Edward Hicks painted The Peaceable Kingdom sixty-two times between 1818 and 1849. The first major exhibition of Hicks’s work was panned by the press who found his compositions repetitive—but that was the point. A Quaker minister and folk painter, he was best known for bucolic representations of the Messianic Age painted in a charmingly wonky realism and depicting lions, lambs, leopards, kids, and company laying together in harmony.

The Messianic Age, as the name might suggest, imagines a world saved by a messiah and transformed into a place where only peace and freedom are possible. Shared across the holy texts of all Abrahamic religious sects and generations of cultural imaginations, the prophecy of the messiah has contributed to a culture dependent on hope for a utopic future, waiting for a savior to deal with all the problems we willfully ignore. “If I can just get through this week, this month, this year, this life—then, I will finally be free.” But the belief in an idyllic, hopeful future in the year 2021 feels laughable at best, and more likely a delusional suspension of reality. Ground down into a human-shaped pulp as we are, how might we begin to imagine happiness and fulfilment, to grapple with a project of rebuilding a world that is neither escapist nor unimaginable?

Perhaps one of the ways to create love, meaning, resilience, and care is by making a handful of tired, begrudging decisions to show up—in spite of deadlines, burnout, anxiety, laziness, state violence—for the function. At least, this is where my admiration of the practice of Dianna Settles begins.

“We grew up very poor, I remember living in the back of my mom’s Toyota Tercel while she was pregnant with my sister, but we moved around quite a bit before winding up in Blue Ridge, Georgia. My sister and I were almost always doing something outside,” Settles tells me during a two-hour conversation in her studio in the late, sticky Georgia summer.

Her solo exhibition at Institute 193 in Lexington, Kentucky, has just closed, and she’s still deeply in the work, in love with the making of it, one year into getting her first art studio at the age of thirty-one. Settles has always been actively creating things and organizing around art, however. Since 2016, she has run Hi-Lo Press, an ambitious and beloved DIY space in Atlanta, Georgia, which has hosted exhibitions, workshops, screenings, and parties. Despite losing its brick-and-mortar space in December of 2020 when a developer bought the entire ramshackle block for a couple million, Hi-Lo has managed to continue drawing a loyal following, which has only grown as Settles has hosted pandemic-friendly, outdoor exhibitions and happenings throughout Atlanta over the past year. Between working restaurant shifts to fund Hi-Lo in its beginnings, Settles has tattooed for money and pleasure, painted murals, and made prints and publications when time permits. She has built Hi-Lo into the fulcrum on which the extended community of young, emerging artists in Atlanta turn, and she still has found time to develop a generative and ambitious art practice of her own.

Settles was born in 1989 and as a child, she drew and drew. After a stop-and-start undergraduate education at Georgia State University, she finished her bachelor’s degree at San Francisco Art Institute in 2014, spending the better part of her time in the Bay Area making monochromatic, traditional limestone lithographic prints. She took one painting class and hated it, eventually convincing her professor to let her make prints, textiles, and anything but painting.

Upon graduation, Settles traveled to Vietnam, where her father is from, and discovered the amazing way in which contemporary Vietnamese artists hybridized the restrained, flattened aesthetic of traditional Asian painting with the exuberance and loose figuration of Western modernism. The result was both strange and beautiful to Settles and has formed the basis on which she’s created paintings, drawings, and prints ever since.

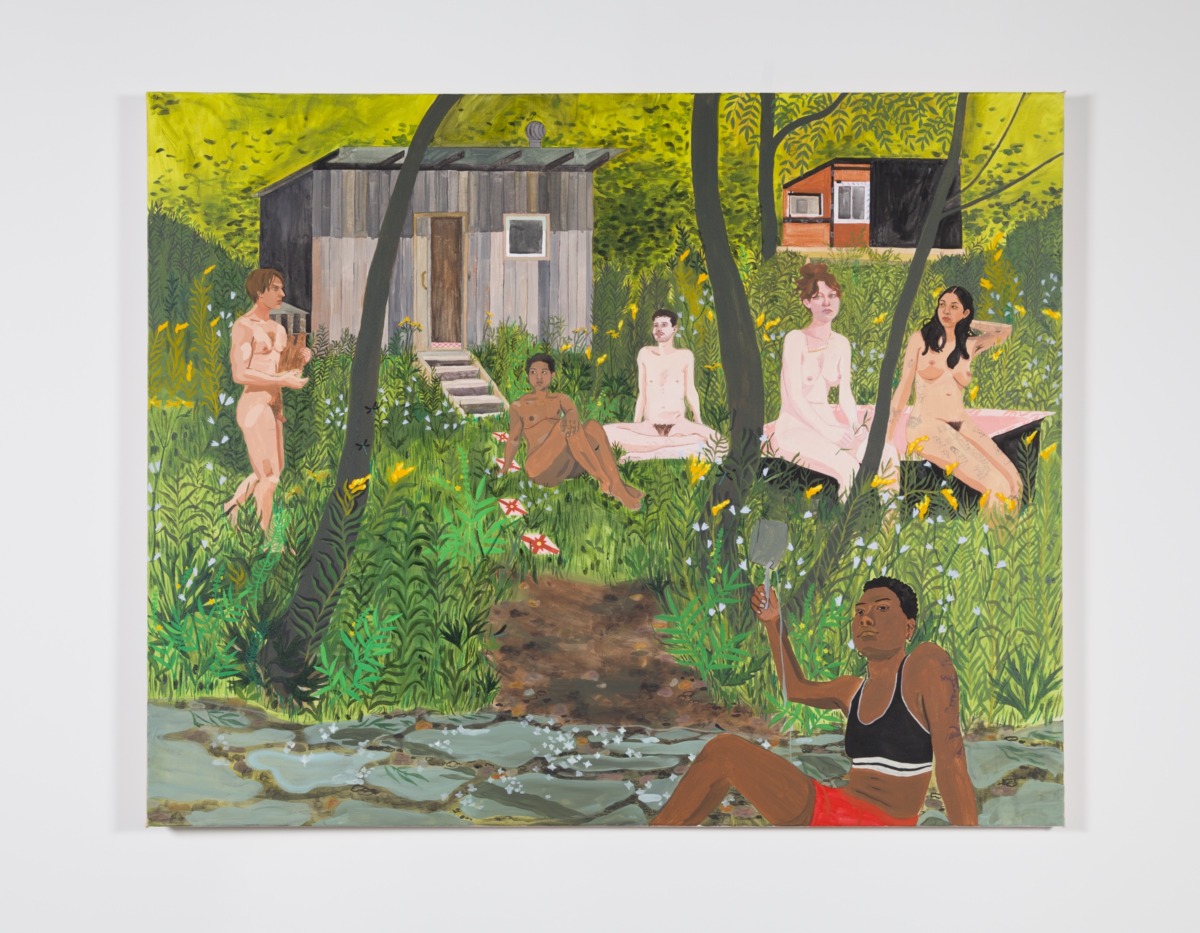

Settles primarily, almost exclusively, paints people, often in small groups engaged in an activity that can be simultaneously violent and tender, playful but physical, leisurely yet radical. The figures in her work are modeled after her own friends, painted from memory—each person is a carefully articulated portrait, distinct individuals defined by the specific tattoos on their arms, with books of poetry in their laps. In Settles’s work, they are getting arrested at protests, bathing in Korean spas, practicing martial arts, catching snakes, and processing deer in a backyard. The paintings are colorful, often pastoral, compositions that recall Edward Hicks’s peaceable kingdom both in composition and in their folky, warped-realistic style. In Settles’s case, the peaceable kingdom is reimagined in the form of people gathering after the daily battering of shift work, landlords, and the ongoing precarity that seems to define her generation.

Settles’s correspondence to Hicks is perhaps most apparent in a large work from 2021 titled To become destructed angels And as destructed open to all activities against the law and financial institutions (the fireflies are waiting). This painting does not deliver a devotional scene, but instead reclaims the parable of fallen angels and the Edenic composition of many historical religious paintings to make the case for comradery as an antidote to late-stage capitalism. Having no belief in the false promise of a messianic future, the individuals depicted have—as the title suggests—rejected the moralism of hard work and obedience in favor of their own rest and pleasure. The six mostly nude figures scatter along the side of a brook, appearing generally to be doing nothing but passing the time. Their nudity is not sexualized, and their stoic expressions do not exactly signal euphoria; the totalizing effect of the image is one of calm, loving engagement with nature. Just as Hicks’s weirded lion and leopard and cherubs scatter along the side of a hill, Settles’s friends are fully in sync with the highly articulated weeds and wildflowers that host their meeting. Light, proportion, and depth are not meant to be illusionistic, but rather to give an inventory of important details from Settles’s memory of the moment.

Like Settles in her early years, I tend to be ambivalent about painting as a medium, and especially towards figurative painting as a hegemony that has owned art for too long. How, after centuries of innovation and art history, are paintings of people still at both the apex of the contemporary art market and the pinnacle of cultural interest: the Obama portraits for example, or the Amoako Boafo painting that Jeff Bezos is taking to space?

This skepticism is swirling in the back of my mind as I ask Settles probing questions about other artists that she admires, her feelings about her recent success showing with galleries—a leading invitation to comment on her influences and her encounters with the art market and its insatiable hunger for painting. She responds with her own ambivalence, “I always feel inspired by the things that my friends and their friends are doing.” She also cites poetry, particularly that of her friends, and Diane di Prima’s Revolutionary Letters as being formative. This practice, Settles seems to declare, is of and for the collaborative, local, scrappy community that sustains her. The specters of career, popularity, social climbing, and commercial success do not haunt her. In fact, they barely even register on her radar.

What does register are the kind of strange, idiosyncratic crumbs of memory that accompany any deeply impactful communal experience. This is how Settles builds her compositions. While she might have an idea of a scene she’d like to memorialize in paint, the structure of the image is built around the handful of details that have stuck in her mind: a blanket’s pattern, the flower currently in bloom, a book strewn on the floor. Although she has painted singular portraits, the majority of her recent work depicts tangled scenes of people being present with each other or engaged in a group activity. They are scenes of communion, the vignettes with which Settles builds a new world out of the small transcendence of everyday survival.

This is not to say that she has a purely utopian or rosy vision of the world or the conditions in which her community lives—the peaceable kingdom of her paintings is not speculative, unattainable space, but rather a depiction of the positive moments or the occasional flicker of utopia that exist already, inside and alongside the challenges of daily life.

After being asked repeatedly about the radicality of leisure and pleasure in her work, Settles pushes back: “The world depicted is this one we are all living in now, which is fragmenting and toxic, being exploited and depleted at every turn—the people depicted are traumatized. They default to a state of deep misery but are still making a point to choose life and pursue pleasure and deeper friendships and connections to their environments in spite of it.”

Why would I need anything else, when all I have is all of you?

This profile was originally printed in our 2021 Reader, Treasure. You can order a copy of Treasure on our webstore.

Burnaway will be exhibiting Dianna Settles at NADA Miami, from December 1 – 4.

This essay is part of Burnaway’s yearlong series Belief and Fiction.

Find out more about the three themes guiding the magazine’s publishing activities for the remainder of 2021 here.