courtesy the artist and the Birmingham Museum of Art

If the single criterion for a successful show were the quality of its images, Dawoud Bey’s The Birmingham Project would certainly fulfill that test. Bey, after numerous visits over the years to Birmingham with a desire to create a project there, worked through various community and religious organizations to arrange to photograph 32 sitters—boys and girls the ages of the six children who died in Birmingham on September 15, 1963, and adults who are the ages those children would have been today. He then combined the 32 images by association, referencing similarities between the adult and child subjects, to create 16 diptychs. The concept is straightforward in its simplicity but complex in its results.

Bey’s project is based both in history and historicity—it is framed as much by the actuality of its events as it is by Birmingham’s attempt, in 2013, to genuinely consider the implications, legacy, and momentum generated by the slogan (and the programming it labels) Fifty Years Forward. This overarching theme contextualizes the majority of cultural production, a great deal of which is by African American creators, that is being exhibited across Birmingham during 2013. The Birmingham Museum of Art situated the project within this framework, and to the extent that the works appear in a museum where, 50 years ago, African Americans were allowed to enter only one day per week, it is evident that at least the access, if not the equity, of the city has changed.

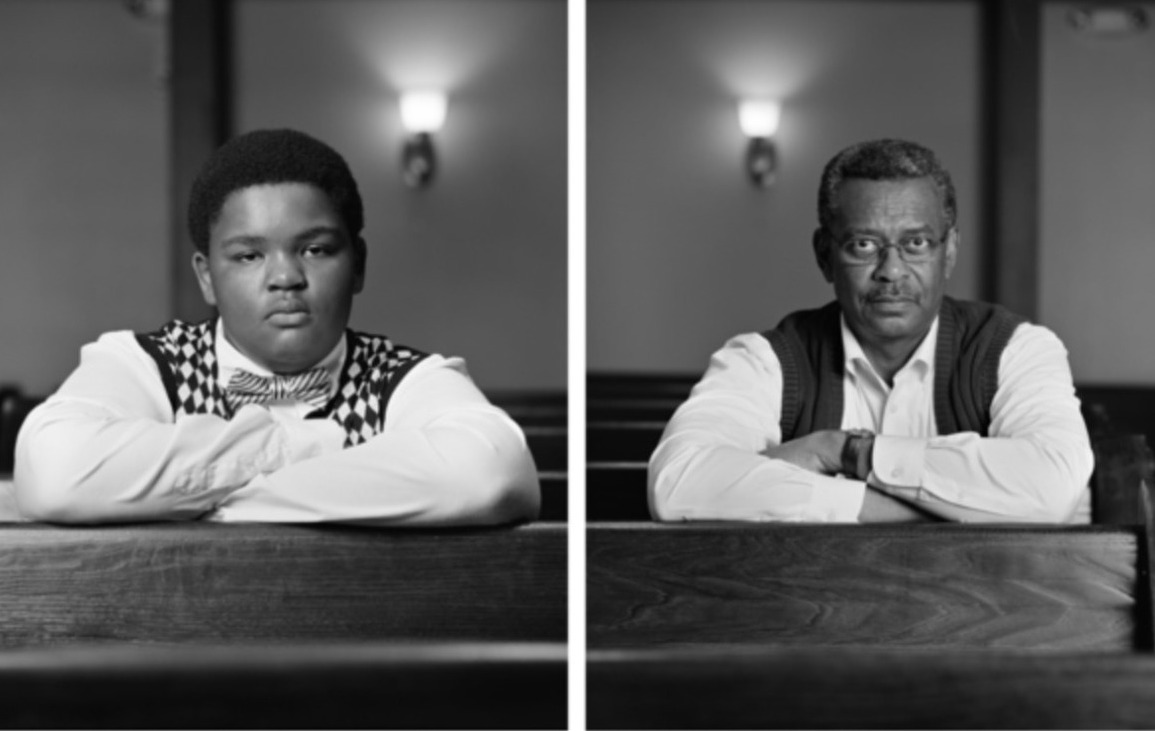

Of particular interest is the fact that the sitters were invited through the use of public outreach by venues that have traditionally served as community anchors within African American Birmingham. Bey, and curator Ron Platt, understood that the dialogues surrounding the subjects could not occur solely within the museum, just as the project itself could not occur without it. Bey chose two sites: the Bethel Baptist Church, in Collegeville, for its role in Birmingham’s resistance movement, and the Birmingham Museum of Art for its troubled history outlined above.

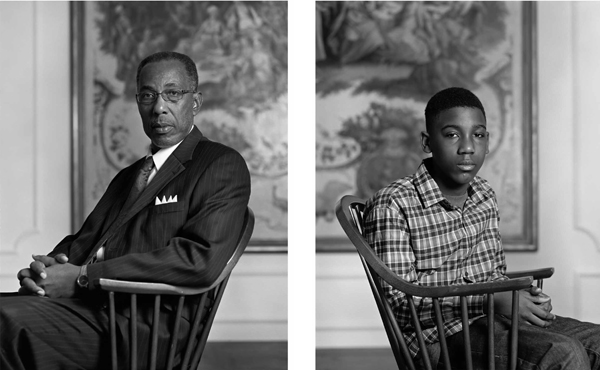

The halves of each diptych were conjoined after the fact, and although this approach may seem like a missed opportunity to create genuine engagement, instead it seems simply borne from necessity. The differences in age and generation would probably have meant that the younger sitters were on their best behavior with those they considered their elders. By photographing each sitter individually, Bey was able to create a sense of ease that allowed the sitters ultimately to relax into the chair, or rest their arms on the pew, or find a comfortable position that doesn’t seem posed. As Platt explains in his catalog essay, Bey has a subtle ability to “match people who shared physical features, manner, gesture or more intangible characteristics.” The relationships Bey creates are not happenstance. While they may or may not lack the tension that could have occurred if the subjects had been photographed together, the simple connections created by gestures like the mirroring postures seen in Janice Kemp and Triniti Williams, or Michael-Anthony Allen and George Washington highlight how each of Bey’s sitters is similar in his or her difference. Even more tension exists in the images where Bey moves away from mostly mirrored demeanor and instead places the sitters’ relationships elsewhere. Consider Mary Parker and Caela Cowan, in which Parker is seated in three-quarter view, whereas Cowan sits square to the camera. Here, both Ms. Parker and Ms. Cowan project a sense of gravitas, and each engages viewers through directness.

One should also consider Bey’s choice to print the works in black and white and, in Ron Platt’s words, to imbue the images with a “sense of the past.” Bey understands that for generations, and in many communities, the experience of portraiture itself was marked by mass-produced studio portraits. It is possible that for many of these sitters this project may have recalled that experience, which may have been their first formal portrait sitting. By displacing those predominantly color images, and by choosing black and white, Bey connects the contemporary images to the history of place and of personal experience. The entire framework of The Birmingham Project could be summed up by the dichotomy of black and white, so it seems even more appropriate. Sadly, viewers are left to wonder if the four-peaked pocket square in Don Sledge and Moses Austin is a crisp white or a beautiful pastel color. Either way, the images are respectful.

As Bey explains, part of the process in The Birmingham Project involved constructing the circumstances by and through which his sitters could reassert their rights to the gaze. Compositionally he has each subject look directly into the lens, creating an image in which each subject stares directly at the viewer. While Bey’s gaze is certainly active, his sitters’ position is not. His seated subjects reference both the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church and the nonviolent protest of the sit-in, but at the same time they also embody a sense of patience and of the willingness to engage with the camera, making the process truly participatory.

The video that accompanies the exhibition consists of a split-screen projection in which the camera appears to roll past a range of culturally significant spaces. Some, such as the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, are identifiable, whereas others remain mere markers. Platt observes that Bey has placed the viewer in the back seat of a car, where he or she becomes one of the little girls only moments from tragedy, the viewpoint set low beneath the car doorframe, looking up, the signifiers of home and community represented only by roofs and chimneys. Bey chose this more poetic, more evocative approach, leaving aside imagery that more directly reflects the contemporary issues of Birmingham. How could he have simply pictured its ongoing segregation, economic and social now rather than legal; its white flight from the municipality of Birmingham itself, making the city both more African-American and more impoverished; and its struggle with crime, particularly black on black crime?

What Bey’s 16 diptychs leave viewers with is the opportunity to contemplate hope at the same time that they remember, metaphorically, loss, tragedy, and the passage of time. Bey wishes to speak softly on the issues that resonated loudly, first physically and then culturally, on that tragic day in September 1963. One need only think here of the words of philosopher Walter Benjamin in his essay “The Image of Proust”: “One does not proclaim loudly the most important thing one has to say.”