Giza-based artist Ibrahim Ahmed’s first major solo exhibition, It Will Always Come Back to You opened at the VCU Institute for Contemporary Art in Richmond on July 23, a week before the United States’ ham-fisted withdrawal from Afghanistan. Then, over eight days in mid-September, the Biden administration cruelly deported nearly 4,000 Haitian refugees at the U.S.-Mexico border. Global crises cast an unforgiving light on the typically passive practice of looking at art, and for better and for worse, It Will Always Come Back to You invokes what Paul Chan called “the terror of action and inaction” in his artist statement for Waiting for Godot in New Orleans (2007).

VCU’s ICA sits gleaming at the edge of downtown Richmond, addressing its surrounding, humdrum corners like an aircraft carrier marooned in a sea of parking lots. The intersection of Broad and Belvidere, where the picturesque Fan neighborhood (home to VCU’s campus and Monument Avenue) continues to radiate gentrification into surrounding neighborhoods with more working class and Black residents, is one of the most socially, politically and economically charged intersections in the city.

I was reminded of this when I went to see It Will Always Come Back to You. Approaching the ICA from the back of the building, I read the phrase “FUCK TEAR GAS” scrawled in white correction pen on the black arrow of a one-way sign. In the summer of 2020, the area around the ICA was Ground Zero for weeks of discord between protesters and the Richmond police, days that repeatedly ended with tear gas, flash grenades, and mass arrests.

The hand-written text served as a provisional caption to the nearby installation of Ahmed’s Only Dreamers Leave (2016), a series of thirty piecemeal “sails” made from scraps of fabric. Installed on metal poles rising out of the ICA’s reflecting pool, the sails periodically whipped in the breeze with the wild synchronicity only nature can score. In their modest origins as salvage, the sails call to mind the economy and imagination of children’s fantasies. Activated by gusts of wind, their violent flapping also evokes a terrifying vulnerability to the elements, reorienting the viewer’s attention to the journeys of those who cross bodies of water in provisional vessels, particularly migrants from north Africa and the Middle East crossing the Mediterranean as they flee famine and war.

Nobody Knows Anything About Them (2021) is an assemblage of chair limbs gathered from Cairo rooftops, where, according to wall texts, Cairenes have developed a practice of hoarding salvage such as broken furniture as a response to enduring decades of economic instability. Arms, legs, and backs amass into a skeletal form reminiscent of the geometric structure of an uncut gemstone (Nari Ward’s 2008 site specific sculpture Diamond Gym came to mind). Gallery texts identify Nobody… as a “chandelier,” but to describe the work this way far undersells its pathos. Nobody… is more likely to be encountered as a cadaverous pendulum, held at a standstill, bound together by furniture brads and collective dread. It hangs frozen, inches off the floor, in a manner that suggests: Dig here. Imposing and see-through, lumbering and rickety, it functions as an obstacle to be mindfully circumnavigated, like the boulders hidden beneath the surging fall line of the James River a few blocks away.

Five mixed media abstractions from the series Ard El Lewa (2016) feel the most familiar and collectible of the works on view. Works in the series obliquely reference diverse architectural and decorative motifs found along the Silk Road, a network of trade routes connecting China and the Far East with the Middle East and Roman Empire. The assemblages justifiably call to mind the sturdy funk of a Rauschenberg Combine and Mark Bradford’s “threaded text” excoriation of paint—all of Ahmed’s works are, above all, formally stellar—but eschew those artists’ references to contemporary vernacular culture. Named after the artist’s neighborhood in Giza, the works shun recognizable signifiers of place, such as landscape, scale, perspective or figures, in favor of intense, chalky earth tones, ornamentation, and surface. Throughout the exhibition, Ahmed’s mixed media surfaces reflect a painter’s sensibility for infinite degrees of tenderness and discontent. In incision, abrasion, and repair, the painted surfaces feel both precious and abused, neglected and recovered. Up close, they flood the senses, capturing the most elegant aspects of patina and weathering in places that endure. But beyond arm’s length, this exquisite messiness never challenges the flattening coherence of tasteful composition and filigreed contours.

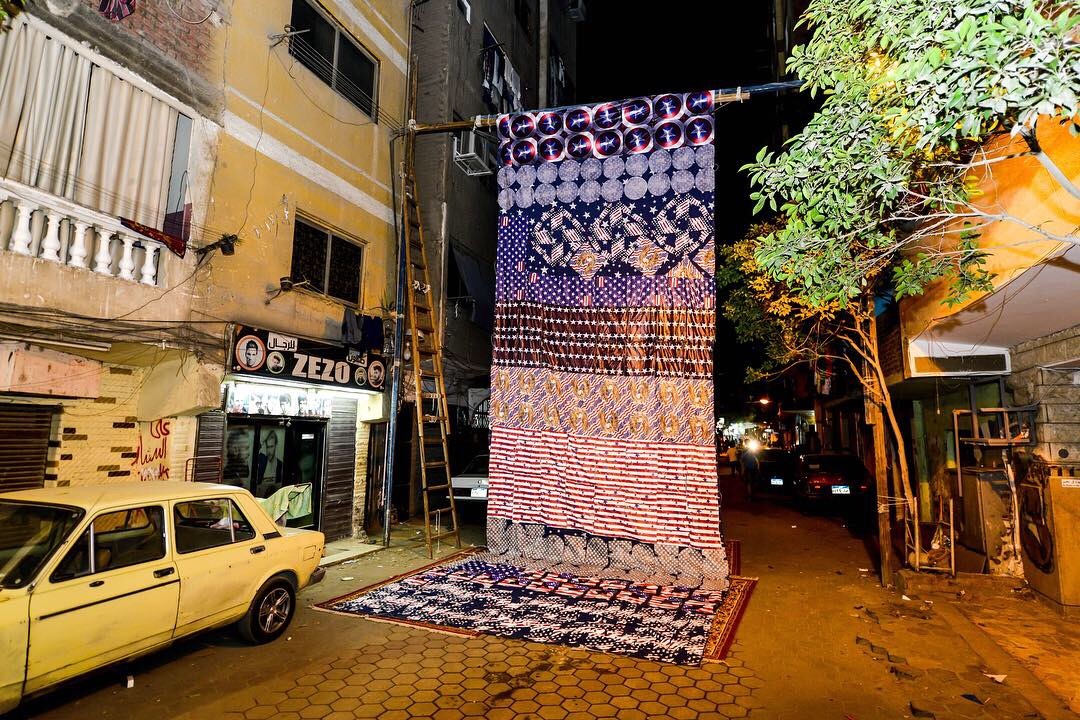

Ahmed’s works are most effective when he’s exploring the edge of his own capacities, and the scale of the project eludes his command of the materials, as in Only Dreamers Leave. One of the most affecting works in the exhibit is the imposing Does Anybody Leave Heaven? (2019). Dominating the foyer, the work is a cold-blooded parody of American influence. A monumental ersatz tapestry falls two stories from construction scaffolding and spreads across the floor like a giant wedding dress train. While the scale and installation invoke the (il)logic of fascist pageantry, the tapestry itself is a patchwork of textiles culled from Egyptian markets all bearing elements of the American flag. Each sample remixes the core components—red, white and blue; stripes and stars (alone and in fields). Captain America’s shield is clearly identifiable at the top, reminding us that the cinema arts have been one primary vector of pro-U.S. propaganda. On the floor, where the piece unfurls at the foot of the viewer, the tapestry is patched with star-studded pants, sized for small children.

It’s possible that Does Anybody Leave Heaven? could be read as its own “’Murica!”-style tribute, but the scale, and the way it spills across the floor, feels damning, like a docket or ledger of American expansion, intervention, and dalliance. The piece was originally created for the 2019 Havana Biennial and was subsequently censored. Biennial organizers claimed they could not present work that seemed critical of the U.S. A straightforward presentation of photographs and a display case run the length of an adjacent wall. The case contains clothes and accessories sourced from the same markets as those used in Does Anybody Leave Heaven? The photos are Ahmed’s documentation of his encounters with American flag paraphernalia in Havana—a starry sock, a tank top, air fresheners bearing an impression of the flag—and belie the sketchy, Acconci-esque, creeper vibe of a private investigator catching a cheater in the act. One photo shows a Confederate flag draped across the railing of a small balcony. Perhaps nothing captures Ahmed’s sensitivity to the stubborn persistence and transit of symbols like a postcard photo of the quintessential symbol of white supremacy, seen by an Egyptian artist in an authoritarian Caribbean country, displayed in the former capital of the Confederacy 160 years after its creation.

Those of us with the fortune and privilege to spend our days crafting (or writing about, or exhibiting) discreet commodity objects need to sort through our complicity and implication within systems that distribute suffering inequitably. The project of making contemporary art exhibition less alienating is long, fraught, and necessary, and maybe impossible. For now, perhaps the best we can hope for is exhibitions that are as effortlessly “place-ly” as they are timely. In a few pulsing moments, It Will Always Come Back to You reimagines the ICA site—not as a citadel of free expression or democracy, but as a fragile vessel of contingent power relations, in a city that is still navigating its own legacies of terror and fugitivity.

When art that addresses social upheaval and precarity is described as “timely,” it’s a double-edged sword: while such works cut with an immediacy that feels urgent and spectral, it also means that the conditions that inspired the work persist. One of the many challenges facing exhibiting institutions today is how they can become incubators of inclusion and belonging, even as they must service their own debts to the historically exclusionary world of fine art circulation and patronage. This perhaps includes University-affiliated institutes of contemporary art with spaces named after prominent area collectors.

Shimmering and shaped like the tip of a spear, VCU’s ICA is a manifestation of the kinds of social influence and affluence associated with rises in property value and cost of living within the very neighborhoods it occupies—which is exactly its desired function outside the art world. Exhibited in this context, even powerful work by clear-eyed artists feels parasitically dependent on the systems it ostensibly critiques. To paraphrase Baldwin: it’s easier to cry than to change.

Ibrahim Ahmed: It Will Always Come Back to You is on view at ICA VCU through November 7.