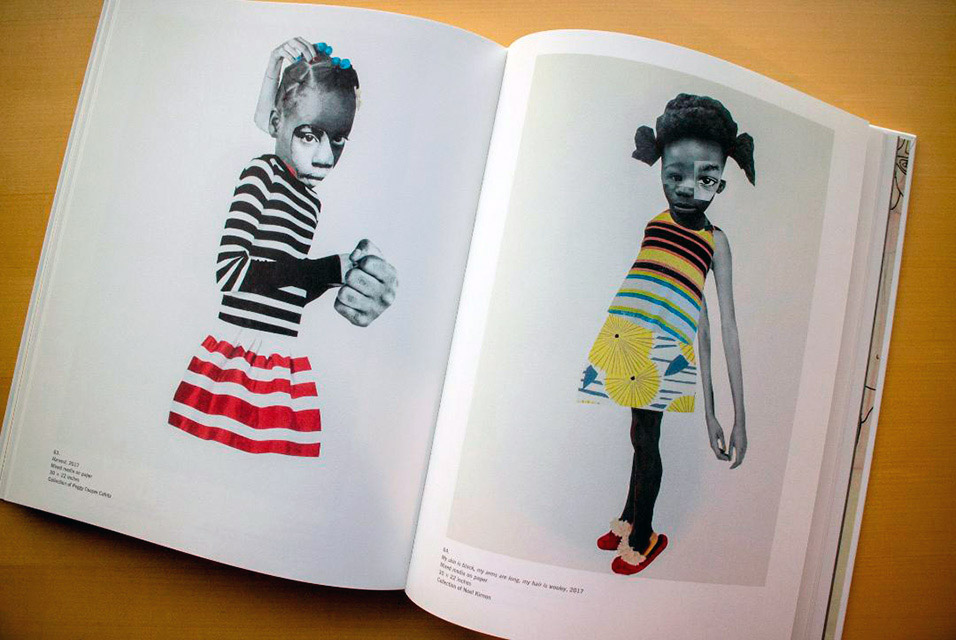

Once Deborah Roberts made the transition from figurative painting to her now widely-recognized collages, she lost some of her existing clientele. These collectors had grown accustomed to her romantic renderings of Black family life, work that garnered her attention as the “Black Norman Rockwell.” Her more recent work, primarily comprised of abstract collages of Black girlhood, did not resonate with them, or, as Roberts shared in an interview with The Village Voice, “They said I was doing work for white people now.” And while the larger white-dominated art world has swooped in on Roberts’s newer work (which resides in museum collections across the country including those of the Whitney Museum, the Block Museum, and LACMA), Roberts insists that she is still speaking to her previous audience and that she “shouldn’t have to simplify beauty.” She continues, “It can be complex, conceptual. We can meet that challenge.” In the 2018 exhibition The Evolution of Mimi and the recently published accompanying catalog, the Spelman Museum of Fine Arts has created a unique opportunity for critical engagement with and celebration of Roberts’s work.

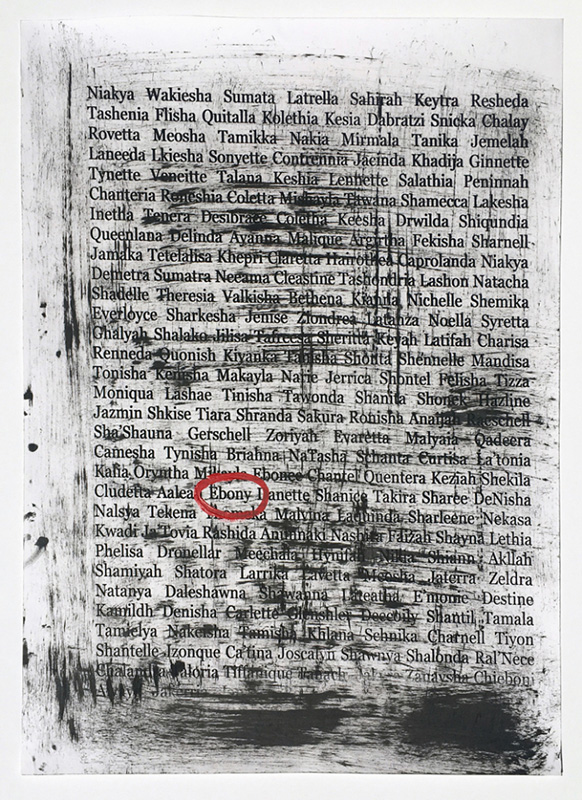

During the Spelman show, conversations bubbled around Sovereignty (2016) and the Pluralism series (2016). These works feature lists of Black American female names annotated with society’s insistence of their wrongness (some names feature the red underlining squiggle of a word processor, others are marked with anonymous comments “Why do Black people Name they kids this?”). As Andrea Barnwell Brownlee, Spelman Museum director and curator, recounts in her catalog essay, conversations about the serigraphs among visitors and staff sometimes became heated. You could imagine how these serigraphs—which narrow into Black female experience, on display at an institution which directly pursues the same goal—elicited contentions around social differences, with class perhaps being the most notable example in this context. The vulnerability Brownlee describes can, in part, be credited to her curatorial approach, which she outlines in the introduction of the catalog. There she sets out her aim for the 2018 show—to underscore the sociocultural and historical critiques which have informed Roberts’s work from the start of her career—while laying the ground for a multi-entry-point conversation led by curators, art historians, and writers.

Within the book, this conversation begins with Kirsten Pai Buick and Erin J. Gilbert, each responding to Roberts’s invitation to “look through double meanings and symbols” in her works. These readings examine Roberts’s work within the contexts of Black political and social life in the United States. These two essays are followed by two contributions that, in balance, privilege the conceptual artist’s voice. Through her conversation with curator Valerie Cassel Oliver, readers learn more about Roberts: her career path, inspirations, and intentions. In “Deborah Roberts: What’s in a Name?,” critic Antwaun Sargent maintains his generous style of art writing, pursuing the artist’s intention and responding in turn. With his focus largely on language as a theme of Roberts’s work, Sargent bridges the artist’s own ideas with the intellectual contributions of Roland Barthes and James Baldwin. Roberts’s assertion that naming your kids is a way of establishing history and gesture of imagining freedom and beauty meets Baldwin’s claim that people evolve language in part to control their circumstances, for instance. Sargent also places other aspects of Roberts’s work, such as her printing technique and her formal refusal of notions of a singular Black female experience (through techniques of fracturing and collaging) in conversation with two of her contemporaries, Glenn Ligon and Mickalene Thomas. With invocations of June Jordan and Warsan Shire, poets who have addressed the politics of naming in their work, Sargent hosts a constellated conversation about Roberts’s work.

Beverly Guy-Sheftall, a noted Black feminist scholar and Spelman faculty member, closes the catalog a brief history of the museum and her work within it as the founding director of Spelman’s Women’s Research and Resource Center. Along with the foreword from Spelman College president Mary Schmidt Campbell (herself an art historian and noted Romare Bearden scholar) and Brownlee’s anecdotes about visitor experiences during the show, this closing offers a reminder about the uniqueness of this institution: the only museum in the United States dedicated to the works of women from the African Diaspora. As Roberts recounted in an interview with Vice, “Going to Spelman for the opening of my show and being around those 18- and 19-year-old young Black women was eye opening for me. I got a lot of love and a lot of tears… You often don’t know what you are doing in the studio, and you hope that your message gets across, that people understand it, and I now know this is important work.”

The catalog Deborah Roberts: The Evolution of Mimi is available now from Spelman College Museum of Fine Art and the Georgia Museum of Art.