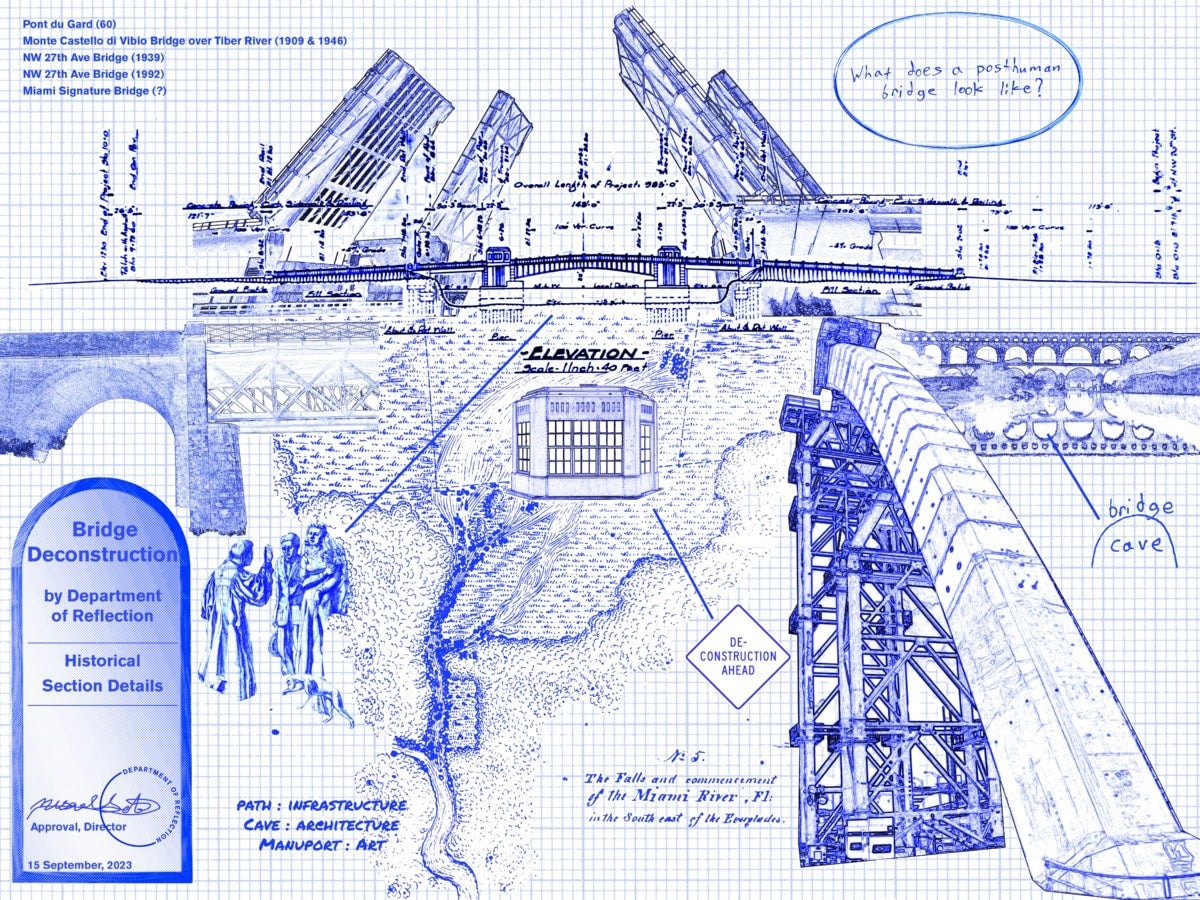

Miami Beach was founded with the building of a bridge. Though a visitor may see Lincoln Road and Wynwood Walls from the same bus tour, the place commonly thought of as Miami is actually composed of two cities with twin histories that continue to grow and warp together under the ceaseless sun and rising tides. Miami was founded twenty years before the first wooden slat was laid for Collins Bridge, but from the moment that construction began on the predecessor to the Venetian Causeway, the fates of the two cities were inextricably and often exploitatively linked. The Department of Reflection’s Bridge Deconstruction project has reconsidered this history because the looming cultural presence of the causeways continues to occupy the South Florida imagination today.

More than most places, Miami is always deconstructing and reconstructing itself, but even in a place with a short memory, every iteration holds on to scraps of what came before it, at least for the aesthetic appeal. The Bridge Tender House (Josephine Baker Pavilion) at the Wolfsonian-FIU is one of these scraps; for five decades, it stood above the Miami River at NW 27th Avenue before being saved from destruction and moved to South Beach to spend the last four decades as an art gallery.[1] The year-long Bridge Deconstruction began with a class at FIU and a call for artists and community members to reunite the Tender House with its lost bridge.

The Department of Reflection was founded in 2018 by artist misael soto in collaboration with the City of Miami Beach to hold up a mirror to the municipality and foster creative exchange between residents and the place where they reside. “Especially on the local government level, there is very little space for pause or reflection on what you’ve even done in the last week. It’s very reactive,” said misael, “Art really asks you to stop and reflect.” The Department’s work has included the construction of a gigantic board room in the Rotunda in Collins Park; a Special Commission on Roads; and trolley and boat tours focusing on local history. This past August, a bus tour offered by the Department took a group of curious Miamians to sites of banal bridge history across the county, including the resting place of the bridge Tender House’s twin in mainland Allapattah, which had not been as carefully preserved as its Wolfsonian counterpoint and lies covered in rust and graffiti. Misael wanted to bring it to the beach to contrast the two, but it was logistically impossible. “It’s kind of a great tale of two cities,” said misael.

More than most places, Miami is always deconstructing and reconstructing itself, but even in a place with a short memory, every iteration holds on to scraps of what came before it, at least for the aesthetic appeal.

Whereas the government can seem “bureaucratically designed to limit voices”, as soto describes, the Department’s Bridge Deconstruction partnered with project associates who ranged from historians to artists to engineers to tell the story of Miami, Miami Beach, and the bridges that unite and divide them. One of the most powerful activations was created by artist Loni Johnson, who led a large procession from the sea to an altar she constructed in the Wolfsonian on December 1 to honor the Black workers who built Miami Beach without being able to live on the island for decades.

“Sundown town” laws turned the bridges themselves into a site of nightly displacement, and Miami Beach still has a disproportionately small Black community and a reputation for police violence that has increased recently due to new laws criminalizing homelessness on the Beach. Johnson’s 5:31: Sundown Procession and altar honored the pain and division that these bridges represented as segregators between the white world of Miami Beach and the communities of color in Miami.

Framed by a wall of speakers recalling the legacy of block parties as sites of creative resistance[2], Johnson danced to the song “I’m So High” by Miami hip hop group Grind Mode. The performance honored a century of Black artistry and joy on the mainland as a “call-in and call-out” of the normally quiet lobby of the Wolfsonian, whose collection is sometimes reflective of Miami Beach’s oppressive history. Her altar included personal historical objects like her grandmothers’ jewelry box as well as references to a mural of 22-year-old Raymond Herisse, who was killed by Miami Beach police during Urban Beach Week in 2011. In 2020, the city removed the mural by local artists Jared McGriff, Octavia Yearwood, Rodney Jackson, and Naiomy Guerrero after its installation “at the request of Miami Beach police”, prompting a lawsuit from the ACLU.[3] “I do not often go to Miami Beach,” Johnson said. “I feel like that history, that narrative, is in the soil, on the sand, in the beach. That energy has not gone away. If you think about how Memorial Day Weekend is treated versus Ultra. How different bodies are treated in the space… A lot of the work is kind of rethinking how these institutions exist in our ecosystem, through work like [the Department of Reflection].”

Twenty years before Miami Beach was a twinkle in Carl Fisher’s eye, Miami was founded with a Black man listed as the first name on the charter.[4] Though much of the neighborhood that he lived in may have been lost to the bridges of expressways constructed in the 1960s, the cities of Miami and Miami Beach themselves stand as testaments to the hands that built them, and very few of those hands were white.

Part of the reason Miami and Miami Beach may have started to become so indistinguishable to a casual observer is because the bridges have once again become symbolic displacement. Whereas the Beach was once the center of art and wealth in the city, for the past two decades both have begun a steady march inland, perhaps acknowledging the inevitability of the King Tides that swallow the low-lying barrier island but leave most of the historically Black neighborhoods dry on the mainland. soto sees their project as a way to deconstruct the past while envisioning a more just future by challenging the complicity of bureaucratic structures. “I’m interested in how a complex reading of public space can lead to a form of abolition,” misael said. “And I do see the Department as kind of an abolitionist entity, through its alternative futures mentality. It’s almost like a kind of sci-fi, or just fiction, that leads us to future ways of working, living, existing in true community.”

Another response to soto’s prompt speaks to this mission. Miami’s first tourist attraction was a bridge—naturally constructed out of oolite through centuries of erosion at Arch Creek, and sacred to the Tequesta Native Americans who originally inhabited this land. In 1973, decades of automobile use and train damage took their toll, and it fell unceremoniously into the Creek in the middle of the night.[5] Using traditional Andean weaving techniques and contemporary practices, artists Sterling Rook and Agua Dulce constructed a new bridge made of fabric collected from the community, which was erected over the former juncture of the natural bridge on December 23 by a team of Miamians. In doing so, they honored Arch Creek as a place gathering. A bridge.

Few projects invoke the context of this place with as much ingenuity. Yet, the telling of Miami’s stories seems to always fall on its artists. “We are responding to this Miami that doesn’t want to see it, doesn’t know how to deal with certain things,” soto said. The Department of Reflection’s Bridge Deconstruction project will conclude on January 28, 2024, with a ribbon-cutting ceremony for the figurative bridge that has been constructed over the past year featuring local band Donzii, installations by artists Jessica Mueller and Chris Dougnac, and a second raising of Rook’s Miami Rope Bridge on Miami Beach.

[1] Miami Art Guide. (2012, November 23). The Wolfsonian–FIU presents untitled ([construction of good]): A site-specific installation by Bhakti Baxter. The Wolfsonian–FIU presents Untitled ([construction of good]): A site-specific installation by Bhakti Baxter. https://www.miamiartguide.com/the-wolfsonian%E2%80%93fiu-presents-untitled-construction-of-good-a-site-specific-installation-by-bhakti-baxter/

[2] Tompkins, D. (2019, September 23). An oral history of the Miami mobile DJ scene. Red Bull Music Academy Daily. https://daily.redbullmusicacademy.com/2019/09/miami-bass-mobile-djs-regulating-oral-history

[3] Pryor, R. (2023, November 1). Appeals Court backs Miami Beach decision to remove mural of police shooting victim. The Art Newspaper – International art news and events. https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2023/11/01/miami-beach-police-shooting-victim-mural-appeals-court-decision

[4] DeWitt, Grace. Black History: Miami’s Early Years, New Tropic, 22 June 2022, thenewtropic.com/black-history-early-miami/.

[5] “Arch Creek Historical Marker.” Historical Marker, 27 Oct. 2020, www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=77645.