Nowhere is cultural life unaffected by the shadows of forgotten ancestors. Many forebears are not known because their lives went unrecorded; some go ignored because their record rouses shame. For years I spared no thought for the Confederate officer’s sword that dressed the mantle of my childhood home. I knew this relic belonged to my mother’s pedigree, and I remember being told that the sword was ceremonial, mainly serving as a prop—like the artifact survived untarnished by history. My ignorance of this ancestor haunted me more than confronting his ghost. Last year I finally read the diary of the man the sword belonged to until his untimely death from measles. Though it was uneasy, the experience led to a transformative recognition when I began imagining what my patrilineal descent from Ashkenazi Jews might have meant to this Texan forefather who journaled about joining a “holy mission by driving the invader from the soil in which he desecrates and pollutes.” I felt proud of my own life as the redress to his impoverished sense of poetry.

The art of living with the dead entails observance not only of one’s personal ancestors but the multitudes of history borne through cultural traditions. In his introduction to the exhibition Supernatural America, curator Robert Cozzolino writes: “We live in a nation in which forgetting the traumas that enabled its existence is a daily way of life, but one that is untenable… To remember is to confront ghosts, to ask what they want, to make amends, and to learn to live with them.”1

Besides manifesting in the haunting psychology of loss, ghostly presence pervades objects of everyday existence. Social theorist Avery Gordon maintains that “ghosts are real, that is to say, that they produce material effects. To impute a kind of objectivity to ghosts implies that, from certain standpoints, the dialectics of visibility and invisibility involve a constant negotiation between what can be seen and what is in the shadows.”2 From action-based practice to sculpture, printmaking, and film, Texas-based artist Dario Robleto has mediated between remote, almost unbelievable apparitions in the history of war, popular music, space exploration, cardiology, and the science of dreaming. Robleto’s body of work is a testament of care for the materiality of ghosts.

The alloy of debris and pieces in Robleto’s sculptures—as diverse as antique pain bullets, residue from tears of mourning, a million-year-old blossom, desert glass produced by the first atomic blast—create a material poetry sublime and astounding to the imagination. No One Has A Monopoly Over Sorrow (2005) features men’s bullet-lead-coated finger bones resting tenderly within a basket of preserved bouquets and hair flowers made by widows of the Civil War. “This piece will always have a special connection to me because I felt I had to change if I was going to do it,” the artist acknowledged. “It raised in me a question that I still use today and that has become a guiding principle for all my work which is, ‘What do I need to do to earn the respect of this material and story?’” The art of living with the dead, Robleto affirms, calls for the broadening of one’s boundaries regarding responsibility and care. That mediation must be extra-sensitive to ghostly matters, as practiced by the artist who vows: “If I do not feel I have earned this respect then I will not proceed.”3

In a body of work focused on Civil War-era mourning practices, irreplaceable artifacts are rendered unrecognizable by recombination with real human remains. “If you are going to talk about war in any serious and respectful way,” Robleto reflected, “I feel you cannot blink or look away from the actual realities of the battlefield. And one of those realities is that the destruction of the body and the mind can be so devastatingly complete that only dust is left.4 Pondering what is lost in the alchemical process of change, viewers are led by Robleto’s work through a structure of feeling—a theory, even, of ghosts: that conscious acceptance of destruction is necessary to have a positive “relationship with the dead: unity with them because we, like them, are the victims of the same condition and the same disappointed hope.”5 Yet, far from embracing cynicism with the inevitability of decay, Robleto champions the promise of sensuous knowledge by memorializing the interconnectedness of all things enduring as particulate matter.

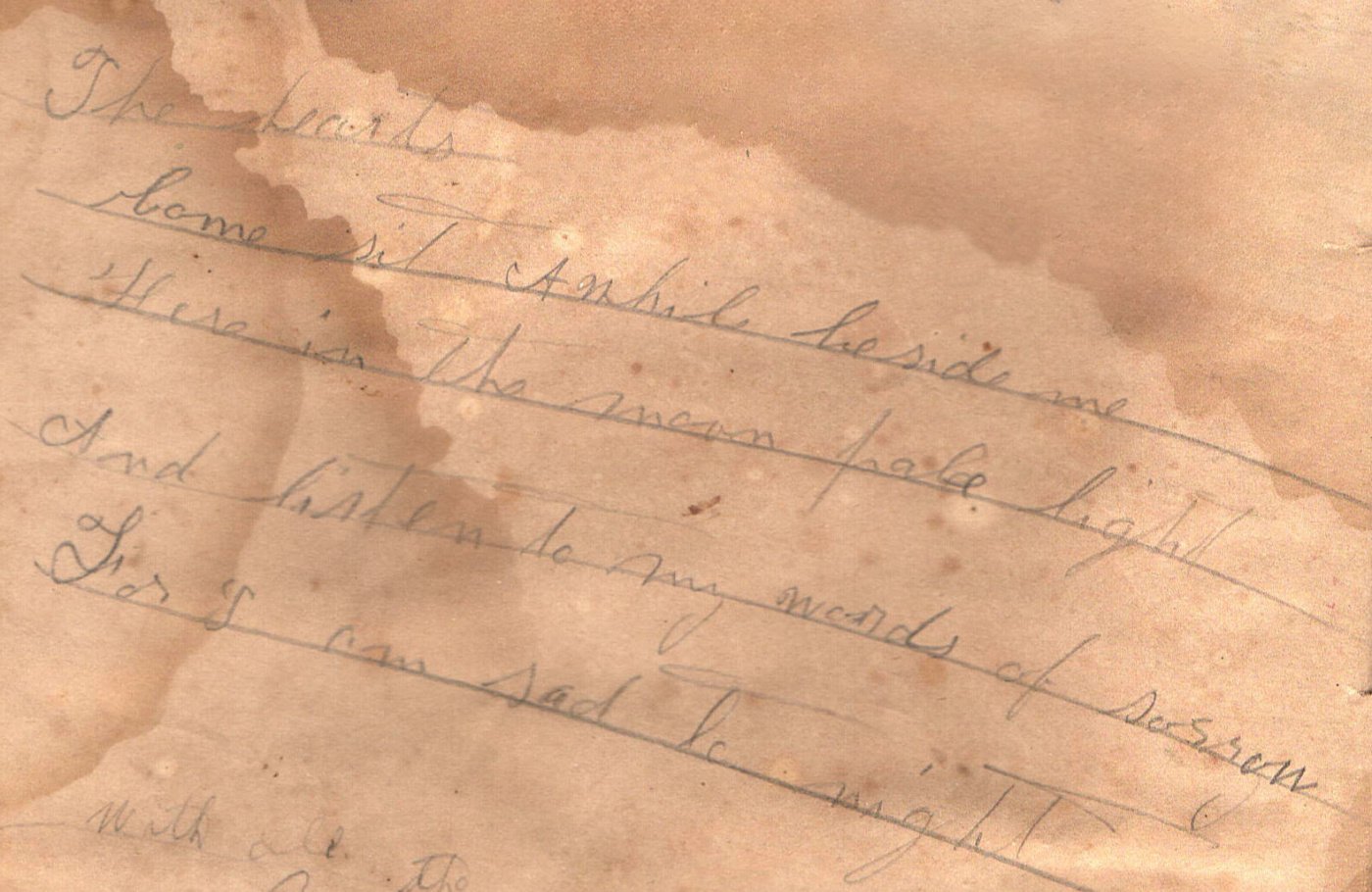

Daughters Of Wounds And Relics (2006) features a long braid of thick black hair on a silk pad reminiscent of an antiquated pantyliner. Made of individual strands of stretched audiotape, the braid literally weaves together recordings of the last known Union soldier’s voice with the voice of the last known Confederate widow. Indiscernibly present in the piece as paper-pulp ribbons and trimmings are sweetheart letters written by soldiers who did not return from war. Not only the selection of materials, but the artist’s resurrection of nineteenth-century handicraft conjures the spirits of women in mourning. Embroidery and hairwork represent the culmination of anonymous labors performed inside the home, which Robleto regards as suffused with presence and having significance to the soul. Returning to material practices on the verge of extinction, his artistic mediation draws attention to ghostly residue in craft traditions.

From Robleto’s work I learned that any object which inspires remarkable subtleties of feeling is itself a source of paranormal activity. One such object, A Phantom Attempts To Sing As She Once Did On Earth (2004) contains reel-to-reel audio of a female ghost from Gettysburg humming a lullaby within a transhistorical soundscape of soldiers at war. It is composed of a mix of white noise recorded at various battlefields on dates of reenactments, in which haunting, inexplicable sounds of shooting, yelling, dying, and self-soothing were detected on tape. Electronic voice phenomena (E.V.P.) are typically associated with ghost hunters, who search static for signals that could be interpreted as spirit communication. Spooled into a cassette made of de-carbonized human bone dust, melted bullet lead, and rust, A Phantom is too fragile for playback: she can only attempt to sing. Robleto sets the tone for what cannot be heard by manually stressing the object’s worn wood case and verdigris corrosion. The work is fully, finally realized as a materialization of spirit in sympathetic objecthood through the medium of the wall text or label—its material poetry, in the artist’s words.

Writing about supernatural currents in late-nineteenth-century American life, historian Molly McGarry describes how communing with ghosts affirmed “the possibility of disembodiment and a kind of purifying transfiguration and release from the earthly, gendered body.”6 A number of Robleto’s works seem interested in offering this kind of transfiguration to the memories of departed pop stars and divas. One sculpture—formally resembling a scuffed gadget in a paranormal museum—represents a vintage flight recorder made from melted Dusty Springfield vinyls, concrete, and an anonymous ‘voice retrieved from the wreckage.’ Robleto summons the singer’s intensely private spirit in an impenetrable-looking black box, as if it were fashioned to keep her secrets safe forever. From the perspective of the dead, there may be no deliverance from the human condition as rewarding as finding a non-mortal home in an enduring work of art. The aura of artwork elicits devotion from the living.

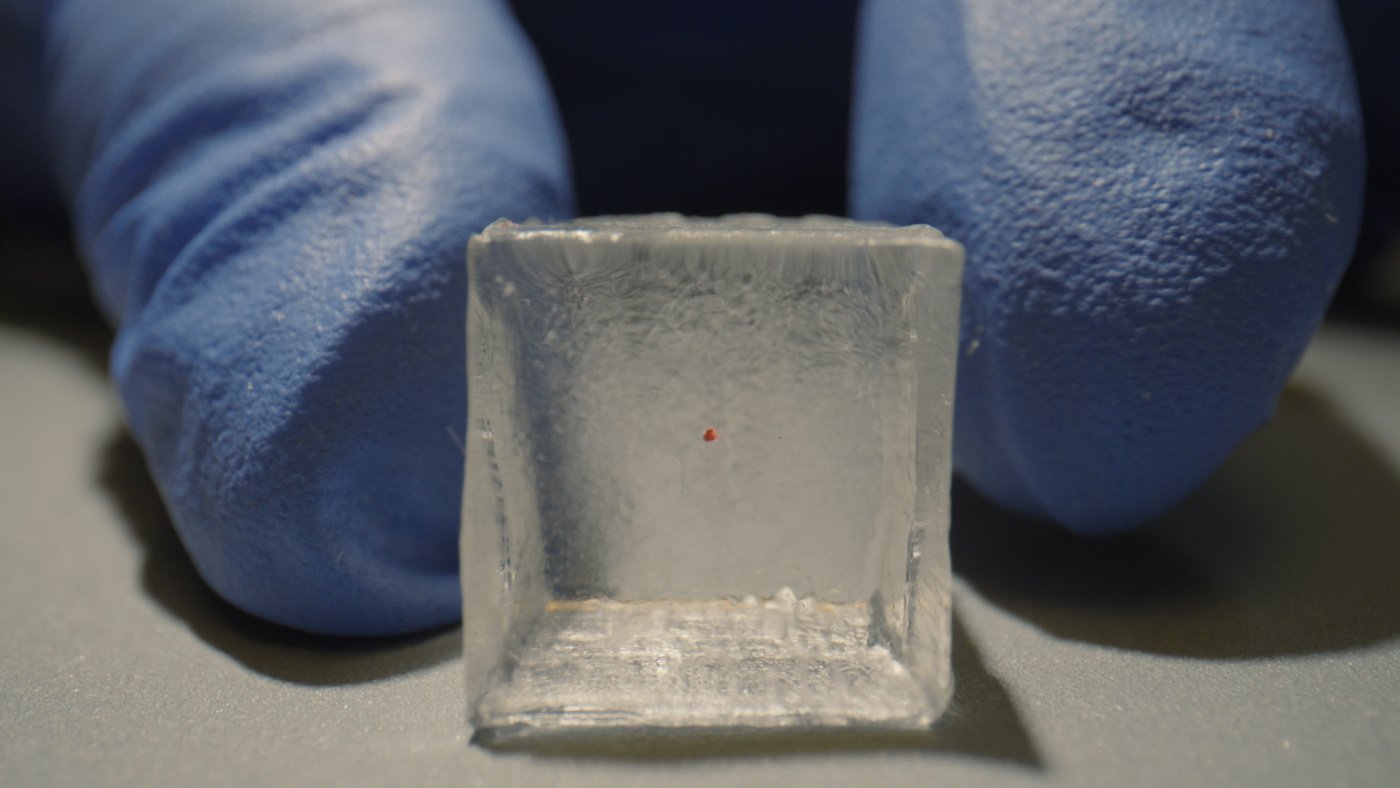

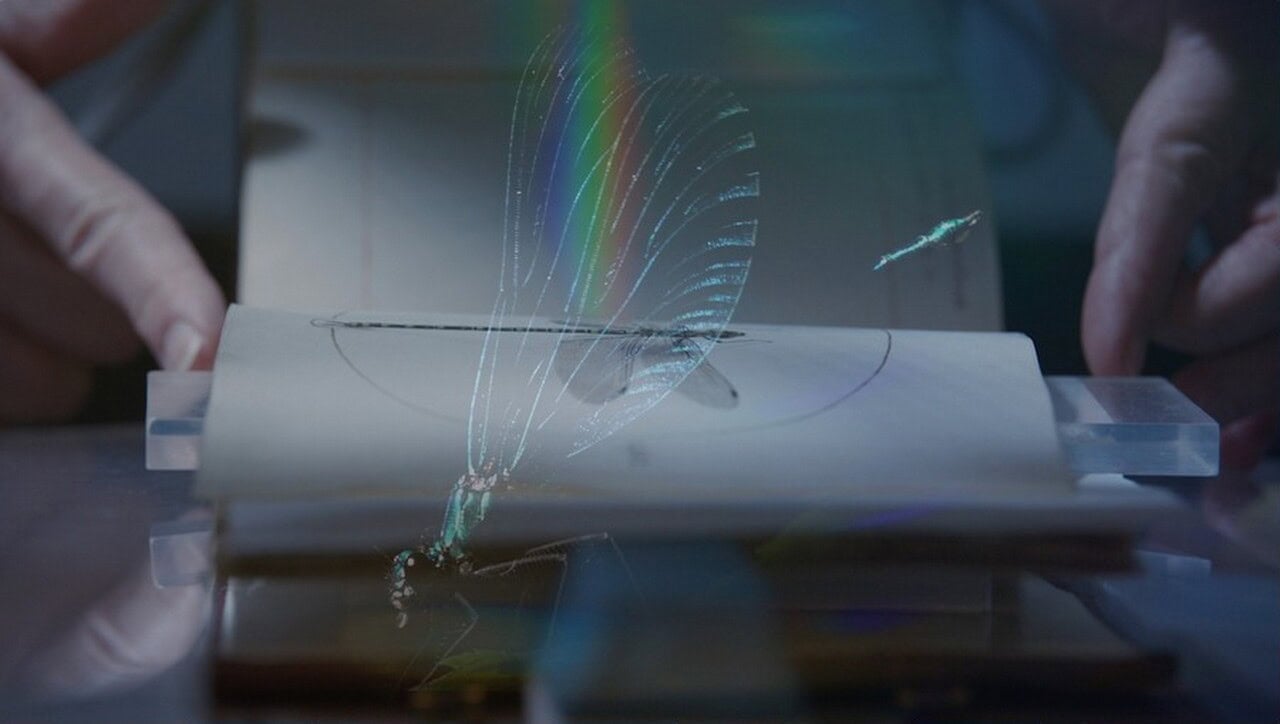

In Until We Are Forged: Hymns for the Elements (2023-2025), Robleto finds an ethics of care for the dead expressed by art conservators, “stewards to a history of tenderness; keepers of a covenant of memory” though they “do not know who will find the love they left behind.” The film follows conservators and scientists at the National Gallery as they devise ever-more sensitive methods for handling, documenting, and restoring the spirit of objects. A sequence which moved me to tears shows a conservator extracting a minuscule flake of red pigment from the shadow of an hourglass in Jan van Kessel’s Vanitas Still Life (c. 1665), embedding the flake in resin and hand-polishing it into a perfectly even, transparent cube, to be scanned and chemically analyzed for signs of inanimate life. Her work is anonymous, exceptionally skilled and conscientious of ruination. Robleto’s film identifies with the respect for the dead materialized as cultural property in the practice of conservation, “a logic of love so nuanced that each molecule matters. Each refinement, each analysis, and each repair carries an oath” of careful attention to ghostly effects.

For survival does not lie in the heavens, as expressed by Dario Robleto: the art of living with the dead begins with material recognition.

The logic of love and remembrance is a natural subject for the artist whose work has molded so much dust into exquisite memento mori. The question that has inspired Robleto’s decades-long exploration of mourning concerns the purpose of art, not excluding its moral dimension: what is the artist’s obligation in confronting incredible loss? While each generation reacts uniquely according to the spirit of their time, Robleto maintains that the common response to bereavement is creativity. Across disciplines and multiple media, his artistic practice models care for ghostly matters by transforming incomprehensible remains into works profoundly meaningful and curious to the imagination. For survival does not lie in the heavens, as expressed by Dario Robleto: the art of living with the dead begins with material recognition.

Single-channel UHD video, color, 5.1 surround sound, 43 minutes.

1. Robert Cozzolino, “Introduction: America is Haunted” in Supernatural America: The Paranormal in American Art (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2021), 13.

2. Avery Gordon, Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008), 17.

3. “The Civil War and American Art: Six Questions for ‘Materialist Poet’ Dario Robleto.” Smithsonian American Art Museum, March 12, 2013. <https://americanart.si.edu/blog/eye-level/2013/12/635/civil-war-and-american-art-six-questions-materialist-poet-dario-robleto.>

4. Ibid.

5. Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno, “On The Theory of Ghosts” in Dialectic of Enlightenment [1944], trans. John Cumming (New York: Continuum, 1987), 215.

6. Molly McGarry, Ghosts of Futures Past: Spiritualism and the Cultural Politics of Nineteenth-Century America (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2001), 85.