Featuring fifty-five works by fifty-six artists, the 2020 Louisiana Contemporary Presented by the Helis Foundation exhibition at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art is considerably larger than its sister shows of years past. By design, the show features works drawn from across the state, though curators acknowledge an inevitable tilt towards New Orleans. Painting and photography remain prominent, but LAC 2020 also includes a solid number of works in video, animation, mixed media, found objects, assemblage, and porcelain.

Artists will always respond to context; of the topical issues addressed, unsurprisingly, the pandemic receives considerable attention. Clare Christine Sargenti’s Let Love Be Viral spray-paints her title over a stylized image of the virus; the multi-artist collaborative work indefinitely detained pairs a hand-stitched map of Louisiana––whose COVID outbreak sites overlay state detention centers––with powerful audio testimony from undocumented men and women who experienced those centers firsthand. Elsewhere, Ann Perich’s photograph determination or distrust depicts a Black man wearing a polka-dotted face mask against a stark black background. The tension here is generative, foregrounding the new normal in all its abnormality and alluding to the greater impacts that communities of color have suffered from the pandemic.

Numerous works in the exhibition celebrate the human face in ways that look beyond its detail and expressiveness, instead exploring its potential for beauty, dignity, and joy. Among them, Trenity Thomas’ photograph Teenage Summer shows a confident, even defiant young woman staring directly at the camera; blvxmth’s photograph Armstead shows an older Black man doing the same. Brendon Palmer-Angell’s quartet of drawings titled Irreplaceable; Taken by the Pandemic warmly commemorates four individuals who have lost their lives.

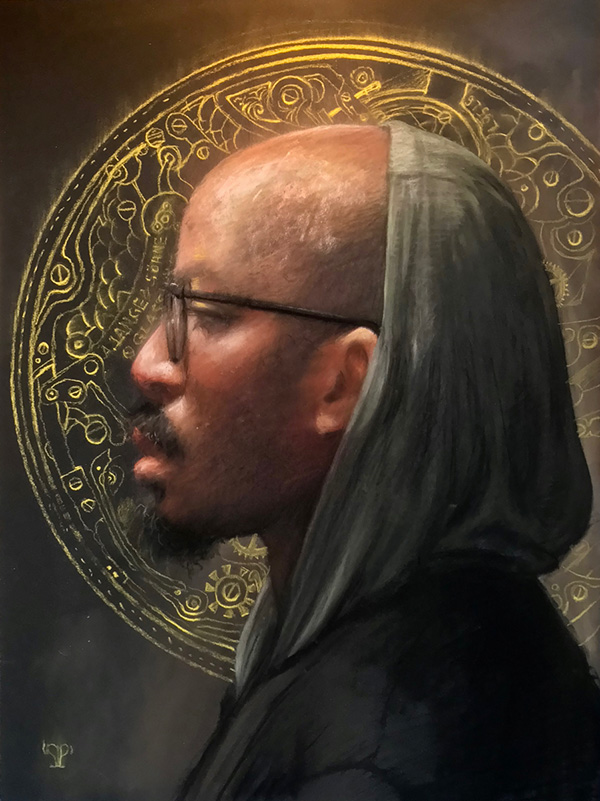

To see so many full, unmasked faces gathered together in the museum offers a combination of relief and hope: reclaiming what the last year has taken from us is one of the show’s greatest strengths. Numerous pieces address the sacred, whether through recasting traditional religious imagery or creating new mystical objects. Works by Rikailah Mathieu, Nicole Ockmond and Carol Peebles all depict Black people as saints, each bearing distinct halos recalling different art-historical styles. Peebles’ pastel of a young man in his prime renders soft head coverings and the subtle shades of a salt-and-pepper beard with exceptional skill. And in a year that saw continued violence against Black bodies, Mathieu’s portrait reminds us that the Virgin Mary of the Bible was a dark-skinned refugee girl, barely a teenager.

Other works address ongoing pre-pandemic issues: Matthew Phelan and Jacob Mitchell explore urban poverty and the legacies of the penitentiary system in Louisiana, and Abbey Kuhe’s Bycatch, in sgraffito-carved porcelain, depicts a shrimp trawler pulling up mermaids—celebrating the playful imaginaries of the state’s rich biodiversity even as it signals its fragility. Among the New Orleans-focused works, Noamy Sechooler’s painting Home is Sacred, Second Line for Reparations and Housing Rights /Solidarity highlights an issue afflicting many older culture-bearers in that city, who in recent years have been priced out of their homes. One of those culture-bearers, a Mardi Gras Indian, appears in a photograph entitled Culture by Rebecca McGirney but remains conspicuously unnamed contrary to best practice.[1] Given the sensitive history of photographers objectifying Indigenous people throughout the medium’s history, an explanatory text may have made this work’s inclusion feel more appropriate—especially given its placement just a few feet away from Nic Brierre Aziz’ prize-winning video Pimpin’ Ain’t Easy (White Barbies), which directly addresses the exploitation and looting of Black artifacts and creations through time.

Given how many issues continue to plague the state, it is perhaps unsurprising that landscape—typically a favorite subject of Louisiana artists—features less prominently in LAC 2020 than it has in previous years. Two exceptions stand out. Jordan Hess’ Souvenirs uses raw material from the landscape itself to create elegant, enigmatic keychains out of objects found along the banks of the Mississippi River. Andrew Lyman’s large oil painting, Darkened Meetings, uses swirls, drips, and splatters to muddy the scene, suggesting that little in this landscape is orderly or easily perceived: Only a few objects in the composition receive clean lines—a truck, a book, a collie dog’s upturned snout. With even the human faces a blur, the nature of the encounter is left to the unknown, given gladly to mystery.

Such mysteries are appropriate, given this last year of tension and uncertainty, in which we have suffered from so many crises with so few solutions. The gravity of the moment, along with the challenges that Louisiana has always faced, seem to drive each of the works in the exhibition—but none perhaps more than Greg Miles’ photograph Life, depicting an expectant Black mother in profile. Cradling both her breast and her swollen belly, she protects her own body and her unborn child. Her chin is set firm, and she gazes straight ahead past the edge of the frame—in a print whose deep negative space portends profound ambiguity, her eye is the primary source of light in the print.

Historically, Louisiana Contemporary has served as an annual record of the concerns that have animated artists throughout the state, and this year is no exception. Yet if this young mother—the embodiment of resilience, courage, and strength— is any indication, the abiding argument of the 2020 edition is that despite the trials, the costs, and the losses, there is still a great deal of hope to guide us through.

[1] Information on ethically photographing Mardi Gras Indians described here was sourced from the article “How We Do It: A Collaborative Interview and Photo Essay” appearing in African Arts: Volume 46. No. 2.

Louisiana Contemporary 2020 at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art in New Orleans, Louisiana is presented by The Helis Foundation and is on view through February 7, 2021.