On a clear day last summer, visitors to Long Island City’s Socrates Sculpture Park could see Manhattan’s imposing skyline peeking through Virginia Overton’s Untitled (Gem), a large, diamond-like sculpture constructed from recycled steel beams and trusses. That sculpture was one of the many focal points of Overton’s 2018 exhibition Built, notably the first solo exhibition by a woman at the famed site for public sculpture. Overton was born in Nashville, Tennessee, and now lives and works in Brooklyn. In interviews, she has recounted seeing her grandfather make small repairs to fences and machines while growing up, activities bridging the agrarian and industrial that are reflected in her own approach to sculpture. After studying art at the University of Memphis, she relocated to New York, beginning her studio practice in earnest in the early 2000s. Since then, she has created large-scale sculptural installations for New York institutions including The Kitchen and the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Overton told me in correspondence over email that her mode of installation art is “integrated into the space to a point that the space and the material meld.” She often uses industrial objects that resemble materials commonly discarded from construction sites as the basis for her sculptures, and the works’ materiality sometimes sets up a sharp contrast with their location. Arguably the best summation to date of Overton’s practice, Built had one foot in New York and another in the idylls of Tennessee: the striking landscape of the sculpture park was placed in conversation with more rural settings through Overton’s sourcing of materials and objects from her home state. Untitled (Late Bloomer), which features the bed of a pickup truck repurposed as a small pool dotted with lotus flowers, shows the multiplicity of meanings and contexts indicated by her practice. The sculpture points toward numerous, perhaps superficially contradictory references: the junkyard, working class machismo, and the fountain’s suggestion of regeneration.

Site-specificity was also an important consideration to the development of Overton’s exhibition at Socrates Sculpture Park. “When I was thinking about that show,” she said, “I spent a lot of time approaching the park from different places. I took the ferry, buses, walked—and I’d look across the river at it. I spent a great deal of time sitting in the park itself. One of the unique qualities that I was interested in highlighting was a focus on these various vantage points of the park and the city and their symbiosis.” The resulting sculptures both stood out in contrast to the park’s natural setting and reflected the broader constructed environment of New York City, becoming twisted reflections of all that towering steel and simmering industry.

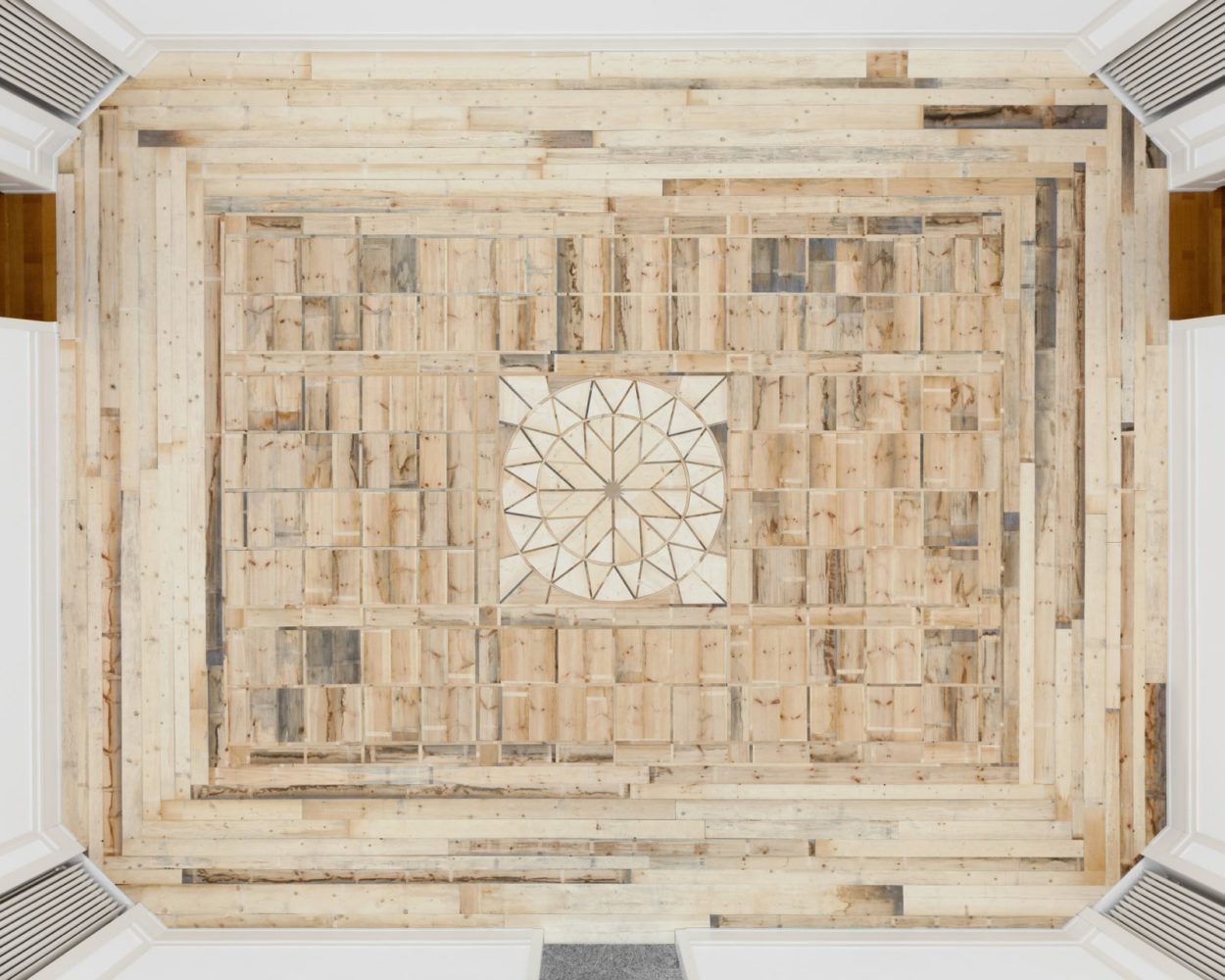

Overton also engages with the perceived gravitas and importance of the more conventional institutions where she exhibits by mining the history and design of these spaces for material and formal inspiration. In 2013, she created an installation at Switzerland’s Kunsthalle Bern that directly referenced the architecture of the storied museum. In the installation’s white, minimalist rooms, she used wood, mirrors, and other objects to create an uncanny reflection of the space. In an essay for the catalogue accompanying her exhibition, curator Howie Chen compared Overton’s practice to the Aristotelian theory of hylomorphism, the idea that being is a compound of matter and form. Chen asserts that Overton’s “recycling of everyday objects with clearly defined use outside of an artistic context allows her work to radically shift in different institutional and perceptive contexts” and “fluctuate between states of generation and deconstruction.”

Overton’s engagements with institutional history and compound contextual interpretations continued in 2016 at the Aldrich Museum of Contemporary Art with her sculpture Untitled (After Grosvenor), a fully functional weathervane based off on an image Overton saw during her research of minimalist sculptor Robert Grosvenor sitting on one of his works during the installation process. As a predecessor for the combined aesthetic appeal and functionality seen in Built’s sculptures, Overton said this installation “[delved] into this idea of sculpture being interactive not in the way that you could use it but that you could commune with the sculptures… I found this mode of intimacy interesting for large-scale public works.” To fully analyze an installation or sculpture by Overton, one must understand that interpretations of her work shift depending on the current home of the sculpture and the way the past lives and histories of the materials inform their presence in the space. The museums, galleries, and other settings that house Overton’s work directly contribute to the fluctuating meanings of the work. Because she does not fully disguise her materials through manipulation, Overton’s installations are never fully divorced from their materials’ original intended purpose.

Due to the admitted importance of site in her installations, it is tempting to impose meaning on Overton’s biography and understand her work as reflecting the places she has lived, including the rural South. Overton resisted this interpretation, saying, “I think that leaning on my background is too one-dimensional. Of course it is part of my understanding of the world, but that’s only one layer. I don’t focus on it singularly, rather I integrate it with all else that I’ve experienced and understood and continue to experience and understand.” While her materials might be routinely sourced from the South, their inclusion reflects Overton’s broader engagement with material culture in post-industrial America.

Overton describes her practice as “a refinement process wherein I add and deduct relentlessly until I have an exhibition that sits the way I want it to. That means there can be a particular tension in the installation. My definition of tension can mean a physical tension—like the way I’ve made some works similar to lean-to’s—or it can be a reinterpretation of the space by way of additive materials: changing the light, tone, and smell of a space.” More than a single meaning or facile read, what Overton’s installations provide is an experience of the tension between multiple possible interpretations, material associations, and perspectives—physical and otherwise.

Virginia Overton’s most recent solo exhibition was Água Viva at Bortolami in New York earlier this year.