Wandering around Bojana Ginn’s luminous installation at MOCA GA last fall led to my brief and uncalculated obsession with the pixel, arguably the most overlooked tool in contemporary life. The artist’s three large square sculptures, glowing orange and blue through swirled wool, seemed like physical renderings of the grid on the walls around them; the size of the indistinct projected image was so large that the pixels became a visible grid. A set of stacked and overlaid monitors created a wash of subtle undulations across the teal blue screen and mimicked the effect of pressing a finger to a computer screen, briefly interrupting of the grid before the pixels rush back in to right the image. Throughout the room-sized installation, the pixel was pervasive. While the artist’s statement and talk focused on the natural world and light as primary building block, my experience of the work rested firmly in the digital realm and in the breakdown of boundaries between screens and the physical world.

Humor me while I say the thing that everyone must when talking about screens: they are everywhere, from our pockets to our billboards. Our relationships to our screens are more intimate than most friendships; the screen of my iPhone knows what I eat for breakfast, which words I can never spell on the first try (February, Wednesday, birthday—all time-based words), the websites I frequent, and my unproductive hours. We take as a given the presence of the screen in our daily lives—as an hourly necessity—and have the shallowest knowledge of the actual mechanics that operate them, accepting the marvel of the iPhone and computer screens with a Haraway-esque appreciation for sunshine. [1]

But unlike so many of our technological building blocks, the pixel can be measured in units, or in terms of physical space. Pixels are “units of programmable color” on a screen, and the sharpness of an image is determined by the actual size of its pixels. In this way, the pixel is the perfect tool, as demonstrated in Ginn’s installation, for the blurring of boundaries between the flattened visuals of a screen and the corporeal plane.

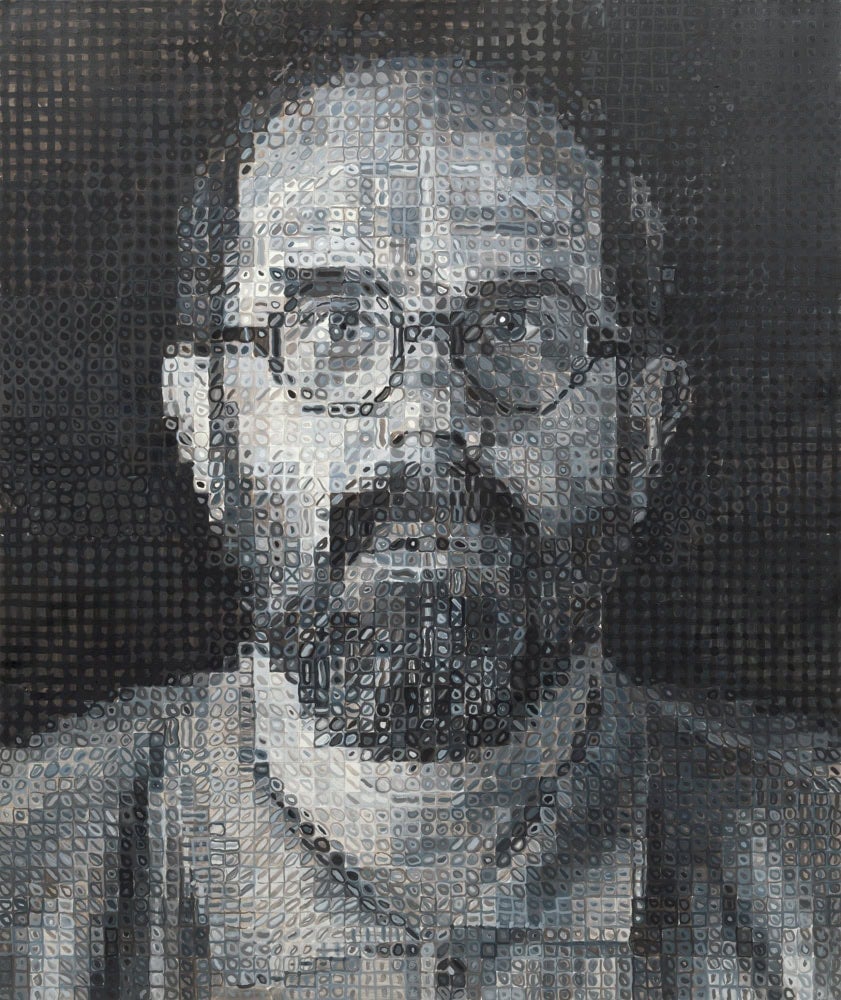

The pixel is not exactly a new visual tool, particularly in painting, having been abundantly used by J.M.W Turner, the Impressionists, and perhaps most famously in Chuck Close’s many pixelated portraits. Up close, each portrait is comprised of color-blocked squares or dots with no discernable pattern. Step backward, visually shrinking the size of the pixels via distance, and the image resolves into Close’s jowly mug. As pixels moved from the painted surface to the computer screen, their prevalence has increased while their visible presence has become more obscure, almost infinitesimally small. But thanks to our reliance on screens, the pixel—which underpins and grids every single image, every open tab on Chrome, every Instagram post, and offers unlimited variations of color and form—is the structural mechanism for contemporary viewing.

In works including Hito Steyrel’s hilarious informational video How Not to Be Seen: Fucking Didactic Educational MOV. File (2013) and Pipilloti Rist’s Pixel Forest (2016), contemporary artists have refused to accept the passive presence of pixels or their use as a mere visual trick. Lesson 4 in Steyerl’s video employs dancing bodies with pixel heads, a resolution chart in the California desert, and dry narration to highlight a simple technological consequence: as image qualities improve, the pixel shrinks and disappears into a seamless picture—not a radical event, but one that hides an underlying structure. Rist’s enormously popular (and endlessly Instagrammed) Forest brought pixels off the screen, creating an immersive, glowing world that viewers could move through, in, and around. In Atlanta, Ginn’s installation magnified these technological tools while simultaneously softening their mechanisms so that they appeared to behave like natural materials. As with Rist’s Forest, a curious softening of the screen pervaded Ginn’s installation, obscuring the boundaries between virtual and lived realities. All three artists—Ginn, Steyerl, and Rist—amplify pixels’ size and mass to encourage the viewer’s confrontation with the oft invisible tool.

If, as critic Rosalind Krauss famously said about twentieth-century modernism, the grid is “the form that is ubiquitous in the art of our century,” the same might be said about the pixel in the twenty-first (and in Ginn’s installation in particular). [2] The pixel is a contemporary version of the modernist grid, the structural support underlying our reliance on screens, phones, and computers, both in artmaking and in daily life. But unlike the endless grids of the mid-twentieth century, which reduced painting to formal concerns, pulling the structure of the pixel off the screen opens myriad opportunities for the reorganization of visuals and, as a conduit between the embodied world and the flattened digital one, a useful technique for evaluating our staggering dependence on screens.

[1] “Our best machines are made of sunshine; they are all light and clean because they are nothing but signals, electromagnetic waves, a section of a spectrum, and these machines are eminently portable, mobile – a matter of immense human pain in Detroit and Singapore. People are nowhere near so fluid, being both material and opaque. Cyborgs are ether, quintessence.” —Donna Haraway, “A Manifesto for Cyborgs: Science, Technology, and Socialist Feminism in the 1980s” in Socialist Review, Vol. 15, Issue 2, 1985, (65-107).

[2] Rosalind Krauss, “Grids” in October, Vol. 9. Summer 1979, (50).