When President Obama started singing “Amazing Grace” in the middle of his eulogy for the nine victims of the Emanuel AME Church massacre in Charleston, South Carolina, I remember most the expression on Bishop Julius H. McAllister’s face. Sitting right behind Obama, he suddenly broke out into a deep grin, chuckled, and nodded his head in approval. He clapped his hands, stood up, and joined in, along with everyone else. Carrie Mae Weems’s first full-length performance, Grace Notes: Reflections for Now, is named for that moment. Weems offers “notes” about the concept of grace in a multimedia event utilizing dance, video and still projection, spoken word by poets Aja Monet and Carl Hancock Rux, music composed by James Newton and Craig Harris, and a gorgeous performance of “Amazing Grace” by Alicia Hall Moran.

Coming a mere few weeks before the one-year anniversary of the Emanuel AME massacre, the Spoleto Festival in Charleston was poised to comment on that earth-shattering event. Though Grace Notes was billed as a piece about the Emanuel AME shootings, Weems rejected that view, wanting instead to take a macro level view of the history of violence against black bodies.[1] Weems is interested in patterns, in how the roles stay the same and only the names change. Weems tells the audience that her subject is a “history of violence,” as well as ideas of “constructing history,” a phrase that she used to title her 2008 video artwork Constructing History: A Requiem to Mark the Moment (see here for images and here for video).

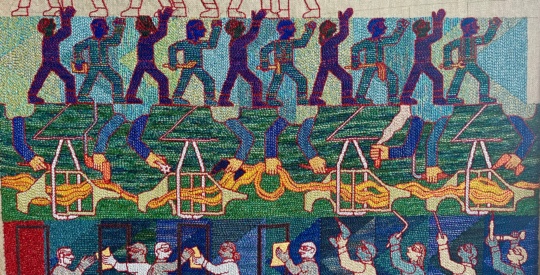

Weems showed the audience projected images of Constructing History, as if giving an artist talk, and explained that the piece involved collaborating with students (at the Savannah College of Art and Design) to restage famous photographs of pivotal moments in history, such as the assassinations of John F. Kennedy, Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King Jr, the capture of Angela Davis, the shootings at Kent State, and the victims of Hiroshima. Weems’s description of the assassinated then flipped into an accounting of assassins, listing Lee Harvey Oswald alongside George Zimmerman (who shot Trayvon Martin in 2012), Darren Wilson (the cop who killed Michael Brown in Ferguson), Peter Liang (the cop who shot an unarmed man in a Brooklyn housing project), Alicia White and William Porter (charged in the death of Freddie Gray in Baltimore), and now Dylann Roof, responsible for the deaths of nine people at the Emanuel AME Church on June 17, 2015.

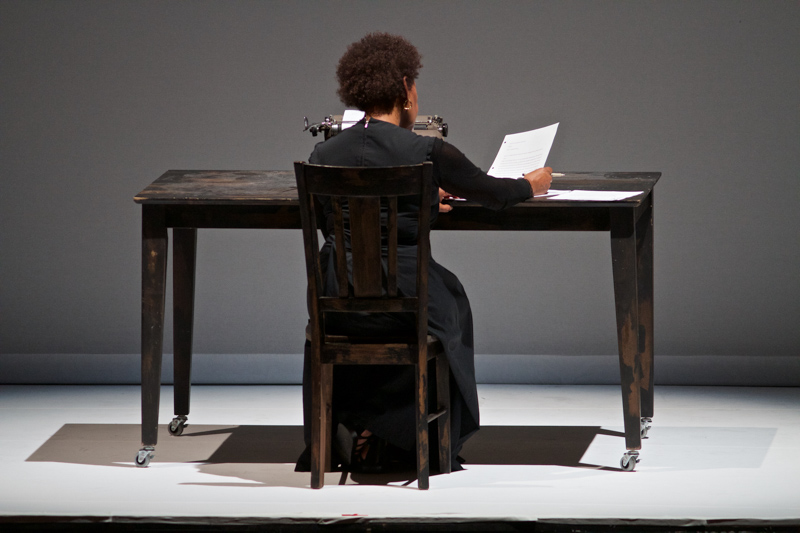

Grace Notes begins with Weems in a long, black dress, seated at a simple table before a typewriter. The typewriter implies the writing of history and history as a form of representation, bringing up the question of how history is often written by the victors at the expense of the victimized. We see from the back, just as we do in several of her photographic series (Dreaming in Cuba, 2002; The Louisiana Project, 2003; Beacon, 2005; Roaming, 2006; Museums, 2006). In these projects, Weems used her own body as a witness to history, occluding her face so that the viewer could identify with this anonymous figure as she inhabited different landscapes of memory.

Weems showed the audience projected images of Constructing History, as if giving an artist talk, and explained that the piece involved collaborating with students (at the Savannah College of Art and Design) to restage famous photographs of pivotal moments in history, such as the assassinations of John F. Kennedy, Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King Jr, the capture of Angela Davis, the shootings at Kent State, and the victims of Hiroshima. Weems’s description of the assassinated then flipped into an accounting of assassins, listing Lee Harvey Oswald alongside George Zimmerman (who shot Trayvon Martin in 2012), Darren Wilson (the cop who killed Michael Brown in Ferguson), Peter Liang (the cop who shot an unarmed man in a Brooklyn housing project), Alicia White and William Porter (charged in the death of Freddie Gray in Baltimore), and now Dylann Roof, responsible for the deaths of nine people at the Emanuel AME Church on June 17, 2015.

Grace Notes begins with Weems in a long, black dress, seated at a simple table before a typewriter. The typewriter implies the writing of history and history as a form of representation, bringing up the question of how history is often written by the victors at the expense of the victimized. We see from the back, just as we do in several of her photographic series (Dreaming in Cuba, 2002; The Louisiana Project, 2003; Beacon, 2005; Roaming, 2006; Museums, 2006). In these projects, Weems used her own body as a witness to history, occluding her face so that the viewer could identify with this anonymous figure as she inhabited different landscapes of memory.

The set of Grace Notes closely resembles one of the images from Constructing History, with two cutouts on either side of a wall suggesting windows, a clock stuck at three o’clock (a time she chose for the symbolism of the number three), a dead tree to the left of center suggesting a winter setting, and even bits of snow (a subplot implies a seasonal rebirth from the dead of winter to the growth of spring). A narrator tells the audience that we will be participating in the construction of history, and that the history will be embodied by the performers on the stage (such as dancer Francesco Harper) and that a woman (our muse) will guide us through this history. Eisa Davis, Alicia Hall Moran, and Imani Uzuri play the Three Graces, embodiments of the ancient Greek goddesses associated with beauty, grace, dance, singing, and joy. The history, though, is not specific. We are not given images of slavery or segregation or civil rights protests, for instance. Instead, it is a series of allegorical tableaux, many of which are drawn from Weems’s previous work.

In one tableau, a man is running on a treadmill. The speaker describes witnessing acts of police violence: “For reasons unknown. I saw him running, I saw him shot …” It is hard not to think of the North Charleston case of Walter Scott, shot in the back by a policeman, and the witness with a camera phone who recorded it. Throughout the performance, speakers stand at the sides of the set, holding scripts in black folders in their hands. They are the Greek chorus, bearing witness and offering commentary: “Your appearance changed, but you were always stopped, you were always charged, you were always convicted.” In another, we hear a snippet from Dale Carnegie’s self-help classic How To Win Friends and Influence People as we watch a black man struggle to carry a suitcase. We laugh at suggestions like “always be smiling” or “let the other person feel that your idea is his.” The laughter is grating though, hitting too close to home. My own experience of sexist power structures resonates with the text, which could refer to any situation of power imbalance.

Weems has used humor in the past to slyly get at the difference in how white and black lives are valued. In her series Ain’t Jokin’ (1987-88), racist jokes were printed at the bottom of photographs that illustrate and contradict them. In one of the best-known images from Ain’t Jokin’, Weems riffs on the Snow White fairy tale by presenting a black woman peering into a mirror at its white reflection, which tells the woman that without the white part of ‘Snow White,’ she can never be “the finest of them all” (see here). Weems had these jokes read out loud in Grace Notes, and paired them with her video Coming up for Air (2003-04), which shows two silhouettes — paper dolls in plantation hoop skirts — rocking back and forth as if pealing with laughter in slow motion. The audience broke out into guffaws at the next example: “What’s the difference between a white fairy tale and a black one? A white fairy tale begins with ‘once upon a time.’ A black fairy tale begins with ‘you motherfuckers ain’t gonna believe this shit.’” But when the next joke’s punch line included the N-word, the audience gasped, suggesting that maybe she had gone too far.

These humorous moments offered rare respite from the otherwise somber quality of Grace Notes. I found some of the spoken word too philosophical; the words washed over me rather than feeling like something I could follow and intellectually digest. But in other moments, Weems was simply a storyteller, and her first-person perspective successfully connected with the audience. Instead of offering us a rigid definition of grace, she described her process of trying to define it, calling her mother, her pastor, and her friends to ask what they thought grace was. She concluded that grace is maintaining dignity and humanity, the “core of one’s self,” throughout difficult times of struggle. Her subject is not, after all, the violence itself; it is the grace that lifts us out of violence, that allows us to carry on, to try to found a world without violence.

“What about the idea of grace in the service of democracy?” Weems asked the following day at an interview session with CBS correspondent Martha Teichner. That is where grace comes in: to be able to hold on to the promise of democracy even in the face of evidence that our current state is not fulfilling that promise. So Weems gives us a kind of homage to martyrs, climaxing with a procession of names on the screen. Read out loud, every line begins with “commemorating”: commemorating “all of the fallen and those who have endured”; commemorating Alicia Garza, Opal Tometi, and Patrisse Cullors, the women who started Black Lives Matter; commemorating “every black man who lives to see 21.” The list includes Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, Tanisha Anderson, Dontre Hamilton, Aiyana Jones, Darrius Stewart, and too many more. Among the startling litany of names, there were nine that rang loudly for anyone connected to Charleston. The speaker’s voice was shaking as she made her way through the names of each victim of the Emanuel AME church massacre.

The roll call leads to the inevitable question of what are we to do. “We could march. We could strike. We could say something.” Her interlocutor, Carl Hancock Rux, asks, “You’ve got to do something, right?” Weems responds with a simple no, surprising the audience. Grace is not a solution; it is the deus ex machina that abruptly resolves the plot. The point of Collier’s forgiveness is that Dylann Roof does not deserve it. He receives it even though he does not earn it. It is the strategy of rising above the fray, of not holding on to anger that could eat away at a person year after year after year.

The grace that Weems gives us is to bear witness by commemorating—to reflect and protest. Grace Notes featured step dancers from the Brothers of the Tau Eta chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha at the College of Charleston: a stomping chorus line that first comes out after the roll call of assassins, wearing Black Lives Matter t-shirts, and then reappears toward the end of the performance dressed for business in black pants, crisp white shirts, and striped ties. Their rousing performances were clearly savored by the audience and contributed a sense of dynamic hope for the future. Opportunities for reflection were offered by musical interludes that punctuated the tableaux, played against a dark stage, and the lullaby that Eisa Davis sang for Carl Hancock Rux, who was stuck in a big transparent plastic ball that he moved around the stage like a hamster ball. Once lulled into peace and calm, we were then confronted with video snippets of the beating of Rodney King, of Laquan McDonald being shot by a cop in Chicago, and Eric Garner being put in a chokehold by police on Staten Island. But these clips were intercut with footage of protest, reminding us that our job is to recognize what is happening. As the song tells us, “T’was blind but now I see.”

At times the performance was heartbreaking. At times it was beautiful and touching. At times it was funny, and at times it was confusing and disorienting. Some bits seemed too obvious, while others felt too obscure. In her interview the next day, Weems acknowledged that this was a work in progress, and that it would probably benefit from more shaping. It lacked the firepower of Lincoln, Lonnie, and Me (2012), which I saw at Prospect.3 in New Orleans and considered a tour de force. But it’s also a different kind of work, in which, Weems explained, she functioned more as a director than an author. It is inevitably flawed, but some of the best artworks are flawed. It reminds me of Katherine Hepburn in the 1940 movie The Philadelphia Story, shouting out, “My feet are made of clay, made of clay!” To be human is to be flawed. That is our grace.

[1] All interview quotes are from “Conversations With Martha Teichner,” 5 June 2016, Charleston Library Society.

“Grace Notes” was performed on June 4 and 5, 2016, in Charleston SC. The production might tour, but no firm plans have been announced. Weems is also in talks to publish the script.