In our new feature Take Five, Burnaway will highlight five artists we’re excited about who are working in the South or are from the region. The first edition of this series focuses on artists working in the medium that created the visual imaginary of the South: photography. From Walker Evan’s FSA-funded work in Hale County, Alabama, to William Eggleston’s pioneering work in color photography and Gordon Park’s landmark photo essay “Segregation Story,” the South has long been the site of some of the most iconic and groundbreaking American photography. Unsurprisingly, contemporary Southern artists are exploring the medium in both inventive and classic ways.

Lucas Blalock

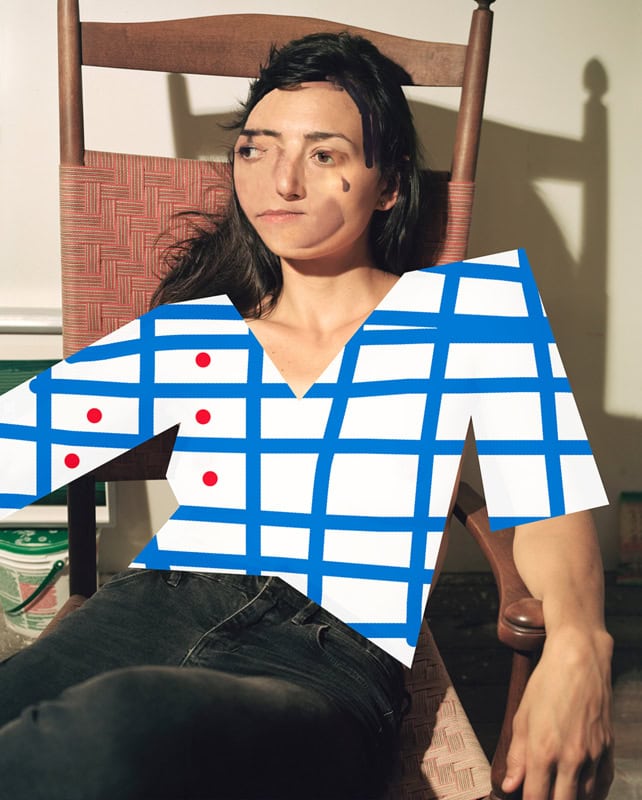

2019 has been a blockbuster year for artist Lucas Blalock, a North Carolina native whose first solo museum show—An Enormous Oar at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles—closed earlier this month, and whose work is also included in the current Whitney Biennial curated by Rujeko Hockley and Jane Panetta. In many ways, Blalock’s photographic projects reflect the tools of (and, sometimes, uncannily resemble) the images created by anyone with an iPhone or Instagram: filters, Photoshop, manipulated levels of saturation. Beyond these technical flourishes, “[the] making of the work has a lot more to do with a kind of idiosyncratic relational empathy,” Blalock told Photograph magazine earlier this year. “There’s a lot of humor, a lot of melancholy, a lot of body issues.”

— Logan Lockner

Diego Camposeco

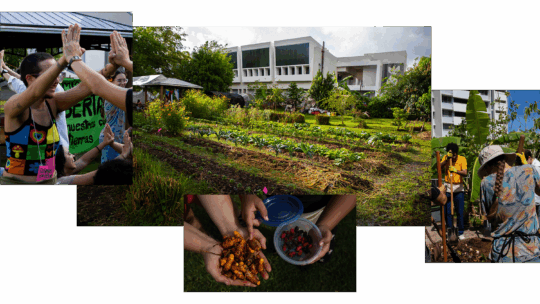

At the point of his untimely death earlier this year, North Carolina-based photographer Diego Camposeco was—at least by my estimation—one of the most exciting, promising young artists working in and—importantly—making work about the South. The son of Mexican immigrants to North Carolina and a 2015 graduate of UNC Chapel Hill, Diego was interested in using photography to depict the presence of Latinx communities across the American South. As he wrote in an essay for this magazine last year, Diego believed that documentary photography has a unique, powerful history and immense potential within the context of the American and Global South. His own approach to documentary photography contains wry, humorous inflections, showing subtly layered arrangements and references to Mexican culture, religion, and art history—an expansive, self-reflective, slightly meta visual and conceptual vocabulary.

— Logan Lockner

Sarah Hobbs

Georgia-based artist Sarah Hobbs uses photography as a portal into a world of methodical installation-making: she arranges and tacks panties on a bedroom wall, sculpts with twee butterfly sticky notes, and engineers meticulous domestic spaces. Although Hobbs has been an important figure in the Atlanta scene for decades, her work has also been widely collected nationally and can be found in major museum collections such as LACMA and the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago. In a moment wrought with conspiracy theorists, doomsday preppers, and a ubiquitous blanket of political anxiety over the American consciousness, Hobbs’s work feels like the domestic alternative to the hypervigilant, obsessive reality we are all one cataclysm from living within.

As BA contributor Claire Dempster described in her review of Hobbs’s solo exhibition in Atlanta earlier this year: “While there are no iPhones, computers, or contemporary technology that might more overtly symbolize the invasion of societal unrest into the domestic sphere, present concerns creep in, disrupting the interior tranquility. Plastic trees, nonperishable food, a living room set of inflatable furnitureb and sandbags preparing for a flood hint at the very real, underlying ecological future that no hibernation, act of salvage, or portal to another dimension can really keep at bay.“

— Erin Jane Nelson

Maury Gortemiller

Recently included in the Ogden Museum’s survey New Southern Photography, Atlanta-based photographer Maury Gortemiller’s work channels the region’s most iconic aesthetic: the Southern Gothic. Ripe with everyday materials transmuted into simple yet magical compositions, Gortemiller’s eerie images and scriptural titles suggest his childhood fascination with the Bible. It’s easy to imagine his dark, strange photographs with their spiritual nods and symbolism illustrating a Faulkner novel, or conjuring the spirit of Clarence John Laughlin. Nonetheless, his photographs also address the present moment, such as in Fan Diptych, in which images of faces digitally projected onto suburban ceiling fans transform banal digital portraits into alarming monsters.

— Erin Jane Nelson

Jared Soares

Currently based in Washington, D.C., Jared Soares first received attention in 2012 for his earnest and intimate portraits of aspiring rappers in Roanoke, Virginia. Since then, he has gone on to primarily document the cultural connective tissues of communities of color, both for personal and commercial clients. In one of these recent collaborations, Soares documented the town of Nicodemus, Kansas, the first community of freed enslaved people west of the Mississippi River. In dusky golden light, Black farmers and white school children inhabit this seemingly utopian middle-America fly over state. I love how Soares’s images break from traditional depictions of segregated, insular, down-trodden communities of color typical of many white Southern photographers throughout history, opting instead for sunny and fierce environmental portraits.

— Erin Jane Nelson