The Hunter Invitational was launched by The Hunter Museum of American Art in 2007 as a way of showcasing noteworthy contemporary artwork from the region surrounding its home, Chattanooga, TN. In the fourth iteration of the invitational, seven of the participating artists—Tara Hamilton, Andrew Scott Ross, John Douglas Powers, Vadis Turner, Amanda Brazier, Mindy Herrin, and Sisavanh Phouthavong—hail from Tennessee, with painter Charles Ladson as the one outlier based in Georgia. All works in the exhibition are characterized by an attention to strong technical resolution. Beyond that, the works are enormously disparate in terms of the artistic practices that produced them. In a text accompanying the exhibition, curator Nandini Makrandi carefully avoids the word “survey”: rather than selecting from existing bodies of work, she has asked the invited artists to create new work for the exhibition. The result is a visually varied group exhibition strengthened by its idiomatic diversity.

These artists may be considered in terms of both their position in relation to representation and their deployment of narrative. Tara Hamilton, Andrew Scott Ross, and Mindy Herrin each employ representational strategies to construct narratives through comics, installations, and ceramic sculptures, respectively. Painter Charles Ladson, sculptor John Douglas Powers, and painter Sisavanh Phouthavong use representation to examine phenomena of perception and illusion. Vadis Turner and Amanda Brazier eschew or suppress depiction to draw our attention to materiality and process, unmasking the story of how an object is made.

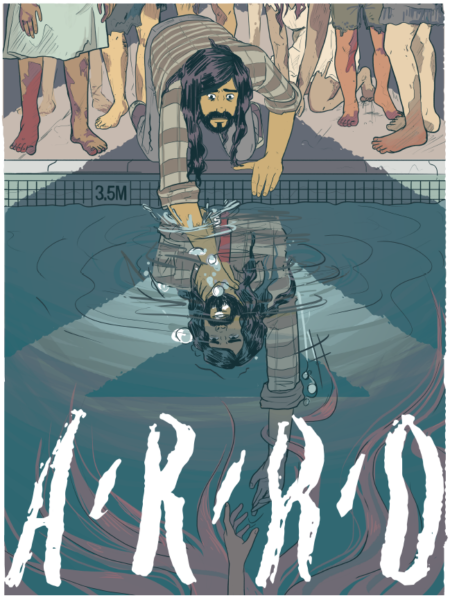

The well-staged arrangement of works by illustrator and artist Tara Hamilton came as surprise. Numerous digital prints, paper originals, and books are installed on the wall and in a glass-topped archival table. The centerpiece of Hamilton’s work is Arro, an ongoing graphic novel that she has illustrated in collaboration with author Alison Burke. Arro tells the story of a group of researchers moving across a near-future America that has been ravaged by an incurable water-borne disease. Hamilton has a sensitive, wandering line that encloses puddles of somber color to build figures and environments. Of all of the artists in the exhibition, Hamilton is the one who makes the most specific reference to the region. Her protagonists actually begin their journey in Chattanooga, though it is no longer the pleasant city we know today. The fictional figures in Arro have a faint relationship with Mindy Herrin’s exquisitely crafted ceramic figures. Amalgamated with natural objects and surface embellishments, the ceramic figures conjure quasi-mythical stories of hybridized and transforming bodies.

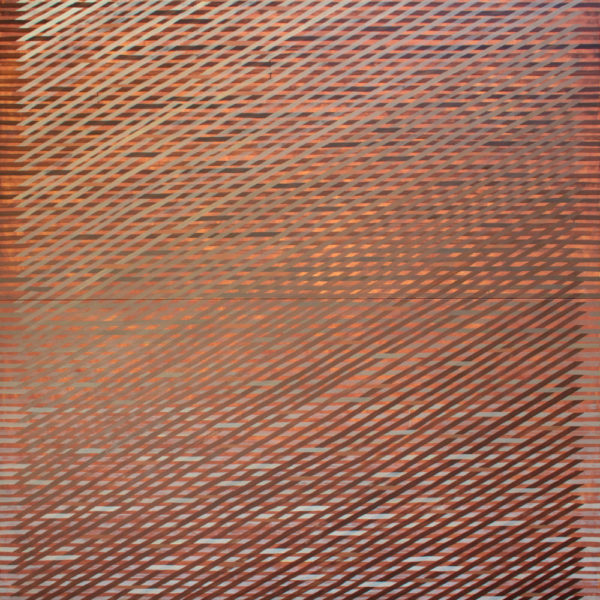

Amanda Brazier’s painting Exchange displays a pattern of overlapping horizontal and vertical lines, yielding a pattern of triangular peaks among other forms. Its woven lines allude to textiles, thatch, and other crafts based on intertwining. This work, along with Brazier’s other abstract paintings, is made from locally gathered earthen pigments. The handmade quality of her paint is discernible in the striations and runnels appearing in some of her lines, as well as the shifts in transparency. The works are surprisingly sensitive, sharing some resemblance with works created by artists such as Agnes Martin and Sean Scully. The end product, the painting itself, suggests a narrative of Brazier’s undertakings as she gathers and grinds the paint, then patiently and precisely applies lines to panels.

Charles Ladson’s paintings are more modest in scale and play deliberate games with how we perceive and read imagery. Ladson works with fairly quotidian objects in simple settings, such as the corner of a room, a tabletop, or the edge of a fence, for example. Objects are strangely truncated, or melded with human bodies that seem inert and statuesque. In Wheelie, an assortment of trash is gathered together beside a curb. On the left side of the painting, the lower portion of a trash can is visible. The shape of a human bust rises from behind an old carboy-style bottle, a black cloth tied around its head. Ladson builds the surfaces of paint in a very strange way: distressed, speckled, and strangely muted both in terms of color and texture. His grays, meticulously painted, resemble some kind of cement or putty. Closer inspection reveals methodical spattering and splashing with solvents and thinned paint.

The formal disparities between the artists are overcome by the fact that they each have ample space and very solid staging. The number of pieces included allows each individual to define her or his own oeuvre. The different works may or may not have a dialogue with each other, but they make the case that a region (as the entire American South is often described) doesn’t have to be defined by its quaintness or its colloquialisms.

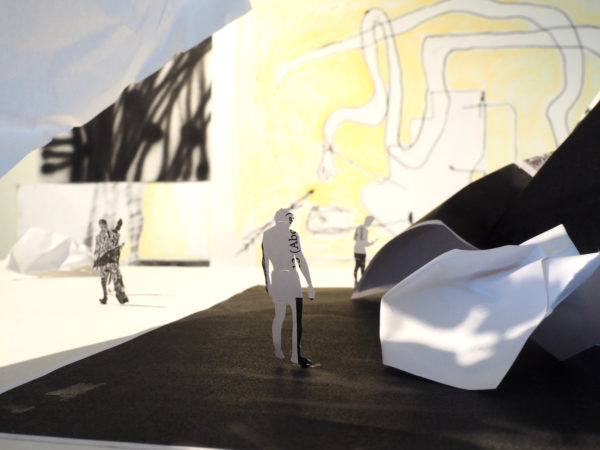

Slightly off to one side in the exhibition, hundreds of photocopies are stacked and strewn across a platform. Their black and white images depict Neolithic works from the Met’s collection and some of Gaugin’s Tahitian figures, as well as some classical works. Tiny figures rise out of them, carefully cut out and folded to populate this photocopied landscape. Some of the figures are human, some animal, a few of them are hunting and pursuing one another. This is Paper Caves, an installation by Johnson City-based artist Andrew Scott Ross, who also participated in the 2016 Atlanta Biennial at Atlanta Contemporary. In the visual narrative Ross presents, new cultures consume and exoticize the old, much like hunters destroying and then memorializing bison. There is, however, a more capricious interpretation that is equally available. Those tiny figures are a little bit like us, the art viewers, as we supplant, interpret, and ultimately consume works of art, making them over in our own image. The varied narratives in The Hunter Invitational IV give us each the opportunity to do just that.

The Hunter Invitational IV is on view at The Hunter Museum of American Art in Chattanooga, TN, through December 30.