During the 2017 BET Awards, the trio Migos won Best Rap Group while presenting their most iconic, and soon-to-be notorious, looks yet. Best known for the 2016 hit single “Bad and Boujee,” which maintained its place at the top of the Billboard Hot 100 charts into the following year, the rap group embodied newfound success and luxury. Their wealth was exhibited in floral-patterned button-up shirts, and tight leather pants, all selected by their stylist, Zoe Costello, paired with iced-out designer belts, and custom chains, rings, and watches created by their long-time jeweler, Elliot Eliante. Quavo, Offset, and the late Takeoff presented a dramatized and glamorized Black masculinity that leaned into both a traditionally femme and slightly androgynous style, despite their public persona that paradoxically hinged on the ultra-masculine, often including misogynistic and homophobic lyricism and speech.

Glamour, which comes from the Scottish word grammar, is historically and etymologically used to describe a form of illusion, charm, and mystery. As employed by pop artists and drag queens like RuPaul, Cher, and Madonna, glamour wields power in representation, allowing figures to project and perform their ideal, opulent persona. While these glamorized projections of self are often campy, dramatic, and inescapable from view, importantly, glamour is purposefully not true to life.[1] Black male public figures utilize glamour as a form of camouflage, or illusion with the intention of deceiving the consuming public.[2]

This ostentatious trend among Black male rappers allows them to tool or weaponize their dress, presenting a form of Black masculinity that becomes illusory. This implementation enables the performer to transgress class and gender lines.[3] The magical tool of glamour grants the individual the ability to pose as the unreal, subverting stereotypes, conventions, and expectations. Further, in the case of the Black male rapper, dress provides an act of resistance. To camouflage Black masculinity offers relief from the omnipresent and overbearing white gaze.

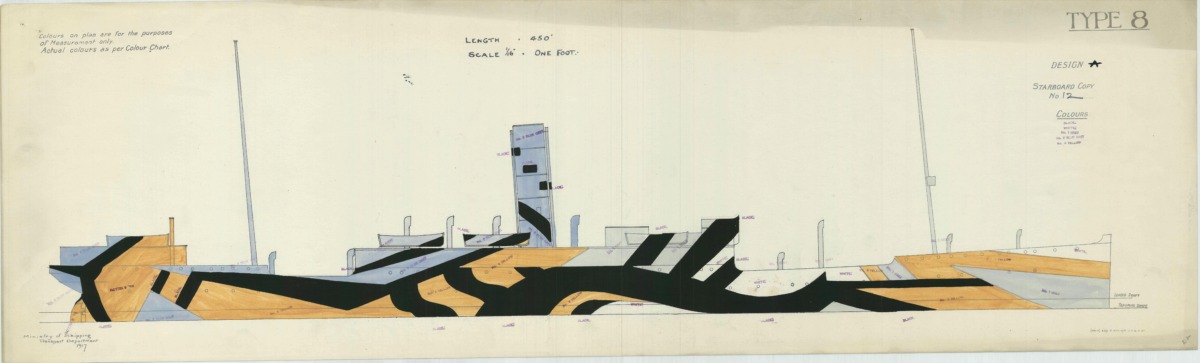

Camouflage is a tool of disguise and deceit, which allows one the capacity to mirror and/or match their surroundings. Yet, dazzle camouflage obscures. Created by painter Norman Wilkinson, dazzle camouflage was utilized in World War I on British and American warships.[4] The ships were painted in a black and white or red and white pattern to create an optical illusion to confuse or throw off their opposers. Rather than blend in, the intention was to make the ship difficult to target. “Razzle dazzle” weaponizes an intricate patterning to create deception, clouding judgment around the subject.

Taking into consideration the style and dress of Migos in relation to the tradition of dazzle camouflage, their luxurious presentation of self becomes a way to deceive. Taking inspiration from a long line of Black performers, the group implements a form of peacocking. Building on the mating practice of the tropical bird, peacocking is colloquially used to describe the phenomenon and practice of men using flashy clothing and accessories to attract a mate. At the 2018 Grammys, the group took inspiration from Black pop icon Michael Jackson. Each member wore a custom-made gold and black sequined jacket in the traditional military band style designed by Welsh fashion designer Julien Macdonald, echoing one of Jackson’s most well-known looks. Famously, the King of Pop also employed glamour and dazzle. The same year they attended the Met Gala, wearing pink, orange, red, and black sequined Versace suits also designed by Macdonald. This peacocking—the opulent and dazzling or “dripped out” choices in jewelry and clothing—made the rappers unmissable. Shrouded in luxury, though camouflaging themselves, their personas were on public view. Even the term “drip” is noteworthy. “Drip,” prominent throughout their song lyrics, originated from Atlanta trap music artists, describing the highly adorned, careful curation of an ensemble, referring directly to the over-saturation of the flashy, glittery, and expensive.

The intertwined relationship between self-fashioning and Blackness in the public eye—especially regarding Black musicians—has a history rooted in the unavoidable white gaze. As early as the 1970s, Black R&B, funk, and disco entertainers dressed in sequined, brightly colored, tightly fitting clothing. The early decades of hip-hop, however, took an alternative approach. Up until the late 1990s, sportswear and workwear were trending among rappers, with their display of luxury and wealth visible through custom-made jewelry and designer shoes.

Following sportswear and workwear trends, rappers found inspiration in the mafia lifestyle and aesthetic embodied through films like The Godfather (1972) and Scarface (1983). In the era of gangster and mafioso rap, the organized crime lifestyle was romanticized and glorified luxury achieved through monetary success. Artists like The Notorious B.I.G. embodied this trend with his infamous black suits designed by the New York–based clothing company 5001 Flavors complete with a hat and cane along with his own rap group Junior M.A.F.I.A. With gangster rap, self-fashioning took a turn, seen through artists like Snoop Dogg who upheld a pimp persona wearing bright suits with matching canes, hats, and furs, finished with a straightened, shoulder-length hairdo. His pimp fashion draws on the organized crime figurehead persona, placing value on a presentation of self that appears successful both in power and money, while also playing with gender. Recently, rapper Trinidad James continues the stylistic legacy of Snoop Dogg and Slick Rick, through his hair and nails, which he shares on social media.

When hip-hop music broke into broader (meaning white) popular culture in the 1990s, heightened popularity came with heightened surveillance. Black male rappers were demonized, and called dangerous by mainstream media outlets. In retaliation of these public perceptions, rappers began to use campy dress as a refusal of respectability. Black music is constantly faced with policing and surveillance, especially rap, and as a result, rappers turned toward a femme, glamorized style to visibly alter their perception. By playing with gender, rappers were able to set themselves apart from lyricism deemed violent and hypersexual.

To camouflage Black masculinity offers relief from the omnipresent and overbearing white gaze.

Today, Black masculinity continues to be demonized and criminalized in the public eye. Subsequently, Black male rappers express themselves through an alternative Black aesthetic that is deceptive and alluring, setting themselves apart from imposed violence, harm, and judgment. Instead, consumers become enamored with brightly colored, patterned dress and lavish adornment. While acknowledging though not denying a societally constructed Blackness, these performers’ public speech, persona, and lyricism are cloaked. Migos and other contemporary rappers continue to address the hustler and trapper lifestyle, glorify organized crime aesthetics, and depict a formidable character that is awarded high luxury. The same Black male rappers maintain their notoriety as problematic public figures, who are hypermasculine and employ misogynistic, homophobic rhetoric. Yet, they create a barrier separating and distorting their visual perception and character. Throughout rap history, stylized dress was informed by a desire to display success. Now, dress is a tool for subversion. Migos embodies this phenomenon, creating an intervention and fabrication of the Black male rapper through a performance of Blackness that is skillfully obscured by the luxurious, glamorous—dazzling.

[1] Terre Thaemlitz. “Viva McGlam?: Is Transgenderism a Critique of or Capitulation to Opulence-Driven Glamour Models?, ” Comatonse, 2008, http://www.comatonse.com/writings/vivamcglam.html.

[2] Here, I am choosing to refer to these two figures alongside Migos because of their public history with fashion. Lil Uzi Vert has always maintained an outspokenness when it comes to his styling, making note that he does not have a personal stylist. Gunna is best known for his courtside look wearing a Chanel overcoat.

[3] Thaemlitz. “Viva McGlam?”

[4] Patrick J. Kiger, “The WWI ‘Dazzle’ Camouflage Strategy Was So Ridiculous It Was Genius,” History.com, March 28, 2023, https://www.history.com/news/dazzle-camouflage-world-war-1.