Mike Smith has lived, taught, and photographed in and around Johnson City, Tennessee, for nearly forty years. An army brat born in Germany in 1951, Smith served in Vietnam before attending the Massachusetts College of Art, receiving his MFA from Yale, and eventually relocating to Johnson City. But East Tennessee is a part of the world where even decades of hard work and residency don’t turn a transplant into a real local, as is suggested by the title of Smith’s 2004 book, You’re Not from Around Here.

This ongoing estrangement is a condition from which Smith has profited photographically: he has managed to maintain an eye that is perpetually fresh, capable of eschewing the conspicuous tropes of the Southern idiom. During his decades in East Tennessee, he has focused on the architecture, the people, and—most complicatedly—the landscapes of this region, often isolating nuanced instants of formal grace: a field perfectly bisected by fencing, a round pond gazing up dully at a winter sky, a celestial light illuminating a gas station. He has observed and depicted the poverty and strangeness of his adopted Southern home, sometimes inviting himself into people’s shacks and houses and backyards and the front seats of their cars to photograph them. He has seen the way the presence of a barn can activate a horizon and how a corrugated metal truck-bed strewn with bullet shells might resemble the stars and stripes of an American flag. A number of these evocative studies and ongoing explorations are seen in the selections of Smith’s work currently on view in the exhibition Southbound: Photographs of and about the New South at the Halsey Institute for Contemporary Art in Charleston.

It is worth remembering, though, that the South is the South, and this is America in 2018: Smith has recently been focusing on some of the tropes—let’s call them realities—that he has more or less skirted for many years. His solo show Parting Shots was presented last year at the Reece Museum at East Tennessee State University on the occasion of Smith’s retirement from teaching at the school. In that exhibition, his photographs focused resolutely on some harsh truths: the provincialism, regionalism, nationalism, racism, misogyny, and homophobia with which our country is contending, and the violence—both latent and expressed—that energizes all that machinery. A silhouette in the form of a racist caricature has been used for target practice. A cartoon outline of a naked woman on a car door is inscribed with the words “My Little Bitch.” An isolated noose dangles against a clapboard wall. An ashen-faced man lies prone in a filthy bed, a near-spent cigarette in one hand, a stained empty coffee cup and a gun within reach of the other. The show was tough to stomach and bracing at this tumultuous moment in the history of not just the South but the broader United States.

Smith continued this difficult investigation in The Lost State of Frankland, his recent exhibition at the Tracey Morgan Gallery in Asheville, North Carolina—organized and selected, he notes, during the 2016 election cycle. Frankland was a breakaway territory, formed in 1784 by a group of counties in Western North Carolina and East Tennessee with the intention of becoming America’s fourteenth state. The territory, later dubbed the State of Franklin, was ultimately unrecognized by the U.S. government and dissolved in 1789. Smith’s choice to reference this 234-year-old secessionist aspiration in his show’s title indicates that he recognizes something of Frankland’s legacy in the psyche of the region today: an atavistic belief in the difference and autonomy of its people; a tenacious—though likely unconscious—hold on that lost moment in history that might have set them apart from the rest of the country for good. This is complicated terrain to tread, and perhaps particularly for a Yankee. There is both beauty and pain in such proud roguishness, and we see both in Smith’s images.

While he has always had a keen eye for the surreal juxtaposition, Smith recently seems to be engaging with metaphors in new ways. In his 2014 photograph Elizabethton, TN, a banal roadside landscape is cut into parts by a wooden sign-frame in the foreground; one of its segments holds a photograph of a smiling, white family of four, promoting some version of the American dream. But in an ominous twist, the family portrait has been turned upside-down: this particular fantasy upended. In Weber City, VA (2016), we encounter what Smith describes as “a disturbing mix”: the bust of a plastic lamb—time-honored signifier of innocence, sweetness, the Lamb of God—sits beside the decomposing head of a deer with green twine tied daintily around its antlers. Through a window behind them we can make out the shape of a wire hanger. In this photograph, violence hangs in the air like a noxious odor.

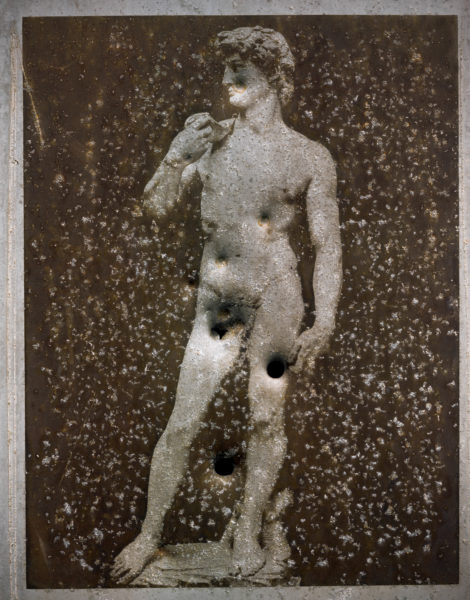

A 2010 image titled Erwin, TN enfolds multiple layers. It is a photograph of a bullet-riddled photograph of Michelangelo’s David. Smith’s print is a massive 60 by 80 inches—making David’s nude figure nearly human-scale—but the actual object documented by Smith was the size of a postcard: a discarded tin press-plate from a long-defunct printing house in Kingsport, Tennessee, used by an employee to cover a small hole in his barn. (“Not an uncommon practice in the surrounding area,” notes Smith in an email exchange: “Free tin siding.”) In the enlarged image, the bullet holes become fist-sized, puncturing David’s halftone body and notably obliterating his genitals. Smith sees in this image “a shocking affront to the history of art, the expression of hateful intolerance, and a symbol of abject ignorance.” It is a commanding and disquieting photograph that will not be ignored.

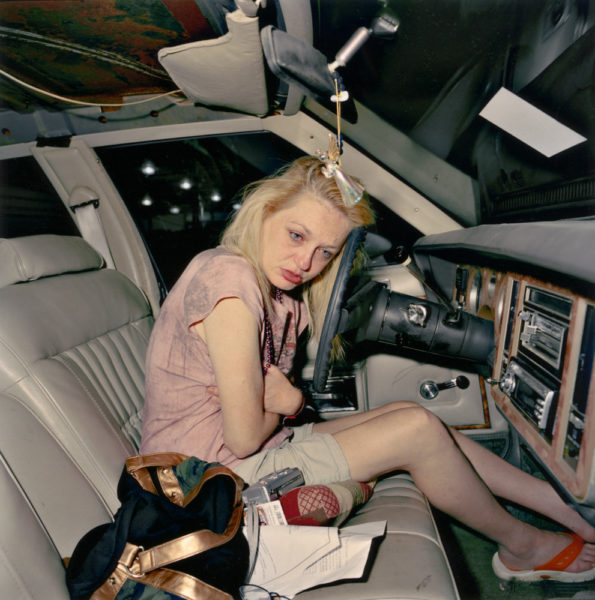

One of Smith’s strengths as a photographer—and as a person—is his ability to engage other people with a frankness that elicits frankness in return. This gift allows him to enter worlds that would likely be closed to others, and to create portraits that are almost astonishing in their candor. Among these is a series Smith has made inside people’s cars by staking himself out at a local gas station—with the station-owner’s permission—and approaching his potential subjects carefully, often breaking the ice and gaining their trust by complimenting their flatbed truck or their hound dog. One of these portraits, the 2007 image Piney Flats, TN, presents a dazed woman of uncertain age, hunched behind the wheel of a car and clutching her own torso. She has evidently been undone in some way—by drugs or drink or abuse—and even in this confined space she stares not at the photographer, who must be only inches from her, but into some foggy middle distance. This, too, is an image that is hard to look at but even more difficult to turn away from.

Smith’s own forthright presence is met and fully matched by the face of a little girl, perhaps eight or nine years old, in his extraordinary 2009 photograph titled Carter County, TN. Settled in an oversized tattered armchair in a squalid interior, she gazes directly into his lens with uncanny self-possession. Her legs are tucked partially beneath her, and in this 30-by-40-inch print we can clearly see that her shins are pock-marked and red with pustules, perhaps flea bites—and yet she leans on the arm of the chair with the aplomb of a monarch. In this image, Smith seems to have transcended the ugly politics and festering resentments and prejudices that have been on his mind in recent years, instead showing us an electric moment of human connection.

In the scheme of any concerned documentarian’s career, they will be faced at some point with this dilemma: the present or the eternal? In Smith’s body of work, this dichotomy takes specific form: the animosities that are galvanizing our moment versus the undying spirit of place and humanity. While Smith is a photographer who has the artistry and the intelligence to take on all these things, it is, of course, the latter that endures.

Mike Smith’s exhibition The Lost State of Frankland was presented at the Tracey Morgan Gallery, Asheville, NC, September 28–November 3, 2018. “Parting Shots” was presented at the Reece Museum, East Tennessee State University, Johnson City, TN, December 20, 2016–January 25, 2017. A selection of Smith’s work is featured in the group show Southbound: Photographs of and about the New South, curated by Mark Sloan and Mark Long, on view through March 2, 2019, at the Halsey Institute of Contemporary Art and the City Gallery at Waterfront Park in Charleston, SC, and subsequently traveling to multiple venues.