On January 17, 2019, the United States entered the fourth week of the longest government shutdown in its history. An estimated 800,000 federal workers had already missed two paychecks, and the mood in the nation’s capital was forlorn. As an educator at a private Washington, D.C., university, I went back to work to begin the spring semester, while most of my colleagues in the city’s cultural community were forced to stay home. Many of them were angry, frustrated, and melancholy, worried about how they were going to make their rent payments in one of the most expensive cities in the nation and struggling to feed their families during a harsh winter. Metro stations usually bustling with bodies and energy were eerily empty, and despite groups of tourists walking the length of the National Mall, much of Capitol Hill and downtown felt like a ghost town. Restaurants and bars regularly flooded with employees exuded a shocking silence during lunchtime. During my morning commute, I saw civil servants standing in lines the length of city blocks for hours on end, waiting for a free meal.

Many of those employees hold positions at the invaluable network of art museums in Washington, D.C., namely, the federally funded Smithsonian Institutions, many of which were closed during the entire duration of the shutdown. While by mid-January federal employees had been guaranteed that they would receive back pay, the hundreds of independent contractors whose salaries come through funds that are not federally allocated were tense with the knowledge that their missing paychecks would never be reimbursed, or that they might not have jobs at all after the shutdown lifted. Many remember the powerful encounter between Tamela Worthen, a contracted security guard at the National Museum of African American History and Culture, and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, in which Worthen compelled McConnell to think about the human beings affected by the government’s decisions, expressing her own worries about losing her home and paying for her urgently needed diabetes medications. [1] Stresses such as these were amplified by knowledge of the shutdown’s disproportionate effect on Black workers and their families due to the high percentage of African Americans working in federal jobs and the disparity in wealth, financial networks, access to credit, and other resources that help people survive during difficult times. [2]

While there were many things on my mind during these dark weeks—including a serious acknowledgement of my own privilege and a desire to support my community of peers in any way that I could—the exhibition Between Worlds, a retrospective of the Alabama-born, African American artist Bill Traylor’s work at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, kept coming to the forefront of my thoughts. I had spent a few hours in the galleries with an artist friend prior to the shutdown and had wanted to return to see the exhibition again to take notes during the winter holiday, but the shutdown kept those plans at bay. Thwarted by the closure of an institution with the words “free and open to the public” stamped on its doors, my frustration only escalated when I realized that Traylor’s art (along with that of so many others) would not be available to the thousands of tourists and walk-in guests who meander around our nation’s capital every day eager to encounter the state of our nation’s cultural wealth. The objects and exhibitions that visitors have access to in federally funded museums during their trips to Washington constructs a narrative about what kinds of artists, ideas, and artwork our nation supports, what is significant to our understanding of our national history, and where our culture is artistically and politically situated at a particular moment in time. When these museums are closed, those opportunities to see and learn are lost. If we believe that art can give form to our most profound conditions as humans, what does it mean when our government excludes us from seeing it?

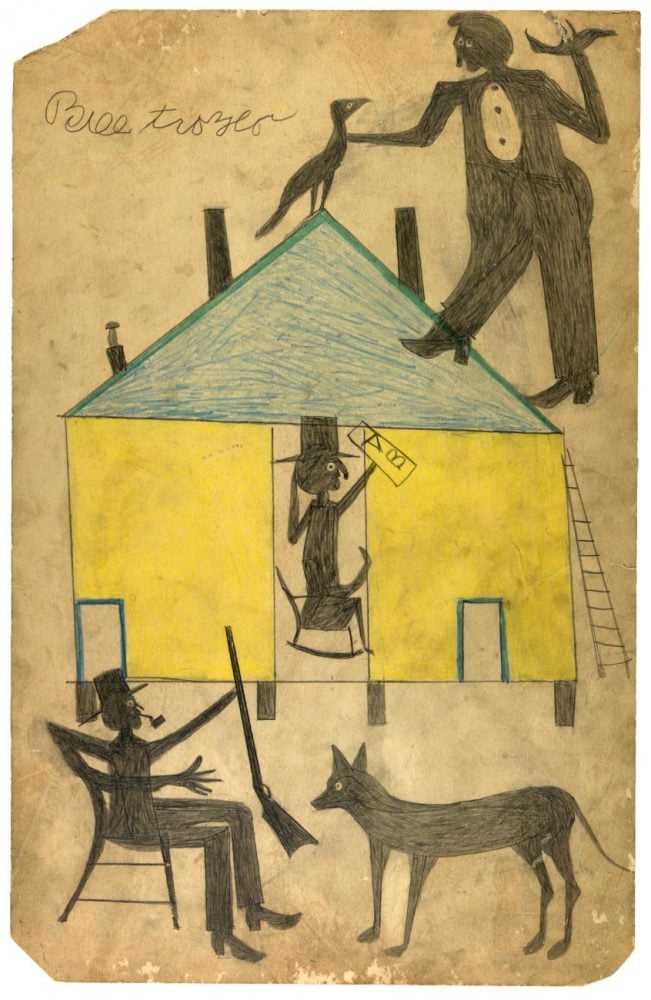

Exclusion is at the heart of Between Worlds at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, as Bill Traylor is an artist who has been, until recently, kept at the margins of our narratives of American modernism. Although he has been labeled an “outsider,” “naïve,” or, more disturbingly, a “visionary” or “primitive” artist in the past, this exhibition seeks to expand our understanding of Traylor’s life and art by selecting a strong constellation of images from the thousands in his oeuvre and presenting his works as central to the unfolding of American art in the twentieth century. It is important to state that Traylor is not a marginal artist but, due to the systemic, institutional racism and classism present in the art world, its institutions, and its historical caretakers, he and his works have been rendered marginal. Traylor’s exclusion from the narratives of American modernism would have us think that an ahistorical, detached, Greenbergian “push to flatness” is what modern art is about, not Black vernacular artists active at the height of the Jim Crow Era in rural Alabama. This is especially ironic considering that the history of modern art depends on the appropriation of the formal underpinnings of folk traditions and pre-modern, non-Western visual cultures that have been excluded from the institutional and mainstream cultural parameters of art, often by white, Western, privileged, and predominantly male artists.

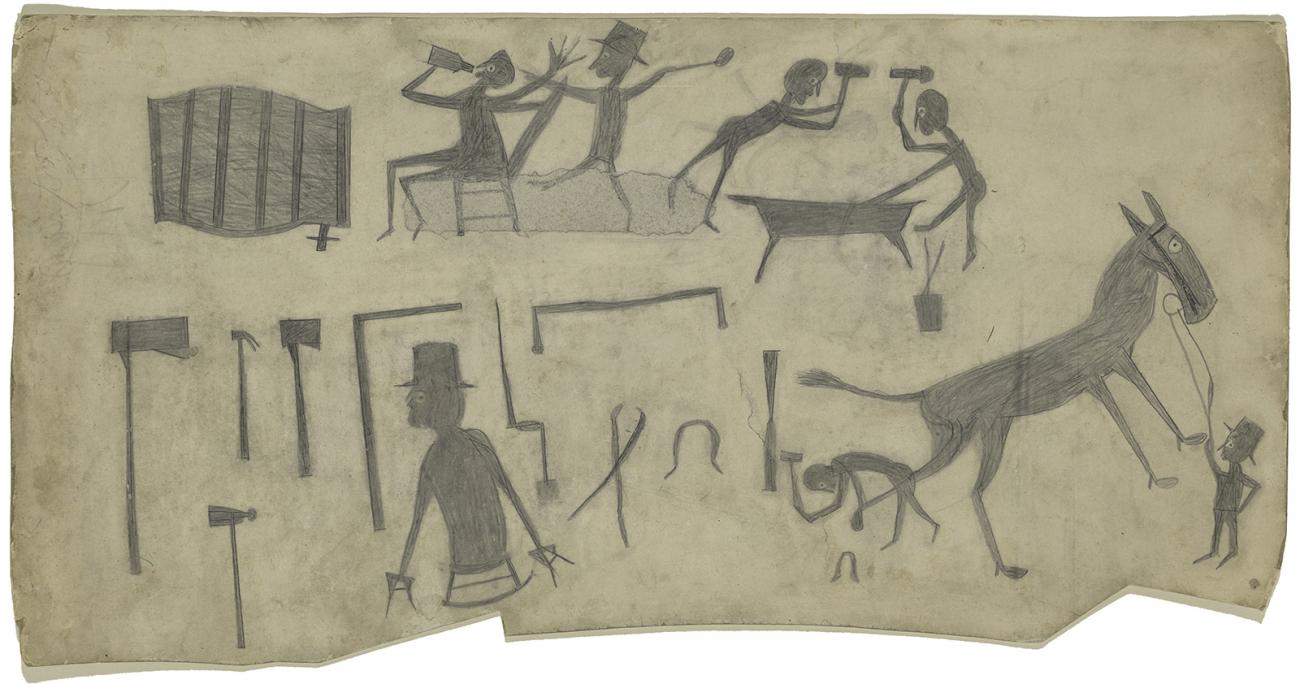

Born into slavery in Alabama in 1853, Traylor directly witnessed the Civil War, Emancipation, Reconstruction, and the Great Migration, and lived to see the foundations of Civil Rights discourse and action before he died in 1949. His first ventures into making visual art came in 1939 when he was in his eighties and living precariously in Montgomery. It is clear from the exhibition that Traylor’s acute attention to his art was not casual. The deep rigor of his encounter with the objects, spaces, and bodies that constructed his world and his creation of an elegant, direct style shaped over the course of ten years is palpable in this presentation. Using found materials such as cardboard, butcher paper, and wood, Traylor’s images are monuments to the ordinary. Unnamed men and women, dogs, and everyday objects such as baskets, vases, and bottles stand stark in a compositional field, charged by Traylor’s absorption of both the escalating language of popular advertisements in mass media and the dynamic social inequities and political conditions that framed his experiences in Alabama.

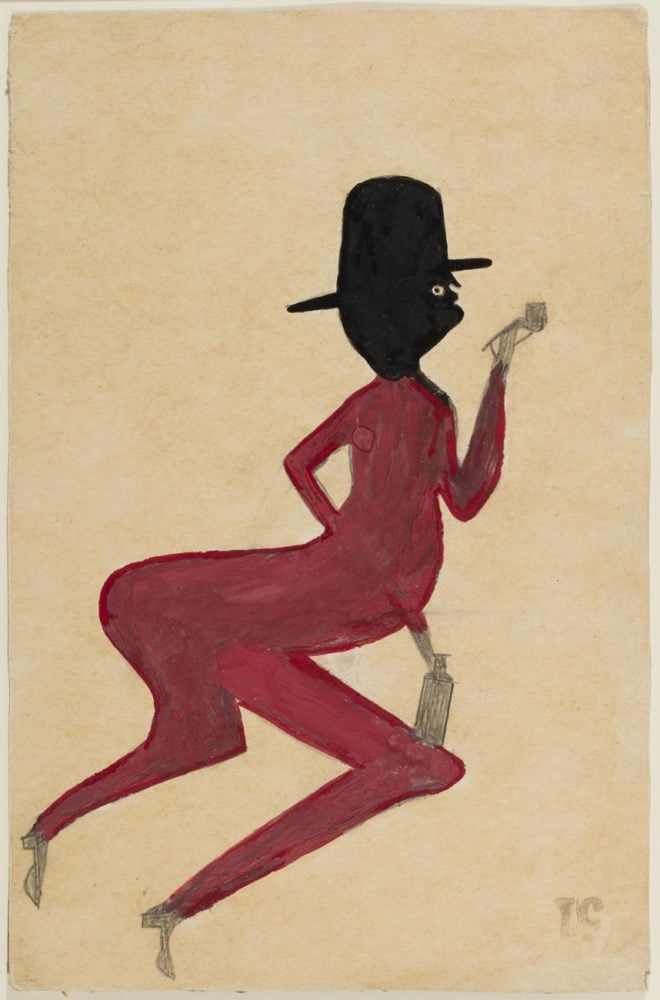

Two works stand out from the others in this exhibition: Black Jug (ca. 1939-1942) and Red Man (ca. 1939-1942), both rendered in pencil and poster paint on cardboard. If we consider the ways in which Grecian urns have stood as icons of Western civilization and culture across the ages, the legacy connecting Byron to Keats to Wallace Stevens’s “jar in Tennessee” is given a visual shape in Traylor’s noble jug. A vessel for water and wine, survival and decadence, Traylor’s perfectly centered black jug offers a counter to the Classical, symmetrical, measured (and presumed by many to be white) visual language of the supposedly “timeless” tradition of Western art and culture. The jug’s utility does not diminish its aesthetic quality, nor does the evidence of freehand drawing that contours the shape of this object; the clarity and precision of Traylor’s practice is impeccable, a détournement of the limits that Western art and its language of whiteness imposes on those bodies and artworks that threaten its supremacy. Liquor bottles, present in many of his works including Red Man, become long-standing icons of tension between freedom and oppression—a powerful symbol even when they don’t reach the lips of his figures. Bacchanalian pleasure finds form in these swirling bodies, dancing in the dynamic field of positive and negative space, as animated by the positive provisions of music and celebration as the more negative consequences of drinking. These are ultimately images of the Jim Crow South—a response to the unavoidable experiences of what it meant to be a Black man in a society working to legally terrorize and diminish the political influence, social mobility, and inclusion of people of color, and an intervention into the visual languages of Western culture that presumed Traylor to be an “other” and “outsider.” What nonsense Traylor and this exhibition make of his imposed externality.

The clarity and precision of Traylor’s practice is impeccable, a détournement of the limits that Western art and its language of whiteness imposes on those bodies and artworks that threaten its supremacy.

So what does this have to do with a government shutdown? As art institutions all over the world wrestle with their histories of gender exclusion, racism, colonialism, socioeconomic elitism, homophobia, corporatism, and slowness to create space and shift their policies to rectify these violent wrongs, we must, as visitor-citizens, ask ourselves what kind of artworks, artists, and ideas belong within the white walls of the federally funded gallery and what kinds of funding and funders do we want to support this institutional reckoning. These questions are urgent in the Trump era, a moment when a large sector of our government has been hijacked by a white supremacist working in large and small ways to diminish our progression towards a more equitable society, shrink our institutions and their capacities to serve a diverse population of citizens, and squash the faith of those communities and groups who recognize and are fighting against his insidious creed. Those with limited financial means and fewer socioeconomic privileges than others continue to feel the effects of Trump’s shutdown, and it remains impossible for me to not draw a line of connection between Trump and McConnell’s disdain for Black working-poor communities in the United States and the interruption of Traylor’s exhibition at SAAM this winter. Trump’s villainization of government employees and communities of color—along with collapsing financial and cultural support for public institutions and their services—are in alignment with this administration’s racist, classist, and sexist goals, and are made up of the same historical conditions of exclusion that allowed us to name artists such as Traylor “outsider,” “untrained,” “primitive,” and “other.” When opportunities to reimagine and restructure the narratives of (American) culture appear, as they have in this exhibition, and a government decides to shut (American) culture down, it is clear that, especially for those of us with power and privileges, there is more work to be done, and that the institutional responsibility to create new, more inclusive narratives is as urgent as ever.

Between Worlds: The Art of Bill Traylor remains on view at the Smithsonian American Art Museum through April 7.

[1] See Sen. Tina Smith (D-MN) and Rep. Ayanna Pressley’s (D-MA) opinion article “Federal Contractors aren’t getting back pay. Our bill could change that.” in The Washington Post, February 5, 2019.

[2] See Jamiles Lartey, “’Barely above water’: US shutdown hits black federal workers the hardest” in The Guardian, January 11, 2019.