In this season’s opening exhibition at Bad Water, As for me, I’m just passing through this planet, curator Kelsie Conley delicately balanced works from Jacob Jackmauh, Caitlin McCann, and Benjamin Stallings—three artists who together create a temporary shared universe of yawning sentimentality.

The white barnwood walls of the gallery, romantically uneven and interspersed with bracing and reinforcement added over time, provide shelter to five sculptural works alongside a poetry publication. Jackmauh and McCann’s sculptures suggest a shared history, a hypnotic fiction which is stabilized in part by the atmospheric similarities between the myriad found objects in the barn. To the imaginative viewer, the oxidized patina on the briefcase hardware of McCann’s Folk Song Machine IV (2024) might suggest a shared origin to the aged fiberglass form of Jackmauh’s Seeing the Elephant (2024). Floating underneath these superficial similarities, the substantive bridge which connects these distinct approaches to sculpture is found in the silence within the works and the emphasis placed on cultural and community identity.

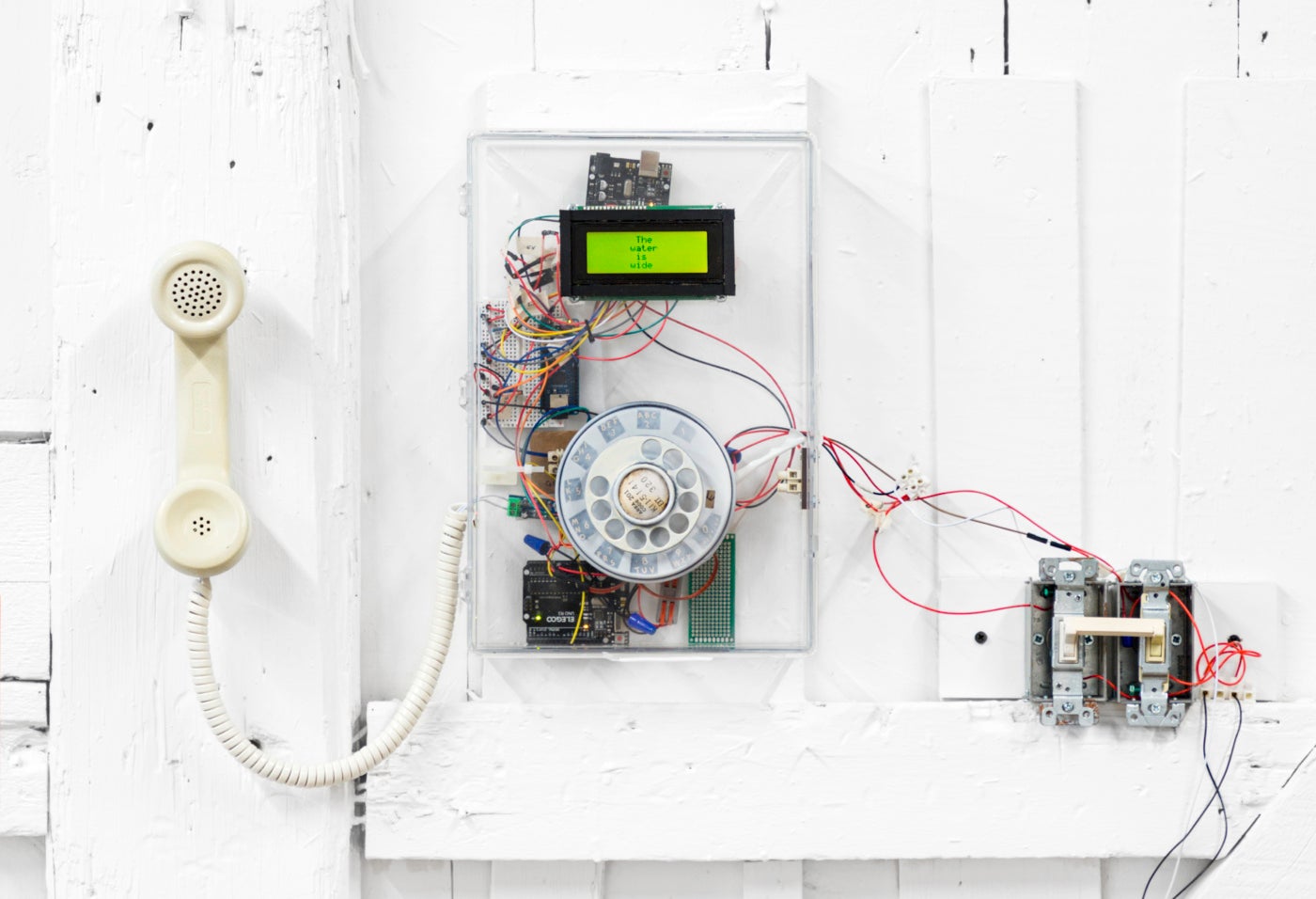

To experience Folk Song Machine IV as a static object without activating the single-pole switch which brings it to life, the bundled electronics within the well-worn briefcase evoke an emotional response which oscillates between terror and sadness. The machine’s silence is made uneasy and thick by the exposed power switch, connected by trailing wires back to the briefcase. While the work might ostensibly resemble an improvised explosive device as it lies dormant on the barn’s stage—by flicking the switch and calling the machine to its purpose, something of an implosion happens. The percussive and electronic components of the sculpture begin to perform a traditional gospel song so old that a specific author cannot be confidently identified, rendering the composition a shared cultural heirloom. The sound modules produce melodic, distilled beeps which bring to mind the sounds of a life-support machine, the snapping metal servos click in a distinctly mechanical register. While the tune of the machine is lively in its cadence, the impact of the sounds is emotionally tinted. The composition as a found material is not merely presented here but affected drastically by the hand of the artist in the construction of the instrument itself. The purpose-built, simple electronics allow McCann to add her own confident voice to the longstanding dialogue of American folk traditions. The choice to allow viewers agency in deciding when each machine on display is turned on or off creates an unexpected emotional entanglement. Turning off the machines as they eagerly share their songs is a decision that carries weight.

Jackmauh’s hanging fiberglass molds confront the viewer from every interior face of the barn. Their silence is made palpable not only in contrast to McCann’s machines, which provide a disquieting soundtrack, but also through the accumulated history that radiates outwards from each surface. Industrial molds now covered in lichen and moss colonies push viewers to reckon not only with the age and hidden history of the found objects, but also with their obsolescence as tools for commercial fabrication. The cartoonishly exaggerated features of Seeing the Elephant might have once been used in the production of a vibrant, playful statue, perhaps even a playground feature. Subtly but to great effect, Jackmauh has hung the elephant’s life-size profile high enough to confront the viewer eye-to-eye. Locked rigidly to the wall, towering over viewers with an imposing silent presence, the discarded mold has become a taxidermy specimen of somehow-American culture.

Deep inside the barn, Jackmauh’s Dividend (2024) confronts the viewer with a final silent stare. The unyielding hollow face exerts a gravity similar to that of McCann’s exposed power switches, drawing viewers into the mask tantalizingly close to the dormant wasp nest within. Similarly to his elephant, Dividend (2024) confronts viewers eye-to-eye. To experience a close-up encounter with Dividend as McCann’s neighboring Folk Song Machine III (2024) plays its raspy compressed tune is an emotional crescendo.

Benjamin Stallings’ Museum Garden (2024) utilizes forms of experimental prose and poetry to flesh out the competing feelings of decay and preservation that pervade the barn. Across three chapters, Stallings explores memories, impressions, and landscapes of the American South. In Old Car City, describing the poet T.S. Eliot, Stallings plots a beautiful intersection point for all three artists on display at Bad Water, “The poet is walking through the mess he’s made, that history’s made, and understood that he is guilty too. He is walking through the wreckage, looking for what can be saved, what’s salvageable in the after.”

As for me, I’m just passing through this planet is on view at Bad Water by appointment until April 14, 2024.