Bees buzzing. Guttural hums. Rain falling in waves, and the sharp crack of thunder. The sounds of a Southern spring emanate from the first floor of the Hammonds House Museum, where Masud Olufani’s Translocation & Transfiguration is on view. Only it’s the middle of winter—the exhibition closes on March 22, a few days after the spring equinox.

The sounds are coming from two artworks in the second gallery: Inclement Weather and Hive: Elegy for the Fallen. But this simulated time travel feels fitting. Indeed, Olufani is concerned with the process of moving, changing, and transforming.

That’s clear in the title of the exhibition. But it’s also clear in Olufani’s work beyond his visual art: he’s an actor and a host of the show Retro Report on PBS, a program that claims to offer “viewers a fresh perspective on current headlines, revealing their unknown—and often surprising—connections to the past.” In the case of Translocation & Transfiguration, physical and chronological distance incite feelings of displacement, discomfort, contemplation, and transcendence.

Take Cane Fields Number 1, a work in four parts. There’s a graphite drawing of a Black person with sinewy skin that appears tough but well-worn. Below that drawing is a copy of Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations, burned so that the bottom of the book resembles a lopsided arch. Mounted in a separate box beneath that is a sugar cane machete, nestled in a cushion of white and red toile featuring a white woman in a pastoral setting. And on the floor in front of it all is an unmovable display of red clay and walking canes.

The presence of the charred The Wealth of Nations is matter-of-fact. The book—first published in 1776—is anti-slavery in the guise of economic viability. When paired with the portrait of a person whose name is unknown but face tells the story of a million lives, the book seems soulless. Perhaps in Olufani’s narrative, this copy of the book was thrown into one of the fires that blazed in the boiling houses where enslaved people were often burned as they processed sugar.

But there’s a subtler message in the interplay between the time-worn machete and the soft cradle of fabric that holds it. The idyllic field scenes printed on the plush toile fabric are nothing like the sugar cane plantations where enslaved people toiled. The machete, mounted as if it were a trophy, is sharp, cold, hard, and heavy. The people who would have used the machete to work the fields knew hardship well, while the people who owned the plantations lived cushy lives provided for by the enslaved people.

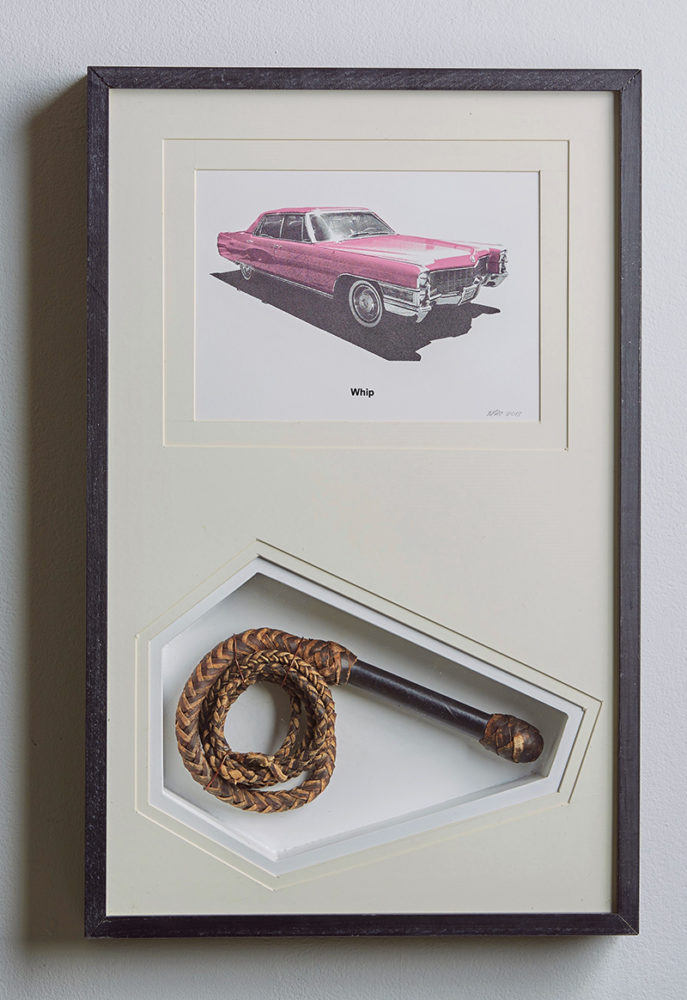

This kind of juxtaposition is an effect used throughout the show. Many of the works take no effort to conceal their meaning under layers of inferences. For instance, Bitch/Bitch? pairs an image of a dog labeled Bitch with a photo of a stately Harriet Tubman labeled Bitch? The commentary obviously addresses usage of the epithet and oppressors’ perceptions of Black women, specifically those who have no qualms about their power and humanity.

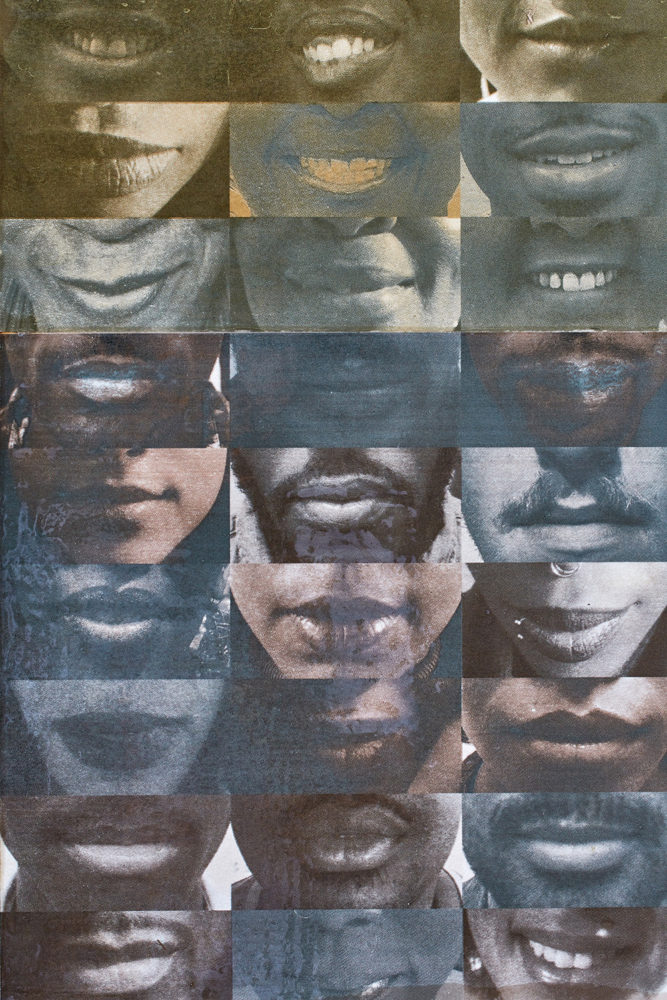

Soup Coolers, a title referencing the term used to describe the size of Black people’s lips, is pretty on the nose. The artwork is primarily composed of a serigraph featuring dozens of images of disembodied Black lips. But in the middle of the print, Olufani has placed a Campbell’s chicken noodle soup can next to a textbook-like explanation of the history, meaning, and usage of the pejorative soup coolers. The wall text for the artwork also provides context for the term. Again, Olufani bridges the gaps between time and perception while inviting the viewer to question those gaps. Black lips have been condemned; Black lips have been objectified; Black lips are now sought after. The serigraph and soup can, propped up in its wooden container, could have been suggestive enough on their own. But with both lengthy explanations, Soup Coolers feels more pedantic and less like an act of collaborative questioning.

The Ballot AND the Bullet, on the other hand, stirs in the viewer that visceral sense of incredulity, ambivalence, fear, and determination that Soup Coolers is missing. A blue ballot box sits on top of a white table. A black handgun attached by a steel arm to the ballot box points directly at the viewer who stands in front of the box. Even this trio of colors—black, white, and blue—reads as a poignant statement about violence, patriotism, identity, and courage in America. As you peer into the muzzle of the gun, you are torn between optimism and cynicism, concession and resistance, life and death. It stands to reason that the ballot box is empty.

Proximity is also used to great effect in the artworks Harvest and Freedom’s Price. In Harvest, the viewer peers through two rusty stereoscopes at the same scene of people in a cotton field—only one image is more faded than the other. In Freedom’s Price, viewers can stand between loaded slingshots and mugshots of dissidents, at once putting themselves in harm’s way and shielding the protesters from injury. In these artworks, the viewer is given the daunting task of being the link between what has happened and what will happen. At times, Translocation & Transfiguration recedes into simplicity and spoon-feeding, but elsewhere the exhibition rises to the challenge of combining candor with complexity. When it does the latter, it’s an entrancing call to action that urges us to learn from the past and have faith in the future.

Masud Olufani’s Translocation & Transfiguration is on view at Hammonds House Museum through March 22.