutrición de temporada de odette presta atención cuidadosa y amplia sobre los alimentos diversos y nutricionalmente ricos que crecen por temporada en el archipiélago, a pesar del desplazamiento–que más afecta a comunidades racializadas (Hernández Báez, 2023)–y la falta de condiciones dignas para trabajar la tierra.[5] Su acercamiento al collage es desde la pausa tangible a través de medios mixtos, para recordarnos que los enteros están compuestos de muchas partes y que son procesos vivos. También incluye elementos que reflejan dónde se puede encontrar creciendo ese alimento nutritivo de temporada. “A veces en las imágenes conecto a quien pesca con sus palabras y sus esfuerzos, a veces es el árbol con el fruto; la raíz con la hoja, con la mano o con el lugar, ya sea con el río o con el mar. Conecto piezas para contar una historia; la comida siempre viene de algún lugar. Intento destacar aquello que toma distancia cuando la comida se vuelve una mercancía”, comparte odette. En un archipiélago que importa sobre el 85% del alimento que se consume y donde la comida es más cara debido a la Ley Jones, donde algunos supermercados en la isla grande crean la ilusión de abundancia y la comida rápida ilumina muchas calles, Borikén vive la inseguridad y vulnerabilidad alimentaria todo el año, y se siente aún más durante la época de huracanes.[6]

A través del programa agroecológico de Escuelita Semillera hay un compromiso de honrar prácticas y tecnologías jíbaras ancestrales de siembra.[7] Esto incluye examinar la crisis de inseguridad alimentaria actual, considerar la desconexión con la tierra como violencia colonial heredada, y atender esa herida con gran compasión.[8] Hacer preguntas críticas sobre la producción, distribución, preparación y consumo de alimentos en el archipiélago es una labor necesaria. ¿A quién le beneficia el sistema alimentario actual y por qué el colonialismo busca siempre quebrar la conexión de gentes con sus tierras? Las respuestas a estas preguntas se enraizan en la memoria, como habitantes de Borikén, que a su vez puede trenzar el camino hacia la reconexión con la tierra en comunidad.

Otra semilla integrante del huerto es Gabriela “Gaby Cabuya” Sánchez Deniza (ella/elle). Gaby Cabuya es artista interdisciplinaria y artesana de la cabuya, palabra taína para soga. Ella forma parte de Huerto Semilla desde 2022 y fue une de les facilitadores de Escuelita Semillera 2025.

Su proyecto, La Cabuyera, se enfoca en recuperar y compartir tradiciones textiles de Borikén y el Caribe a través de talleres, encuentros y creaciones colectivas. Gaby Cabuya aprendió del tejido con fibras junto al artista Jorge González Santos, cuya práctica rescata la cultura material borikua para tender un puente honrando las formas indígenas y modernas de crear y vivir.[9] Gaby Cabuya comenzó explorando con fibras de enea (Typha domingensis) y guineo, que ahora cosecha en Huerto Semilla. Ese aprendizaje y frente al poco acceso a información sobre fibras locales, le llevó a crear un rico archivo botánico caribeño de fibras naturales que se pueden cabuyear. Su práctica es espiritual y política: para les artistas tejer es un acto de memoria, resistencia y sanación.

¿A quién le beneficia el sistema alimentario actual y por qué el colonialismo busca siempre quebrar la conexión de gentes con sus tierras?

Ella afirma que, “cabuyear no sólo es herramienta, es también lenguaje que nos permite desenredar pensamientos, sanar memorias y activar vínculos colectivos.” Gaby Cabuya combina su pasión por educar, crear, sembrar, tejer en comunidad y acompañar procesos de reconexión con la tierra desde su caminar el sendero rojo afro-taíno arawako.[10] Como parte de Huerto Semilla y Escuelita Semillera, ha aprendido a creer en sí misma, su comunidad y confiar en los tiempos cambiantes.“Todo vuelve a la tierra, el amor es para todes sus seres y pertenezco allí como el árbol de mangó o como las zinnias en los bancos. La huerta cada día me reta a mirarme desde la tierra, a aprender con su brisa, a escuchar con sus pájaros, a tocar con la lluvia.”

El contexto en el que viven y trabajan les participantes de Huerto Semilla es representativo de la realidad que viven muches habitantes de las islas; un archipiélago colonizado por más de 500 años, donde ya para principios del siglo XX, el 90% de sus árboles nativos fueron arrancados y deforestados para la explotación de tabaco sagrado, la caña de azúcar, el café y su gente, les borikuas locales se enfrentan constantemente a la borradura de la memoria colectiva. Comunidades organizadas como las semillas son apuestas a la soberanía, al apoyo mutuo y la solidaridad. Aunque el presente que les borikuas merecen y que odette y Gaby Cabuya trabajan, se ensaya en Huerto Semilla, no es, ni pretende ser, perfecto ni utópico. La apuesta es siempre a intentarlo. Con mucho esfuerzo y cuidado, intentar. Para eso juntes, con reverencia y reciprocidad al ciclo de co-creación en su trabajo con la tierra, siembran y (se) compostan. En el lenguaje de la tierra, la diversidad de semillas hace un bosque fuerte. Desde las prácticas de la comunidad semillera, esto significa que “cada persona en Puerto Rico – Borikén tenga acceso a alimento saludable; sepa cómo producir alimentos de forma sana; conozca, defienda y pueda disfrutar y sostenerse en el territorio y cuerpx que habitamos; que los cuidados estén al centro de nuestra vida colectiva.”[11]

[1] Michael Simmons, “Toni Cade Bambara: A Woman of and for the People,” The Feminist Wire, last modified November 25, 2014, https://thefeministwire.com/2014/11/toni-cade-bambara-woman-people/.

[2] “Huerto Semilla (@huertosemilla),” Instagram. Accessed September 24, 2025. Accesado el 24 de septiembre de 2025, https://www.instagram.com/huertosemilla/.

[3] Carol E. Ramos-Gerena et al., “Squatter Care: The Social Curricula of Escuelita Semillera, an Agroecological Community Garden in San Juan, Puerto Rico,” Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition (October 1, 2024): 1, https://doi.org/10.1080/19320248.2024.2405727.

[4] Odette Verónica González-Santiago (coordinator, Escuelita Semillera), interview with author, August 29, 2025.

Odette Verónica González-Santiago (coordinadora, Escuelita Semillera), entrevista con le autore, 29 de agosto de 2025.

[5] Díaz Ramos, Tatiana. “Múltiples Los Retos De La Agricultura Para Alimentar En Tiempos De Crisis.” Centro De Periodismo Investigativo, n.d. https://periodismoinvestigativo.com/2020/05/multiples-los-retos-de-la-agricultura-para-alimentar-en-tiempos-de-crisis.

[6] AJ+ Español, “¿Por Qué Puerto Rico Importa El 85% De Su Comida? La Historia Del Control De EE.UU.,” YouTube video, April 2, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DgO7scGyv1w.

[7] The term is used to describe Borikuas from the countryside. Historically, the term has also been used as an insult to describe people with little access to formal education and to single them out from people from the city. Young Borikuas, descendents of these jíbaros, have been reclaiming the term as a way to empower themselves and assert that jíbaros are keepers of ancestral ways of tending to the land and preserving culturally relevant foods.

El término jíbaro se usa para describir a borikuas del campo. Históricamente, este término también se ha utilizado como un insulto para describir a personas del campo con poco acceso a la educación formal y distinguirles con burla de personas de la ciudad. Les jóvenes agricultores borikua, descendientes de jíbaros, hemos reclamando el término como una forma de empoderarnos y afirmar que les jíbaros son guardianes de prácticas ancestrales de cuidar la tierra y preservar alimentos culturalmente relevantes.

[8] Osman Pérez Méndez, “Seguridad Alimentaria: ‘El Hambre En Puerto Rico Es Real,’” Primera Hora, September 10, 2025, https://www.primerahora.com/noticias/puerto-rico/notas/seguridad-alimentaria-el-hambre-en-puerto-rico-es-real/.

[9] Trellis Art Fund, “Jorge González Santos,” accessed September 24, 2025, accesado el 24 de septiembre de 2025, https://www.trellisartfund.org/artists/jorge-gonzalez-santos.

[10] “Gaby Cabuya” explaining what it means to walk the Caribbean Afro-Taíno Arawak Red Road, stated in an interview: “In our Caribbean Taíno Arawak tradition this means coming back to our deepest roots with respect. Afro-Arawak is an acknowledgment that not only did Taíno and Arawaks exist here, but that there was also always connection and exchange with our African roots, even pre-colonization and exploitation. My craft and my practices have led me to recognize my ancestors, and to realize that my living grandmothers recognize ‘indios’ (Taínos) in their lineage.” Interview with author, September 18, 2025.

“Nuestra tradición caribeña Taina Arawaka se refiere a volver a nuestras raíces más profundas con respeto. Afro-arawako es un reconocimiento de que aquí no solo existían taínos y arawakos, sino que también había conexión e intercambio con las raíces africanas, incluso pre-colonización y explotación. Desde mi oficio y mis prácticas hay una conexión que me ha llevado a reconocer a mis ancestres y entender que mis abuelas también reconocen en su linaje a “indios” (taínos).” Sánchez Deniza, Gabriela. “¿Qué significa caminar el sendero rojo afro-taíno arawako?” Entrevistada por stephanie s. cortés. 18 de septiembre de 2025.

[11] Instagram, “Un rezo para esta temporada.” Accessed on September 24, 2025, Accesado el 24 de septiembre de 2025. https://www.instagram.com/p/DB97dahNvvW/?img_index=1.

References

Hernández Báez, Andrea C. “Destacan que las comunidades vulnerables y racializadas son más afectadas por la crisis climática.” Centro de Periodismo Investigativo, May 10, 2023. https://periodismoinvestigativo.com/2023/05/comunidades-racializadas-mas-afectadas-por-crisis-climatica/.

This feature was chosen from submissions to Care in Precarity, Burnaway’s first open call for Caribbean writers, in collaboration with the Caribbean Cultural Center African Diaspora Institute (CCCADI). The initiative sought to nurture writing that explores practices of care as a response to the region’s compounding precarities—from issues of climate crisis and food insecurity, to the enduring colonial structures (social and systemic) that hinder community action. In a deliberate move against the linguistic siloing of the Caribbean, a vestige of its colonial history, the selected pieces are published bilingually to better foster connectivity and sharing.

Este artículo fue seleccionado entre las propuestas recibidas para Care in Precarity, la primera convocatoria abierta de Burnaway para escritorxs caribeñxs, en colaboración con el Caribbean Cultural Center African Diaspora Institute (CCCADI). La iniciativa buscó promover la escritura que explora las prácticas de cuidado como respuesta a las crecientes precariedades de la región; desde la crisis climática y la inseguridad alimentaria hasta las persistentes estructuras coloniales (sociales y sistémicas) que obstaculizan la acción comunitaria. En una iniciativa intencional contra el aislamiento lingüístico del Caribe, vestigio de su historia colonial, las obras seleccionadas se publican bilingües para fomentar la conectividad y el intercambio.