On August 29th, I convened a small group online to reflect upon and attempt to map language learning as multilingual folks from or living in the South. “Mapping language learning,” while perhaps a bit vague, emerges from the following questions: How have spaces of language learning, both physical and beyond, shaped our perceptions of the South? What power lies in collective memories, and how might we proceed in our dreaming and solidarity from this kind of reflection? Approaching the act of mapping as a process that can inflict and unravel harm, but also provides an opportunity to consider the genealogies and futures of living together.

I planned the session thinking of my particular inheritances of language—of my mother’s Beijing accent, my father’s Hunan dialect, and the myriad Englishes I have grown up hearing and speaking. My father is from a village in Hunan, a rural province of China. There, the dialects spoken are hyperlocal, and the rural regions of China, like in the United States, are often perceived as backward and uneducated. Though I was not raised to speak my father’s dialect, my attempts to draw connections and make observations about the southern Chinese dialect in relation to the standard Mandarin which I have been formally taught has allowed me to recalibrate a sense of home and the world. There are similarly hyperlocal and specific dialects in the South that are likewise relegated to an inferior status to a “standard” English. I think of my voice and my friends’ voices when I speak English, and the ways Asian Americans in the US South interpolate and formulate their identities, existing as both perpetual foreigners in the US and anomalies in the South. The politicization of non-standard dialects both in China and in the US works to uproot and displace one’s sense of home, of belonging. The motherland remains out of grasp.

When I am asked “where are you really from?” I register that someone is attempting to place a cultural frame around me. They are saying, you are here now. Where were you before? When aunties and uncles ask me “where are your parents from?” they grasp for kin. Of course, they respond with a knowing nod when I tell them my mother is from Beijing, usually an intrigued nod when I share my father is from Hunan. We grasp for kin or categories. We size each other up.

Leading up to the event, I invited participants to prepare to share, “a word or saying you remember learning in your life and the memory that surrounds that word or saying” during introductions. Our maps of language learning felt latent, palimpsest-like in these small stories we passed around. In childhood, one attendee heard the Chinese adjective 无聊 “wu liao” used to describe them by a parent, and without knowing the exact meaning, assumed it translated to “annoying.” Carrying such an understanding of the term for years, he later found that in fact 无聊 translates closer to “bored” or “silly.” Another shared that since moving to New York from Georgia over the summer, he began to use the word “deadass” when speaking. Another shared that she had been using the phrase “I’m dead” when she found something funny. Following her, an attendee who grew up in Texas and Virginia shared Audre Lorde’s “your silence will not protect you” as a quote that came to mind. Another fellow Texan with Colombian citizenship shared a quote that was printed in his elementary school’s weekly parent newsletter that he’d cut out and tape onto his door. The quote was, “As I grow older, I find that the things I regret doing are the things I didn’t do.”

All too familiar with the uneasiness that set in during art time in elementary and middle school when our classes turned immediately to making things after receiving brief instructions, I set aside about half an hour of time after introductions for us to reflect and read before moving to pen/paper. I compiled and shared a document with written selections from Adrienne Rich, Homi Bhabha, Ocean Vuong, and coincidentally, Audre Lorde for us to think with; Lorde’s piece included the very quote my friend brought up.

Lorde writes the adage on the false safety of one’s silence in her essay “The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action” upon coming face to face with her mortality, when she must undergo surgery to remove a potentially malignant tumor in her breast. She asks, “what are the words you do not yet have? What do you need to say? What are the tyrannies you swallow day by day and attempt to make your own, until you will sicken and die of them, still in silence?” Lorde affirms that denying ourselves what we need to express proves fatal and that what we need to say renders most clearly when we must confront death. Several stories and the words/phrases shared during introductions seemed to orbit silence and death, too. As we discussed our language maps, our stories moved around humor and lightness, and soon enough, we came upon death.

As we discussed the when’s & where’s of silences (in English, in another language), giggles and mourning both bubbled up to the surface. The excerpt from Ocean Vuong’s On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous recounts the narrator, Little Dog, attempting to help his mother purchase oxtail, standing in shame-filled silence after watching her mime the tail of an ox for a laughing butcher, unable to translate from Vietnamese. The attendee from Colombia and Texas noted how the story prompted reflection on his mother’s approach to engaging with both non-native and native English speakers—“hacerse entender,” “to make yourself understood.” He emphasized “make” as in “make it work” to refer to an objective of a game of charades. Another spent time reflecting on Lorde’s essay, and she wondered aloud why it always seems to take death to speak praise or to be truly honest.

In an email exchange prior to the language mapping event, a friend shared:

“I’ll say I’ve never thought of myself as ‘southern,’ and I think very few of my close friends would either [regardless of race]. I think that’s definitely because we all grew up in Atlanta. I will say though that even if I think there was a basis for me identifying as “Southern” I probably wouldn’t want to. I don’t think there’s anything that great about the South. Some of my friends will use ‘y’all.’ I usually say ‘you guys.’ I do sometimes feel like I’m making a conscious effort to not say ‘y’all.’ I don’t think I’ve ever consciously thought of myself as part of the ‘Asian American community,’ especially when this community is understood to be a part of today’s identity politics culture etc. I.e. I don’t think I’ve ever felt proud to be Asian American, but I’ve also never felt ashamed. But I certainly am part of some nebulous concept of the Asian American community.”

The idea to bring together the language mapping group was partly inspired by conversations with Atlanta-based artist and freelance translator Jenny Jisun Kim. Delighted by the dual practices of language translation and visual art, I asked about her work and her relationship to place. She began by sharing her experience with language as a child:

“I grew up as an ‘international kid,’ moving from country to country every few years. Naturally, I developed a strong instinct for survival, especially in relation to speaking ‘the language.’ I thought that language (most often in the form of spoken language) determined the fitness of someone or became a measure for rapport/affinity (whether or not you belong) […] On the other hand, place (as in the geographical location) became less and less relevant to how I understood the language spoken there. Maybe I am more interested in placeness, as in the quality of being a place, or a space with meaning.”

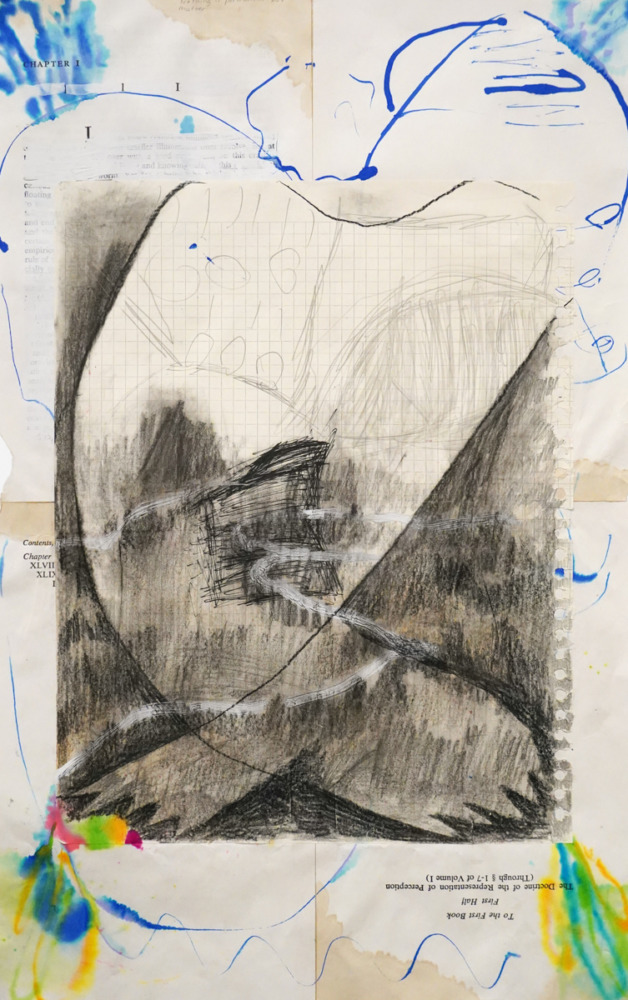

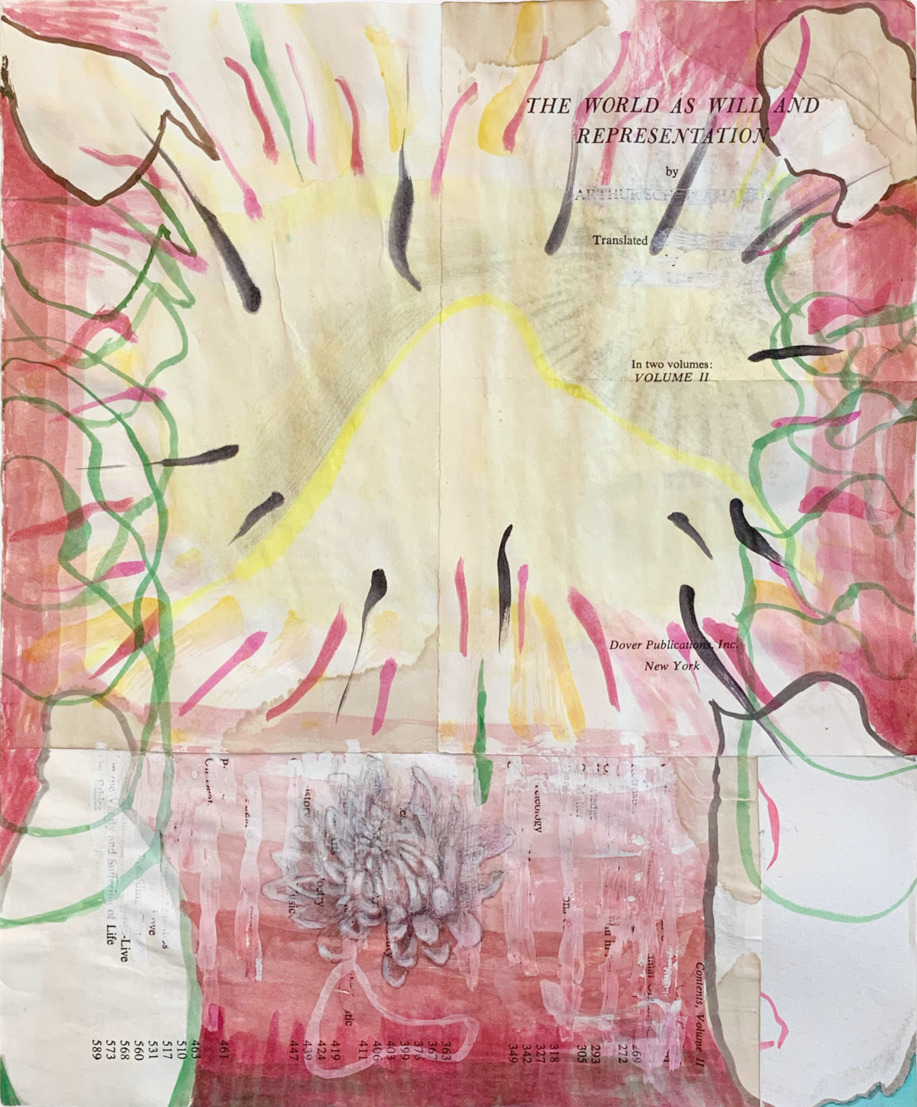

In her 2020 painting, Mother Tongue II, exclamatory brushstrokes float near/over the title page of Schopenhauer’s The World as Will and Representation which has been collaged onto the canvas. Kim approaches Mother Tongue II almost as a trickster, deftly weaving in several “tongues” of philosophy, English, German, and Korean into a capacious and vibrant web. We wonder what has become of the original German text, translated into English, divorced from its binding and intellectual milieu, decontextualized two, three times over. Kim leaves us to read or not read the various elements: from the bright starburst at the painting’s center to the shapes in all four corners, to the realistically rendered flower that obliquely opposes Schopenhauer’s title. The possibility for manifold understanding demonstrates Kim’s perception of her role as the artist and translator. Indeed, Kim described herself at play “with signification and difference in interpretation” in the image of a white chrysanthemum. She shared, “white chrysanthemums are frequently used in funerals, hence signifying death or emptiness in Korea; but this is an association lost in many viewers outside [of Korea].” Kim’s nod to an association in Korean culture through the white chrysanthemum also prompts us to consider literacies and languages beyond what is spoken.

Kim sees that her art is about “observing how meaning is generated.” Hosting the language mapping workshop, I also felt observation was my aim. Yet, I wondered how Kim mediated desire in her work both as an artist and translator, employing silences and pockets of illegibility in her art while slowing, observing.

The language mapping workshop then moved to dedicated time to translate our reflections to the visual. As I worked on my own map, I thought about my memories of attending Chinese language school on the weekends. I thought of my Chinese school at the Atlanta Chinese Christian Church and then in local middle school. I can picture one of the teachers at the front of the classroom, an auntie with hair like my mother’s, her silvery roots outpacing her black box-dye jobs instead of the mostly white women who taught at the school by day. I was struck by the duality between a public school also functioning as a private space to practice mother tongues.

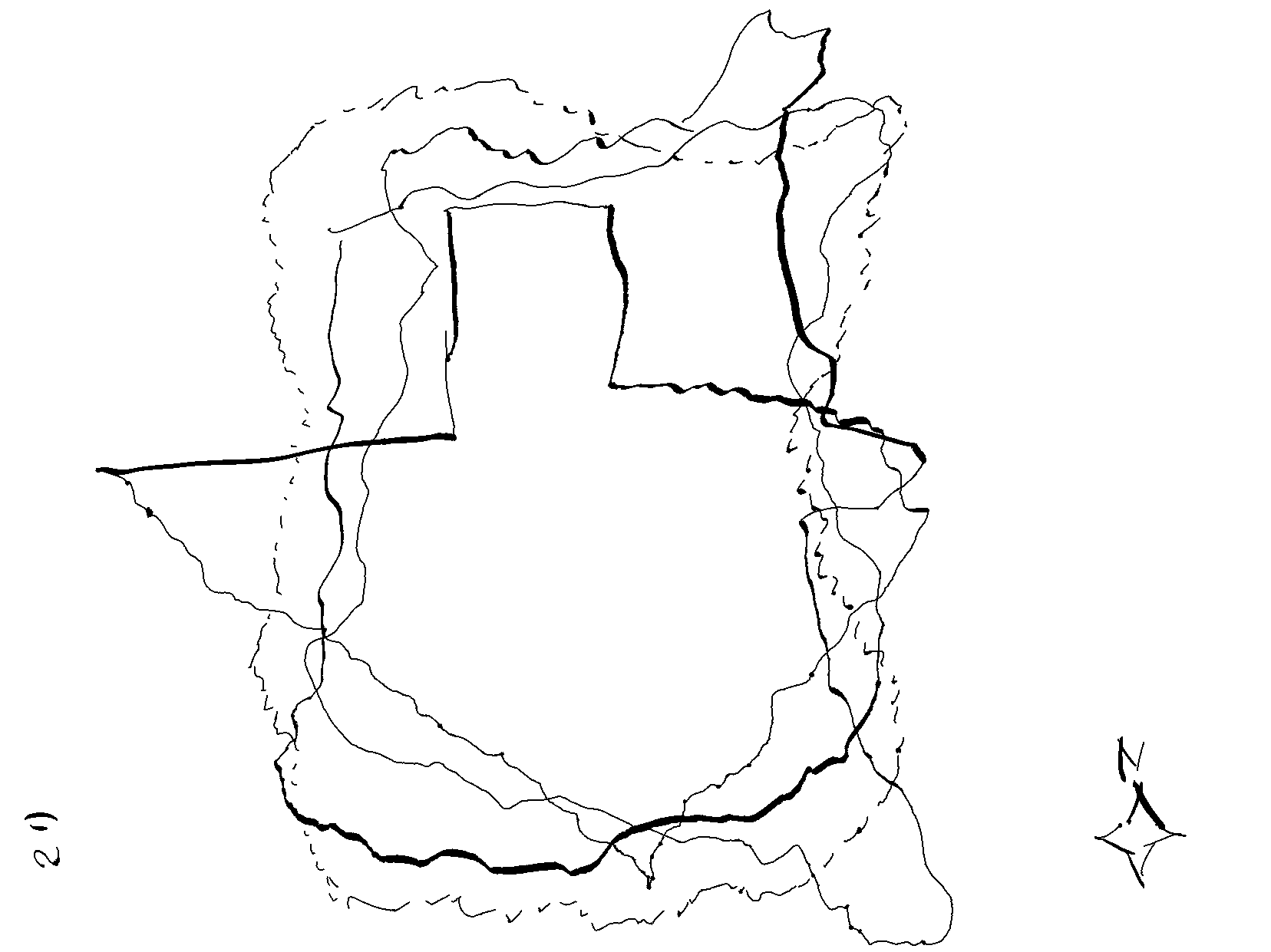

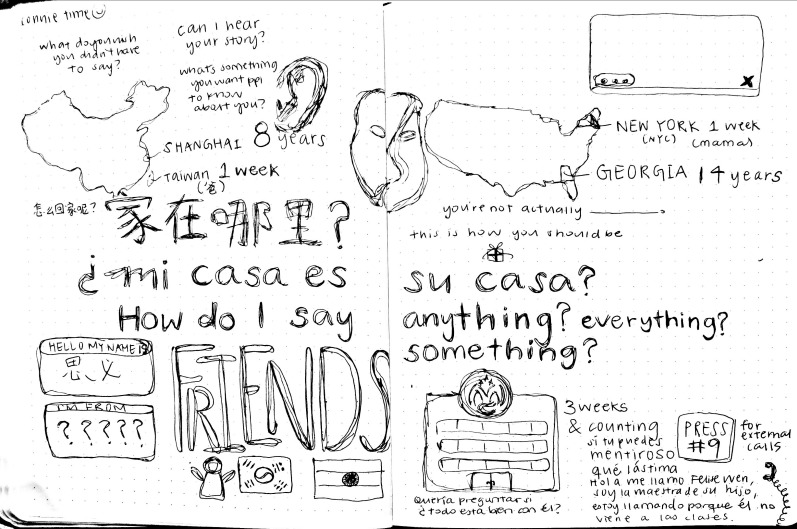

Our responses trickled in. Héctor shared two pieces, describing them as “a map of the different places whose languages I had grown up with (Colombia, France, Texas and USA)/a collection of amorphous blobs” and, “an attempt at synthesizing those associations (in relation to place and language) into a term: mother tongue.” He reflected, “Amorphous blobs keep the ‘language mapping’ from becoming some sort of key to definitive self-discovery. A ‘mother tongue’ may grant a momentary feeling of being a poet but is ultimately still limited like any other language in a way that is made more obvious by living in a non-mother tongue.” One of the attendees shared a visualization of her family’s time living in New York, Georgia, China, and Taiwan. Her questions face us prominently: “家在哪里?” “How do I say anything? Everything? Something?”

Our resulting maps and diagrams of language learning unearthed more to delight in, questions and reflections to carry. The regional borders of the US are not of concern—we get mapped across geopolitical ones. Yet, we turned toward the question again in order to bear witness to ourselves and one another. Not only does language connect us to a place, language describes a relationship to a place and to one another. Our collective processing points to literacies beyond spoken language, as well as a folding-in of space and place that impacts the delineation of cultural boundaries. As we witness ourselves and each other in the continual process of learning and acquiring language, we dream of transforming our relationship to silence, moving to solidarity and critical awareness.

This essay is part of Burnaway’s yearlong series Word of Mouth.

Find out more about the three themes guiding the magazine’s publishing activities for the remainder of 2021 here.