The moment of Toussaint Louverture’s arrest has been depicted by many Haitian painters. Philomé Obin’s Arrestation de Toussaint Louverture (undated, but likely from the 1940s) and Jean Wilner’s Arrest of Toussaint Louverture, June 7, 1802 (1971) both portray Louverture confronted by eleven French officers wearing tricornes and bearing swords. Obin’s account shows a pink room, the Haitian revolutionary general in a slanted stance, hand on his sheathed sword, aghast at the intrusion. Wilner’s painting of the scene is similar, but the room is seafoam. The punctum is a vase of flowers knocked to the floor, strangely lying there unbroken.

Painting has accreted a political mythology around Louverture, an icon and national hero who has become a symbol of anti-colonialism and the abolition of slavery. Viktor El-Saieh’s rendition of the scene, Arestasyon Toussaint (2022), diverges from the realism of twentieth-century Haitian painters. El-Saieh’s Louverture is riding a rearing horse. Both man and steed are the same ethereal white, defiant, triumphant, even floating in a greenish void—but they are caught in a hyper-green net.

A modernist conceit that adds an air of science fiction, the painterly grid has them trapped. The painting, part of a recent solo exhibition called TIM-TIM at Central Fine in Miami Beach, is part of a new body of work by El-Saieh. The works are structured on tim-tims, a form of riddles in Haiti that resemble the American knock-knock joke format. Many of the paintings continue in the artist’s signature style—folkloric and historical characters doing their thing in lush, multi-level landscapes—but these paintings are different. “I’m [moving] from observing mythology and researching it, to dipping my toe in the production of mythology,” El-Saieh says.

Born in Port-au-Prince in 1988, El-Saieh was raised in Miami, Florida, but spent his summers in Haiti. His grandfather, Issa El-Saieh, born to Palestinian parents, has been called the man who brought jazz to Haiti. After his work as an innovative bandleader merging mambo, rara, and big band sounds, Viktor’s grandfather became an art dealer and ran a gallery in Port-au-Prince.

As a boy, Viktor fell in love with the work he saw. His own paintings are studies of Haitian history and legend, but also the art history of Haiti’s painters. They include political and military personages, and portray characters such as Fet Chaloska, the evil carnival figure with a giant mouth of terrible teeth. A student of international affairs, El-Saieh became engrossed in Haiti’s political history. Charles Oscar Etienne, the head of Haiti’s national police in the early twentieth century who is said to have murdered 150 political prisoners, inspired the Fet Chaloska mask that people wear in Jacmel, where the massacre occurred.

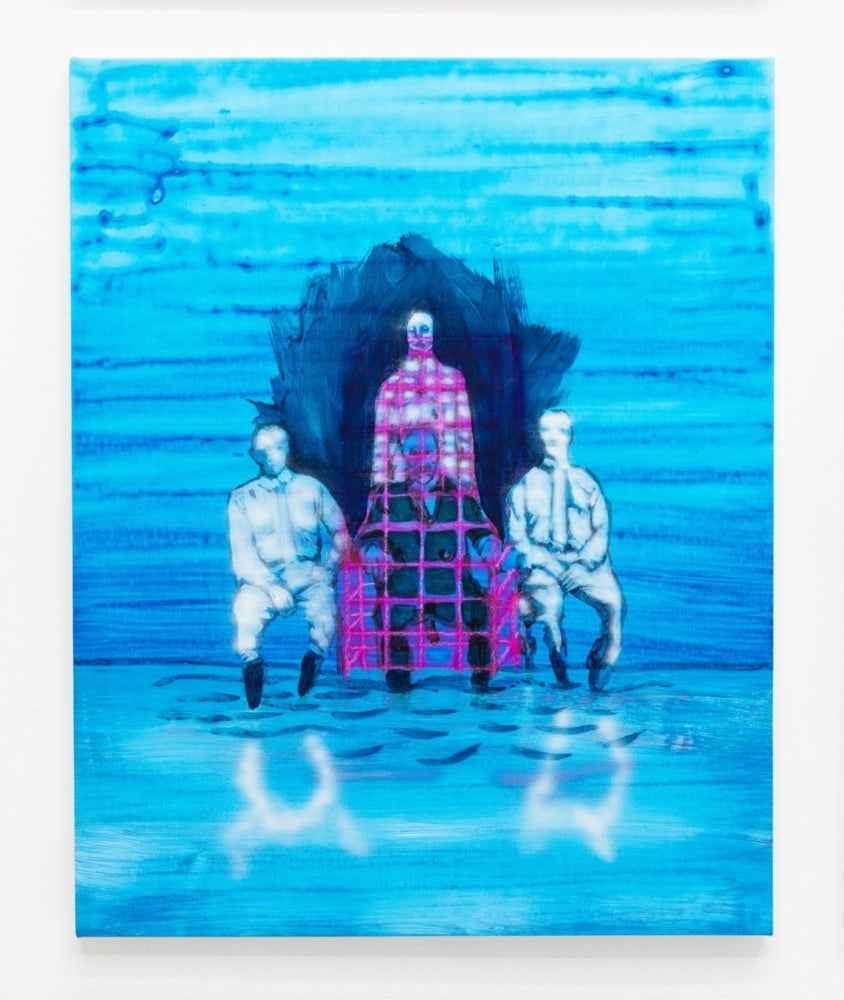

In this new body of work, El-Saieh deftly outlines the surreal links between politics and mythology. Instead of strict renderings of historical figures, he blends them with his own imaginations. In Tet chat (2022), a man in a suit is flanked by three men, one on each side and one standing behind him. They are in an icy blue chamber. Based on a photograph of Jean Vilbrun Guillaume Sam, president of Haiti during the U.S. occupation of the country, the men flanking the president in the photograph are American soldiers. In El-Saieh’s painting, a spirit-like figure hovers over the central figure, and both are covered in a red grid.

The use of glowing grids not only suggests entangling nets and jail cells—but also powerful cloaks and veils. In Eskalye (2022), a figure wearing a gown with a long train dances jubilantly at the bottom of a long, seaside staircase. The pink grid protects the figure, as a disembodied skeleton monster trails behind.

Also on the staircase is a cat, an animal that recurs often in El-Saieh’s work. “Ever since I was a kid I’ve been obsessed with cats,” El-Saieh says. “When I was a kid and I first realized what a cat was, I spent years just wanting to be a cat.” In the painting TIM-TIM (2022), a ferocious feline pounces on a group of fighting bandits. The cat is a merging of characters: the chat mawon, a wild feral cat that roams Haiti, and the lougarou, a werewolf-like cryptid that is similar to a chupacabra. El-Saieh sees the mythological figure representing the limits of vigilante justice. In trying to curtail the country’s banditry, the cat leaves its own trail of violence.

Besides numerous cats, the paintings contain other nonhuman, mythological figures. Dragons, with their dormant power, make a few appearances, and docile creatures appear in equal measure. In Manmbo (2022), someone rides a hummingbird, a mermaid breaches the water, and a trail of smoke from a fire ends in the grinning face of a mischievous, vaporous being.

The dichotomy of fire: a force for both life and death. As El-Saieh points out, the response to “Sak pase?”—the common Creole greeting meaning “What’s up?”—is “N’ap boule,” which means “we’re hanging out.” Translated literally, “N’ap boule” means “We’re burning.” We’re on fire, we’re alive.

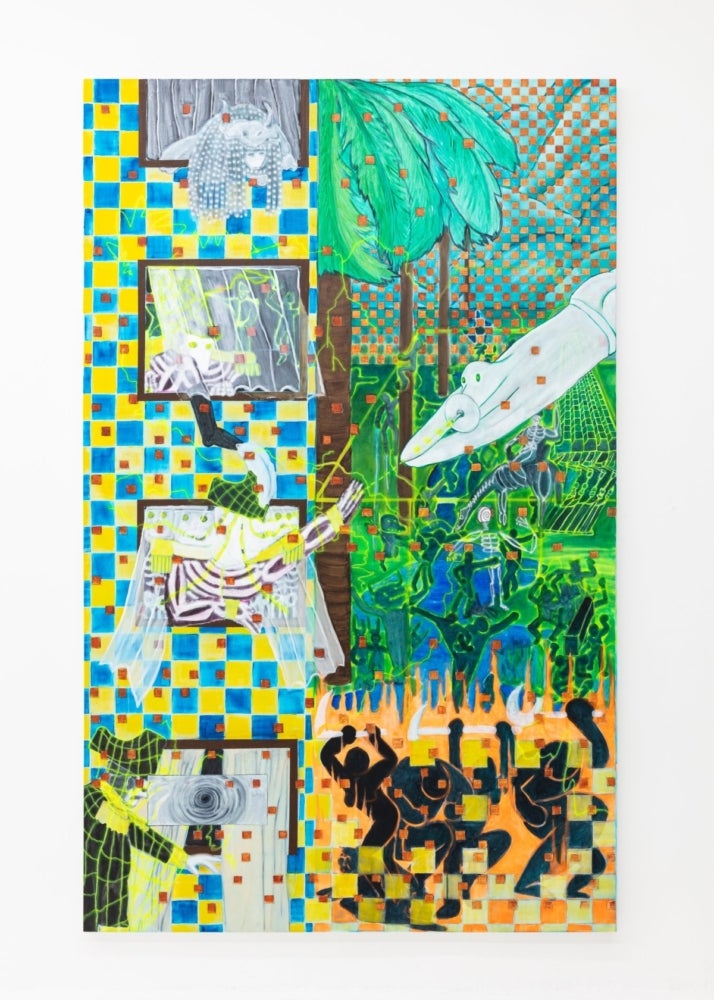

El-Saieh probes the ashes of foreign intervention in his country and finds the nuanced differences between nation and state. In a beautiful, disturbing painting titled Leta (2022), two skeleton figures in military garb stick out of windows. A masked flying figure swoops down, wearing a propeller on its nose, firing on the skeletons. The synchronization gear, which enabled automatic guns to be attached behind the propellers of aircraft, was tested in Haiti by the Americans during their occupation.

Leta is a masterful tableau, a commentary on the current state of Haiti which was rocked by the assassination of president Jovenel Moïse in 2021 and the flourishing of gangs, which some Haitians see as being more powerful than the government. A group of figures are consumed by fire in the foreground of Leta. In the middle ground, figures with glowing green outlines carry a coffin, while one climbs a palm tree. Simultaneous order and chaos is abstracted as a pattern of brown squares, exploding across the painting.

“This painting is about the current disintegration of the state, but also the role that foreign intervention has played in that,” El-Saieh says. “In the occupation in the early 1900s, the United States set up all these government institutions that are basically very similar to American government institutions. It’s this alien state that while possibly functional, is like a suit that doesn’t fit.”

Though the institutions of the state might be crumbling, the nation itself is less dissolvable. In Houngan (2022), a vodou priest shares plant medicine with the group surrounding him. A man holds a scroll, detailing, perhaps, the secret functions of the plants, traditions that date back to African spirituality—the cosmological lifeline to the time before enslavement. Again, a pink luminosity is present in the painting.

But instead of imprisoning the figures, it ripples through them, permeating the sea and the flora as well. “It seems like a lot of artists are trying to not be from the places they are from,” El-Saieh says of many contemporary artists who vie for a spot in the global, institutional art circuit.

“They’re rejecting this idea of a “Haitian artist,” or the “Cuban artist,” or whatever it is. Frankly I just kind of feel like, from the very beginning, I’ve been doing the exact opposite. To me, I’m basically continuing on with tradition at the end of the day,” El-Saieh says. “I can’t be anything other than what I am.”

This piece was published in partnership with Oolite Arts as part of a project to increase critical arts coverage in Miami-Dade County.