The tradition of a professional photographer—an outsider, often a Yankee!—coming down to document the deep, dark wilds of the South is well trodden. Perhaps it was the great Civil War photographer Mathew Brady who set this all in motion. There was also, of course, the acclaimed photographer Walker Evans, whose work defines our vision of the Great Depression. The currently working and exhibiting photographer Baldwin Lee, a professor at the University of Tennessee at Knoxville, may sound like a born-and-bred Southerner, but he’s actually a first-generation Chinese American raised in the Northeast who went to MIT and Yale. In 2014, the Savannah College of Art and Design commissioned Alec Soth from Midwestern Minneapolis to dive into rural Georgia kudzu to produce the work that would got into his exhibition “Georgia Dispatch.”

When we talk about influential photographers capturing the South, very often we are talking about outsiders looking in. In picturing the South, the distinction between native and visiting photographers often defines the work. While there are many celebrated Southern photographers, such as William Christenberry and William Eggleston, they are insiders with a particular perspective. It is the visiting photographers, often commissioned by major institutions, who tend to give the region the National Geographic treatment.

We can now add to this list Connecticut artist Andrew Moore, whose exhibition “Blue Alabama” is on view at Jackson Fine Art through July 7. Moore works like a photographic paratrooper, dropping in to places all over the world, from Cuba to Russia, adopting the visual language of documentary photography for a fine art context. Moore shoots with a large-format camera, perhaps one of the most tedious and persnickety processes available. Imagine having to spend an hour or more prepping for a single shot—and each time you click the shutter, you’re going to spend $50 on materials and processing. As a result of such an intensive, time-consuming process, the photographs can appear very manicured and staged, but the benefit of the large format is that tiny details render crystal clear.

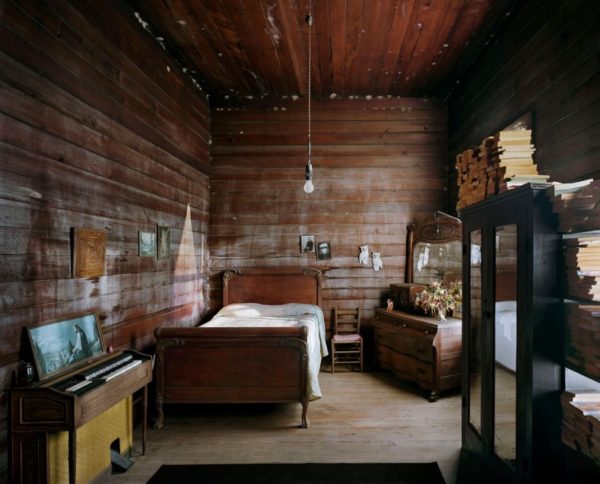

The way Moore crops, poses, and edits the scenes of his pictures reflects his interpretation of what the South is like. No distracting details detract from the semiotics of the picture; everything is framed so as to appear both old and new. Contemporary elements are usually cropped out, so that an image could seem to be from 50 or 100 years ago. For example, Library, Gaineswood, Demopolis, AL, 2017, features a grand room reminiscent of a plantation house, while Pearlie’s Black House, Wilcox County, AL, 2016, shows old furniture, a vintage electric organ, a faded picture of Jesus, and single lightbulb on a string. The only image with a clear reference to the modern day is On Time Fashions, Selma, AL, 2017, which has a few new-model cars in the background, and even then one car’s boxy front end evokes a vintage aesthetic. Like many other artists visiting the South, Moore’s interpretation reflects a pseudo-historical, “trapped in amber” quality. Do we really seem that old-fashioned in the South?

In technical and formal terms, Moore excels. In Black Door, The Temple Downtown, Mobile, AL, 2017, and Office on Walnut Avenue, Demopolis, AL, 2016, Moore plays with space and depth in striking ways, using the rule of thirds to compose the image. The intricacy of St. Andrews Detail, Gallion, AL, 2016, showcases Moore’s ability to capture infinitesimally fine-tuned details, like individual threads in a spider’s web. Large-format film lends itself to those details, but very few contemporary working photographers make use of its capability. Moore is one.

Even as a native Southerner, I too feel like an outsider to the South Moore depicts. I know nothing of the dusty, desolate trailer life pictured in Blue Sweep, Dallas County, AL, 2017. I haven’t encountered any hotels with piles of rotting vintage suitcases (surely accompanied by charming, deeply accented elderly owner) like the ones in his Demopolis Hotel, Demopolis, AL, 2016. Moore ventures into some of the depths of the South I’d rather not plumb. Some of the images feel like poverty porn, especially when you consider how much they cost to produce, and how much they sell for in one of Atlanta’s tonier galleries.

In that context, Moore’s references to the South’s racist past do feel a bit subversive. In Cotton Seed Barn, Marion, 2017, for example, a cotton bag hanging in the dramatically lit old barn evokes the shape of a Klansmen robe. Alongside a cache of cotton seeds, such associations are inevitable, if not intentional. Another image, Tremont School, Selma, AL, 2017, features a bird-shit-covered auditorium in a public school. It feels a bit like an indictment of the South and the ongoing effects of systemic racism. In these images, Moore’s documentary training comes forth—these aren’t just pretty pictures, they have a message.

One of the most enjoyable aspects of photography is viewing the world through another person’s eyes. But there is a difference between photographing wonders that are new and exotic to you (Moore, Soth, Lee) and appreciating the wonders that have always been a part of your life (Leigh, Chistenberry, Eggleston). Moore is a photographic explorer and intrepid outsider, documenting the South—for better or worse—as he sees it. While his perspective as a photojournalist lends the images a detached, anthropological curiosity, it also creates a depth and intention that makes them alluring.