For decades, New York City based artist Jordan Eagles has used blood — both human and animal — as a medium to push conversations about ethics and HIV stigma within American culture. More recently, Eagles has used blood donated from undetectable, HIV-positive gay men in his work — undetectable meaning a viral load so low it can no longer be detected by HIV tests — in addition to blood donated by men who have sex with men who are on the HIV-prevention drug PrEP. Full disclosure — I previously donated blood to Eagles’ Blood Mirror, an ongoing sculpture project at the time that visited Birmingham Civil Rights Institute in 2017.

Can You Save Superman II, Eagles’ latest exhibit to visit the South, is currently on display at the University of Alabama’s Abroms-Engel Institute for the Visual Arts through June 14, World Blood Donor Day. The viewable works accompany a virtual component that features an essay by Andy Warhol scholar Eric Shiner, who curated the exhibit.

Central to the many cycles of Eagles work since the 1990s is the different ways in which blood donation policies and cultural stigma in the United States have shaped the experiences of LGBTQ+ people and other marginalized groups. In America, blood donation is a regulatory mechanism within the lives of queer folks and the healthcare system; until 2015, men who have sex with men were outright banned from donating blood due to an archaic policy cemented during the AIDS crisis. Today, these queer folks are still banned from donation, unless they remain celibate for three months prior. People taking PrEP are not allowed to donate — period. Eagles, like many Americans, considers this blood donation policy discriminatory and rooted in HIV stigma. His focus on this issue feels particularly pressing as our world now battles a second pandemic in COVID-19, bringing with it, once again, a deep and crucial need for blood donation, and a disproportionate impact on communities of color.

collection tubes, residual blood, used medical gloves, paintbrush, digital print on acetate, preserved in plexiglass, UV resin; 15 x 12 x 3 inches. Image courtesy of AEIVA and Jordan Eagles Studio.

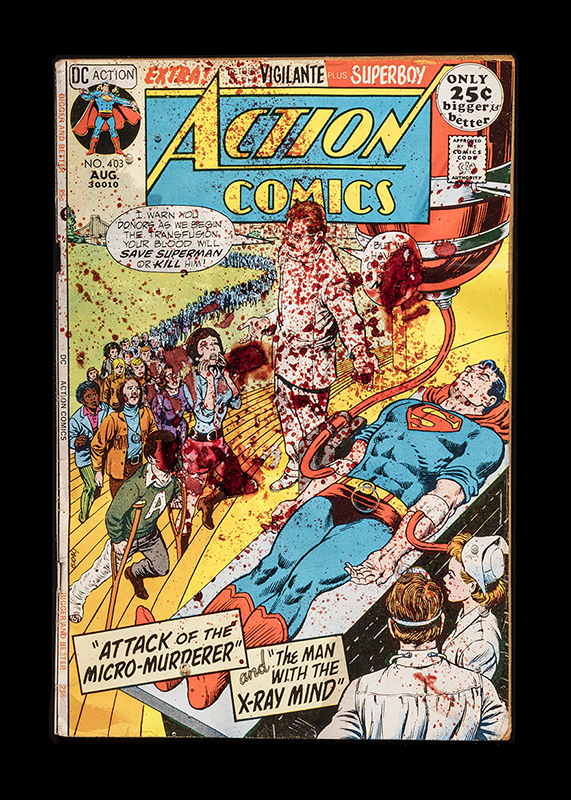

The central work within Can You Save Superman II repurposes a 1971 Action Comics entitled Attack of the Micro-Murderer, in which Superman is infected by a futuristic super-virus. Within the storyline, the citizens of Metropolis are called to donate their blood to Superman for a mass blood transfusion. In Attack of the Micro-Murderer, Eagles utilizes the blood of a gay man on PrEP to underscore a narrative about everyday citizens whose blood may or may not be deemed suitable to fight the virus in the first place. A sexually active gay man would’ve been able to donate blood in 1971, but could not take part in such an effort in 2021 — even with the COVID-19 pandemic continuing to ravage vulnerable communities.

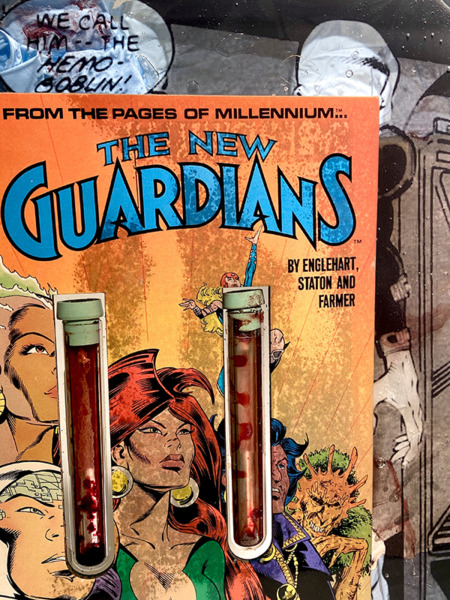

Other works on display in Can You Save Superman II include sculptures built around comic book storylines featuring The Hulk and a villain named Hemogoblin from The New Guardians comic book series. Both pieces are laser cut to hold medical tubes containing the blood of an HIV-positive, long-term survivor with an undetectable viral load, and an individual on PrEP.

Eagles is successful in positioning his continued exploration of the blood ban within the confines of our modern-day crisis. Can we save Superman? Not all of us — and not with the way this country is designed. But we can come together and try our best to engage in collective care when we need each other most — if those in power will let us.

Can You Save Superman? II is on view at Abroms-Engel Institute for the Visual Arts in Birmingham, through June 18.