Like so many of those cities who find, by size or offerings or history or all three, the national imagination to become a destination, New Orleans is a city you want to be enveloped by. But like so many cities whose economy is largely dependent on tourism, there is always a gap between how we understand New Orleans –the place as it lives in our national and cultural zeitgeist– and the place and community that it is to those who live there. This was an expanded tension at play this fall, when I visited Prospect.5: Yesterday we said tomorrow, the much-delayed, but satisfying fifth edition of Prospect New Orleans, a citywide triennial. I’m not convinced this isn’t always the case for any large exhibition that takes “place” as a foundational organizing premise, but in the present moment the drift in Prospect.5 feels acute and fascinatingly muddled, a vivid opportunity to negotiate the distance between history and myth across borders and time.

A logistically complex undertaking under “normal” circumstances, the original opening date of Prospect.5 coincided with the onset of coronavirus. Pandemic pushed the opening to fall 2021, and the August 2021 landfall of second most destructive storm in Louisiana history, Hurricane Ida led to a second and late-stage schedule change. Commendably and despite it all, Prospect.5 finally opened over a series of weekends between October 23 and December 11 and will remain on view through January 23, 2022. Spanning fifteen official locations, seventeen satellite venues, and including some fifty-odd artists from across the world, Prospect.5’s epicenter is two massive group exhibitions at the neighboring Ogden Museum of Southern Art and the Contemporary Arts Center.

While Yesterday we said tomorrow is cohesive and curatorially strong, it is best and most absorbable in its micro moments and relational pairings. Standouts at the Ogden include New Orleans artist Willie Birch’s large, quiet drawings of street scenes set alongside Beverly Buchanan’s tiny iconic houses and Tau Lewis delightfully ominous womb-suggestive quilts – a tidy consideration of the intimacy and fragility of home. The Neighborhood Story Project, a local artist collaboration, draws out the voices of generations of New Orleanian women – small altars filled with personal icons and accompanying photographs illustrate histories of a relationship with a spiritual practices. (Also at the Ogden and while not an official Prospect stop, the RaMell Ross’ solo exhibition Spell, Time, Practice, American, Body featuring his acclaimed series on Hale County, Alabama, is phenomenal, and a focused compliment to much of triennial’s thematic labor around place.)

Across the street at the CAC, in one of the strongest curated sections, there are opportunities for confronting the historical weight of “landscape” beyond New Orleans, and the rituals that reveal repressed histories of peoples. Laura Aguilar’s canonical self-portraits, Carlos Villa’s feathered “dream-coats” and Sky Hopinka’s meditative video navigating the route of the Mississippi river (all in the same room) expand the triennial by parsing out the distance between the lived truth (joyful and tragic), and colonial myth that is at the core of our nation’s collective cognitive dissonance.

A mix up of curated and newly commissioned work, some artists clearly used the delayed opening to push the scale and timeliness of their work. The artist Eric-Paul Reige’s giant installation of plush rams (each with eight legs), strung between huge, traditional looms and draped in regalia, woven saddles and bells, rippled with potential energy at that scale -– the sheep, even in their deliberately cartoonish or iconographic rendering, setting the stage for ritual. Celeste Dupuy-Spencer’s monumental history paintings are brutally responsive to the moment – the central painting in the room is a chaotic illustration of January 6. Similarly, Glenn Ligon’s neon signs of the removal dates of various confederate monuments combined Jennie C. Jones’ soaring audio in the Odgen’s library is deeply moving, engaging on the topic without didactics.

I got to see only a fraction of what Prospect.5 has to offer – in part because on my visit the triennial hadn’t fully opened and was still in the midst of staggered openings. But also, because Prospect.5 tentacles its way through the city and across venues, hosting work at traditional sites like the museums and galleries, but also in empty restaurants and events spaces like Rodney McMillian’s videos at the ramshackle Happyland Theater.

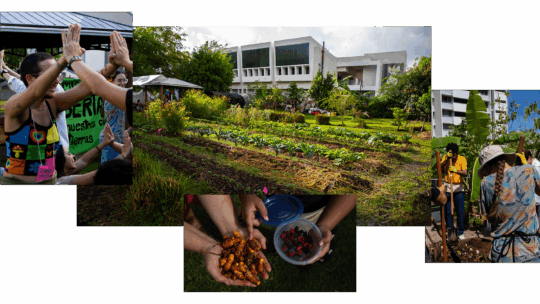

The best use of site united the efforts of the artists with a location or when the artist was particularly adept at considering the complexities of the city beyond the usual hauntings – Carnival, Katrina, Bourbon Street, etc. At the Amistad Research Center, an independent archive housed at Tulane University– for collecting works that “reference the social and cultural importance of America’s ethnic and racial history, the African Diaspora, human relations, and civil rights,” Kameelah Janan Rasheed’s thoughtful “Future Forms” explored the ephemera of Nkombo, a Black literary magazine published in New Orleans in the late 1960s and early 70s. Rasheed engages in the locality of New Orleans by bringing into view a divisive moment in the city’s creative history without too much intervention – the research itself is the work and it is fascinating. Large prints which annotate her exploration of Nkombo are now the tabletops of the Amistad’s reading room, mirroring and magnifying the daily work of the Center’s researchers. Similarly, Paul Stephen Benjamin’s Sanctuary is striking in the garden of the New Orleans African American Museum. Casting out like a beacon, black letters highlighted by purple neon spell “Treme,” Benjamin’s Sanctuary is a sturdy bastion of shimmering black bricks, for one of the city’s oldest neighborhoods and a famous wellspring for Black music and culture, currently undergoing rapid gentrification.

But the work I kept coming back to, which appeared to me in quiet and avoidant moments in the weeks since I visited are New Orleans-based artist Ron Bechet’s trio of wall-sized charcoal drawings at the Newcomb Museum. Not showiest work in Prospect.5, but they are among the most powerful for their quiet exposition of the natural world overlaid by a creeping synthetic order. The largest work, Harriet’s Advice, covers an entire gallery wall with a scene of a log or tree root, tangling with nutrient rot of the forest floor. Defying the initial organic compositional logic, curious vines run straight across and send thin shoots straight up, distinctly unnatural in their precision. The effect of these vines is to lay the image under a rigid and subtle grid.

The title of the exhibition Yesterday we said tomorrow is a short puzzle.[1] It takes a few seconds to figure out where, in time, you are being asked to rest, before locating the show squarely in the present. What Prospect.5 as an overall exhibition might do best by carefully uniting enigmatic New Orleans with a diverse roster of local, national and international artists is acknowledge how profoundly disorienting wrestling with the present can be– to untangle history from myth, experience from expectation in real time. It was standing in front Bechet’s charcoal drawings trying to parse out the connective tissue between the eerie gridded vines and the scene below that I felt this disorientation most acutely, layers at once wholly separate, distinct, and infinitely entwined.

[1] Borrowed and adjusted from new orleans Jazz musician Christian Scott aTunde Adjuah’s 2010 album Yesterday You Said Tomorrow.

Prospect.5: yesterday we said tomorrow is on view across New Orleans through January 23, 2022.