In Benjy Russell’s photographs, “everybody gets the Hollywood starlet treatment.” According to the artist, “The sculptures do, the garden does, and I think everybody needs it,” he adds with a laugh.[1] Russell’s ethereal, dreamlike images often serve as documents of improvised monuments; his three-dimensional symbols and structures—referencing Russell’s Choctaw heritage, ’90s queer subculture, and other cryptic moments from his biography—are lit from behind and softened with a haze, as if the artist captured the stifling humidity of a Southern summer.

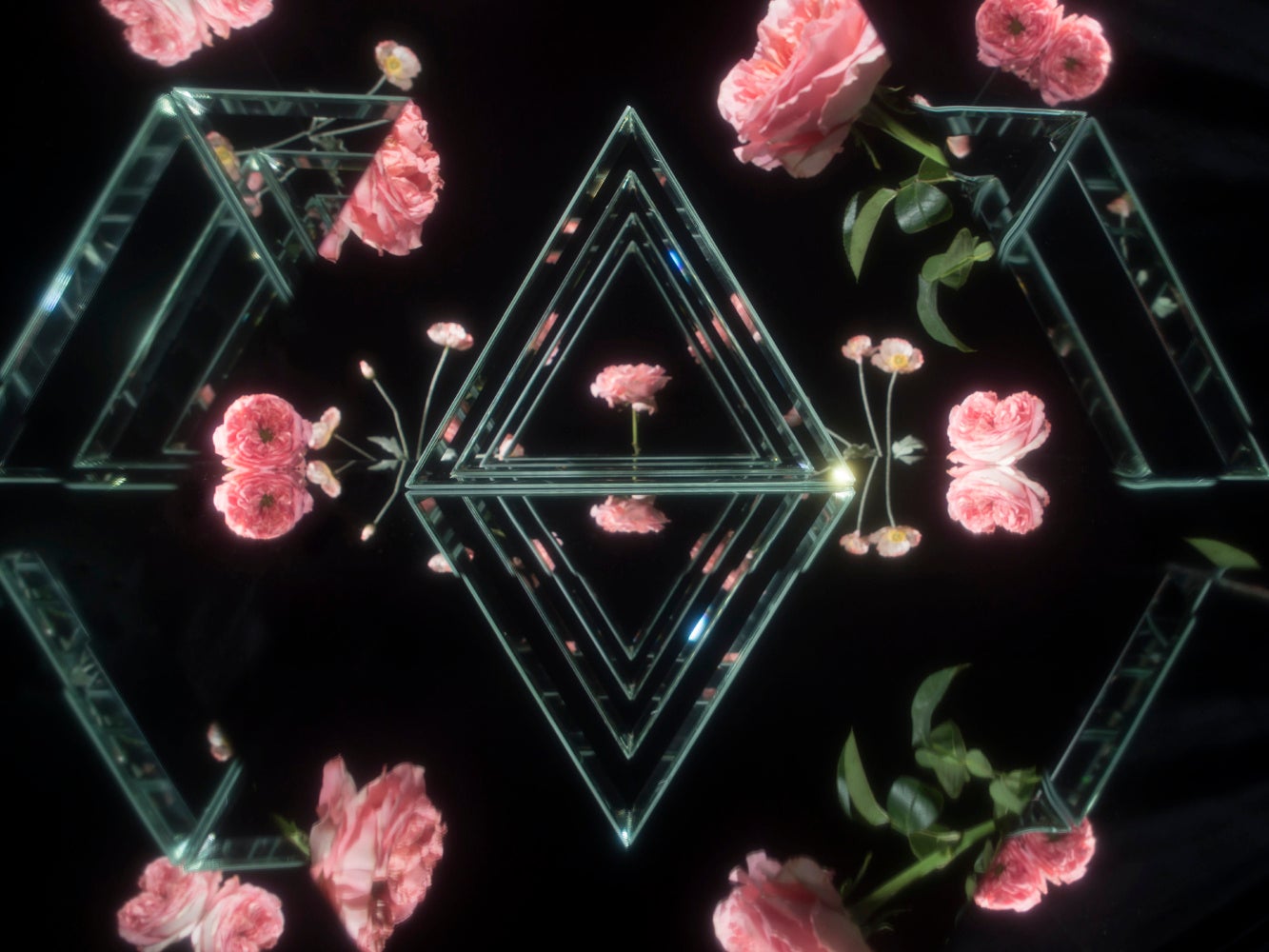

In Matrilineal lineage (my grandmother’s mother) (2025), for instance, three colossal pink triangles are stacked atop one another, emerging from a bright, tangled mess of twigs and wild grass. They tower over the foliage, thanks to the camera’s low angle. A reflective glint shines from where the triangles intersect, creating, entirely in-camera, the kind of sparkle effect you only see in a toothpaste ad.

Russell refers to these filters and effects as “pleasure stacking,” with each layer moving the image further from reality.[2] In the same way Old Hollywood’s cinematic tricks smoothed over and masked a star’s imperfections, Russell’s approach elevates his sometimes-makeshift constructions, making them look more mystical and otherworldly than they appear to the naked eye.

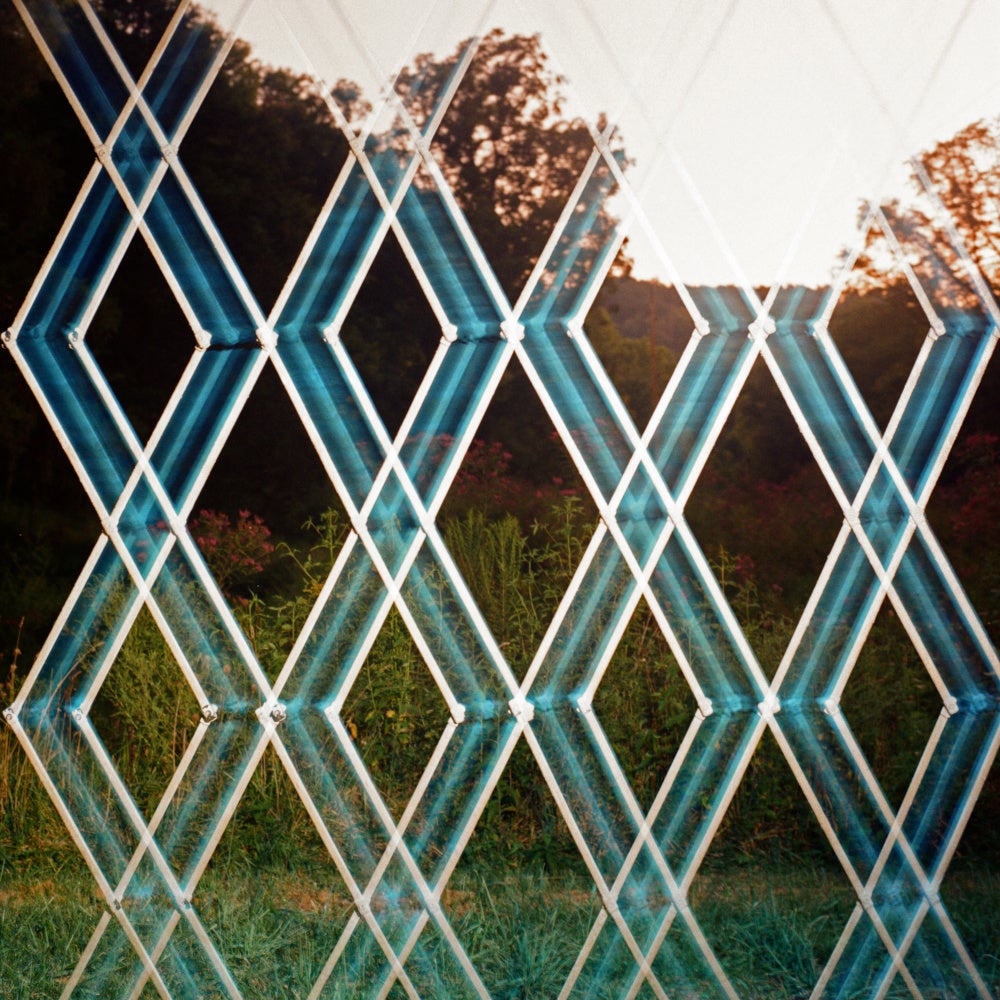

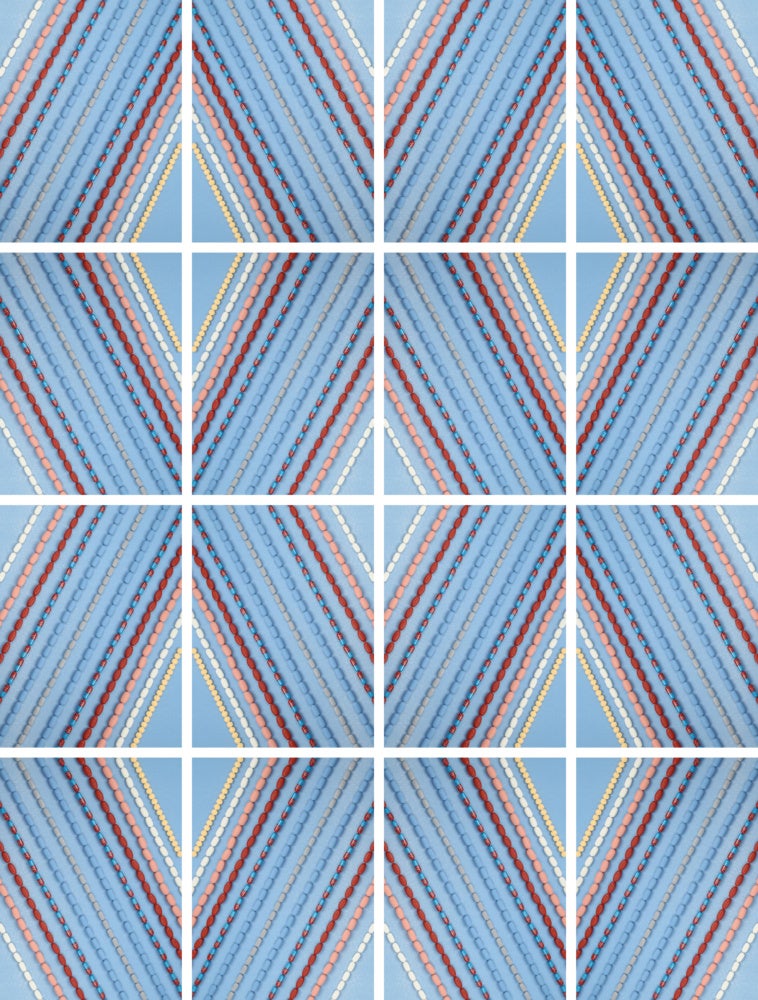

The photograph Light weaving (2025) features a hazy flash of a repeating white and blue diamond pattern—based on traditional Choctaw weaving and basketry designs that evoke the prevalent Eastern diamondback rattlesnake—overlaid onto a field at sunset. Slight motion blur suggests that the shapes have flittered across the depicted landscape, or flickered like a failing fluorescent shop light. At first glance, the photograph seems to be a double exposure, but in actuality, it is a single take using analog means: Russell created the glowing weaving pattern by shining studio lights onto old tent parts covered in reflective glass beads, the kind commonly used as highway markers.

“I might be an artist, but I was a redneck first,” Russell told me. He described how such homespun ingenuity led him to craft a rudimentary pulley system, or, in his words, a “wildass country contraption,” to make this image come to life.[3] He posted a video of the apparatus in action to Instagram; it’s as hilarious and lovably odd as it sounds, a reminder that underlying Russell’s poignant and poetic works is a strong sense of camp, play, and absurdity.

His upbringing partly explains these proclivities. He’s full of stories about his father’s rough-and-tumble resourcefulness, describing with reverence how his dad would throw together odds and ends to craft something spectacular. Once, his father built a fishing boat from scratch, bolting down sheets of plywood, lawn chairs, and a motor to a large slab of Styrofoam. Later on, he bought an old bread truck, determined to convert it into a livable RV for the family. In the winter months, his father would cover their home in thousands of Christmas lights, running them through a single cord that he would wire into the porch light, Russell recalled. “That man taught me everything I know, for better or worse.”[4]

That paternal influence can be seen in the unconventional materials Russell uses in his pieces. “My budget for art is $4, $8, or whatever is lying around,” he said, noting how the threefold goddess figure at the center of Matrilineal is made from reclaimed color gel guards that fit over industrial fluorescent bulbs. It’s the kind of low-cost décor and makeshift mood lighting used in the small-town gay bars that Russell remembers fondly. Matrilineal’s bright pink plastic cylinders were hung from a tree by Russell and a friend’s seven-year-old daughter using clear fishing line; the photograph was taken on medium-format film, with no post-production Photoshop involved.[5]

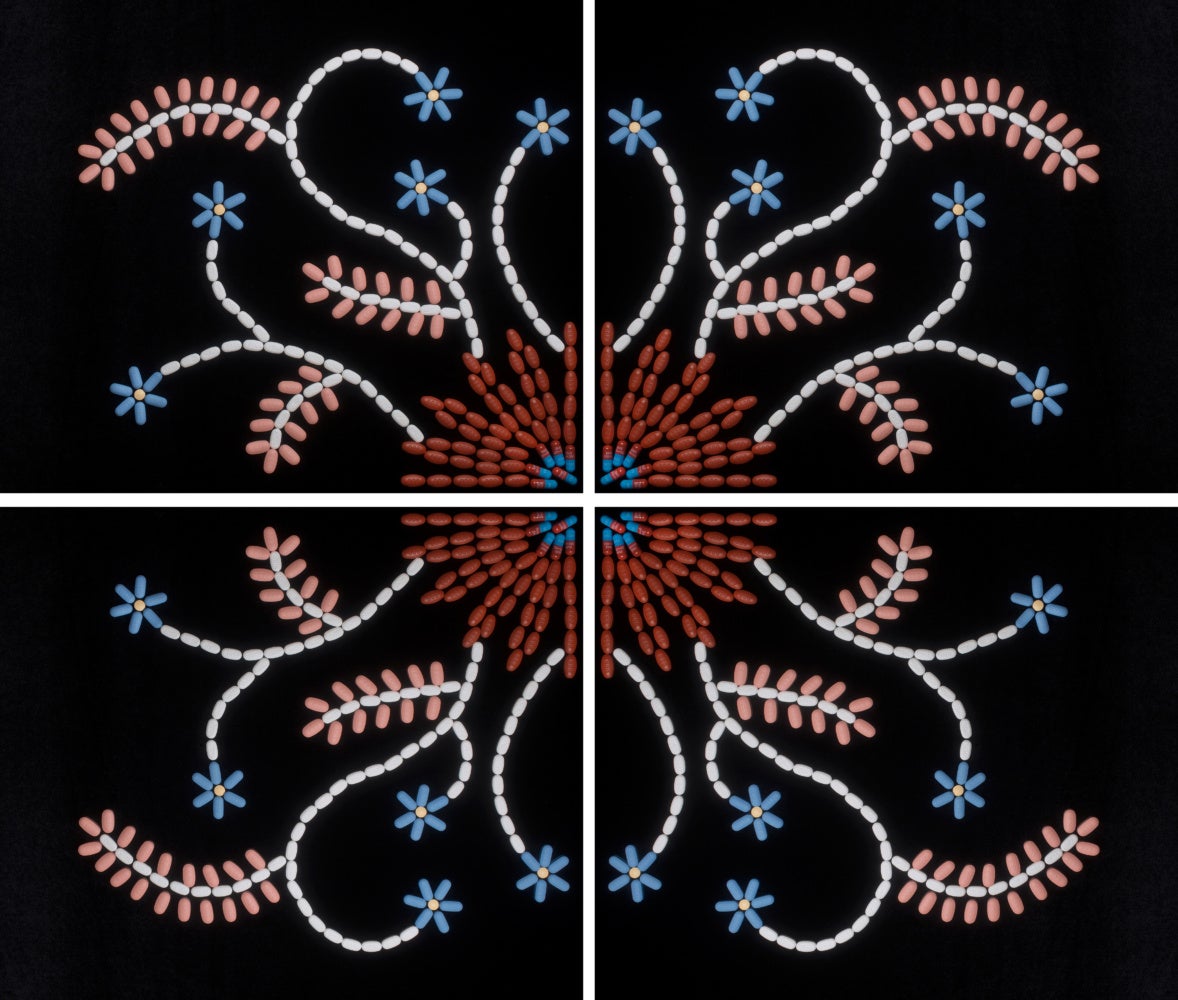

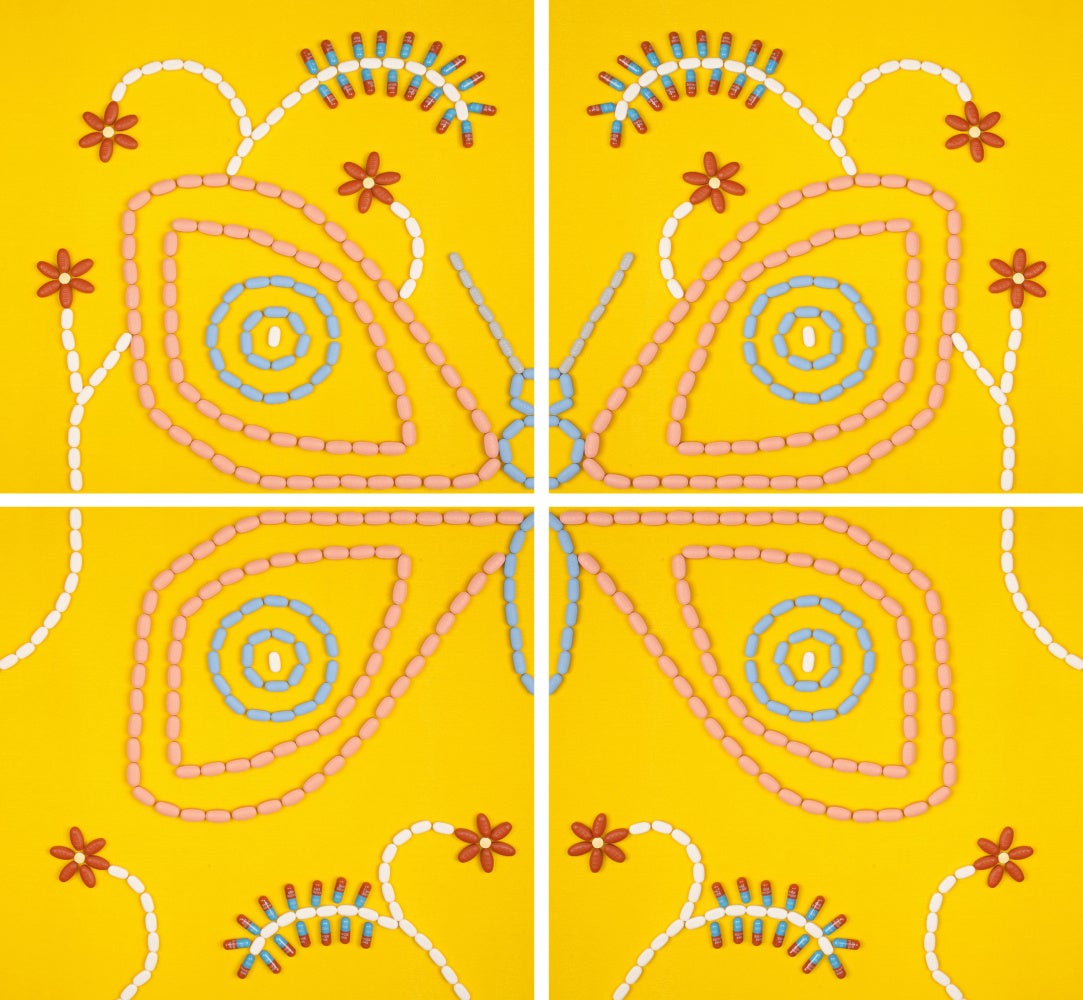

Under the gloss, the sparkle, the filters, the layers of pleasure, Russell’s works are deeply personal, working through private and generational trauma with illusion, grandiosity, and slapdash glamour. Works like Flower medicine (2025) and Diamond waves in the blue, blue light (2025) replicate ornate Choctaw embroidery patterns using a colorful array of the artist’s HIV medications, fashioning, quite literally, beauty from tribulation. The nineteen-foot-long There’s a Poem in my Garden (2025), printed on lush velvet and installed on a glowing pedestal that is viewable in the round, depicts hundreds of blossoming flowers set against a dark void. The blooms come from a plot that Russell cultivated after his husband, Sterling Kinsey, passed away in 2013. The work is thus a testament, a tribute, and a charged portrait of quotidian allure.

Nearly all of Russell’s photographs are taken at his pastoral home, located in an intentional queer community nestled in the woods of middle Tennessee. The scenery reminds him of the small Midwestern town where he grew up. The landscape, he says, sparks a renewed sense of experimentation and creative resourcefulness that enables him to create new art from earlier life lessons. For his latest series, Dark Big Bang, his most powerful and emotionally resonant body of work to date, Russell drew inspiration from the distant past, from the dawn of the universe, in an attempt to reveal a new way forward.

Russell, an enrolled member of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, was raised in Lindsay, Oklahoma, a small town in the neighboring Chickasaw Nation. “My family has been in this same little part of the Chickasaw reservation, literally the same county I grew up in, since they came off the Trail of Tears,” he said. Digging through his ancestral records, Russell learned that his family was initially allotted 1,300 acres of land in the Chickasaw Nation near Joy, Oklahoma; however, after the destructive and damaging Curtis Act of 1898—which sought to dismantle tribal governments and their concepts of communal land ownership in favor of privatization—non-Indigenous in-laws in Russell’s family took majority control of the lineage’s share.[6]

“everything was erased in my family”

“The land we were allotted didn’t stay in the family longer than ten to fifteen years before it was stolen or sold by white people,” he continued. Shortly after, his great-grandmother and grandmother were sent to the St. Agnes Academy, a forced-assimilation boarding school run by the Catholic Church. Driven by federal policies and operating for nearly 150 years, these schools aimed to erase Indigenous cultures and promote homogenization, with many children experiencing severe abuse, neglect, and even death under the pretense of reformation.[7] As a result, “everything was erased in my family,” Russell said. “All the history, all the culture, all the language, erased.”[8]

“I’ve had an Indigenous touchstone my whole life,” Russell told me. He recounted his childhood in the Chickasaw Nation, his high school years when he first showed his art at Oklahoma City’s Red Earth Festival, and, his early twenties, “raving on the rez.” However, since the details of his lineage and his family’s connections with wider Choctaw culture were almost completely lost, he said, “I’ve never made art that was hyper-specific about my personhood.”[9]

This change in Russell’s approach was prompted by a recent falling out with a few family members, both biological and chosen. “I wanted to uncover the root traumas that informed the actions and responses that led to all this turmoil,” he recounted, “whether it’s generational trauma, ancestral trauma, personal trauma, or whatever has happened to make someone react this way, myself included.”[10] What Russell soon uncovered, working with the Choctaw Nation to learn more about his heritage, was a family history marked by generations of anguish and stress.

Running parallel to Russell’s familial exploration was a burgeoning interest in quantum theory and astrophysics. “After the initial Big Bang released all matter into the universe, there was a second Big Bang that released all dark matter and dark energy,” he explained to me. The prevailing theory illustrates how “dark energy and dark matter make up the majority of the universe, but we can’t see it. We can’t measure it. . . . It affects everything that we do, but we don’t know how to point to it specifically.”[11]

Russell wove the corresponding threads of these concepts together for several recent pieces that examine the effects of the unforeseen on our own outlooks and attitudes. “I don’t necessarily make bodies of work—I make work while life is happening, and then, usually, that culminates in a specific period or an idea,” he said, noting how the works in Dark Big Bang developed organically.[12]

The polyptych photograph Anna (the gardener and the doctor) (2025), is another work that acts as a tender, allegorical portrait of someone who made a lasting impression on Russell. The image features a symbolic, embroidery-like arrangement of Russell’s HIV medications on four separate panels of velvet, created with Dr. Anna, Russell’s primary care physician, in mind. “Whenever I have an appointment, I’m just one of the patients living with HIV that she’s seeing that day,” Russell wrote. “She moves between the rooms, checking on everyone’s individual needs and well-being. This last year, while I was sitting in one of those rooms waiting on her, I imagined her like a butterfly floating around a garden checking on all of her flowers.”[13]

Russell’s evocative photographs convey tenderness and vulnerability, offering viewers a powerful emotional experience, even without the context that a backstory or explanatory wall label can provide. With the works in Dark Big Bang and other series, Russell crafts images that are meditative and celebratory, indicative of a queer futurism that’s firmly rooted in the rural. “A lot of the work, I like to say, is told from a future tense—like almost all these artifacts are from the future and we’re looking back on time,” he explained. “I take these moments of pain and create moments of joy, introspection, and hope out of them.”14

[1] Interview with the author, June 11, 2025.

[2] Interview with the author, June 11, 2025.

[3] Interview with the author, June 11, 2025.

[4] Interview with the author, June 11, 2025.

[5] Interview with the author, June 11, 2025.

[6] M. Kaye Tatro, “Curtis Act (1898),” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry?entry=CU006.

[7] Zach Levitt, Yulia Parshina-Kottas, Simon Romero, and Tim Wallace, “‘War Against the Children’,” New York Times, August 30, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2023/08/30/us/native-american-boarding-schools.html.

[8] Interview with the author, June 11, 2025.

[9] Interview with the author, June 11, 2025.

[10] Interview with the author, June 11, 2025.

[11] Interview with the author, June 11, 2025.

[12] Interview with the author, June 11, 2025.

[13] Benjy Russell (@benjyrussellphotos), “Anna (the gardener and the doctor), 2025 . . . ,” Instagram post, June 16, 2025, https://www.instagram.com/p/DK9ysEiuQM_/?img_index=1.

[14] Interview with the author, June 11, 2025.