Jean Genet’s 1943 novel Our Lady of the Flowers is an extended, fantastic ode to masturbation and queer desire. Narrated by the author, who wrote it while in prison for committing burglary, the darkly sexual, lyrical work is framed as a means for amusement, arousal, and escape from the isolated, alienating experience of being incarcerated. Accounts of violent men, drag queens, and sexual outlaws are joyous and eroticized, inverting values that are often understood as fixed (or even enforced by society and the state), especially at the time when the book was written.

Lonely, separatist, and sometimes hermetic existence is central to the identity of a number of queer archetypes found in western literature and art. Cowboys, sailors, soldiers, and the imprisoned are all more or less made separate from society at large, sometimes by choice and sometimes not. Historically this distance has afforded these people broader access to divergent sexual practices. In prison, at sea, on the frontier, or at war, male same-sex desire was and is tolerated and sometimes encouraged as a distraction, or as the fulfillment of a need that would otherwise be irreconcilable.

A copy of Genet’s Our Lady of the Flowers is displayed prominently on a mantle in the home of Kentucky artist Mike Goodlett. It’s one of just a few objects in his sparsely decorated home in Jessamine County, which stands at the end of a mile-long gravel driveway lined on both sides by low hanging trees. In addition to his own artwork (largely works on paper in graphite and spray-paint and sculptures made of plaster and cement), a bed, a few chairs, bananas, and coffee are all that occupy the rooms of the two-story white farmhouse. Remnants of midcentury wallpaper and floral-print linoleum flooring adorn a few of the rooms, which have otherwise been painted white and somewhat yellowed by age.

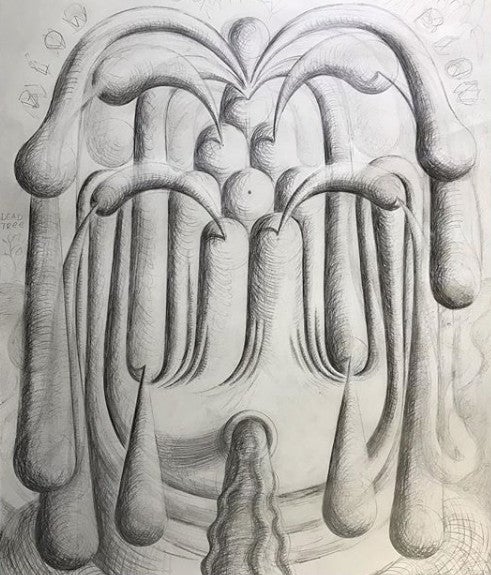

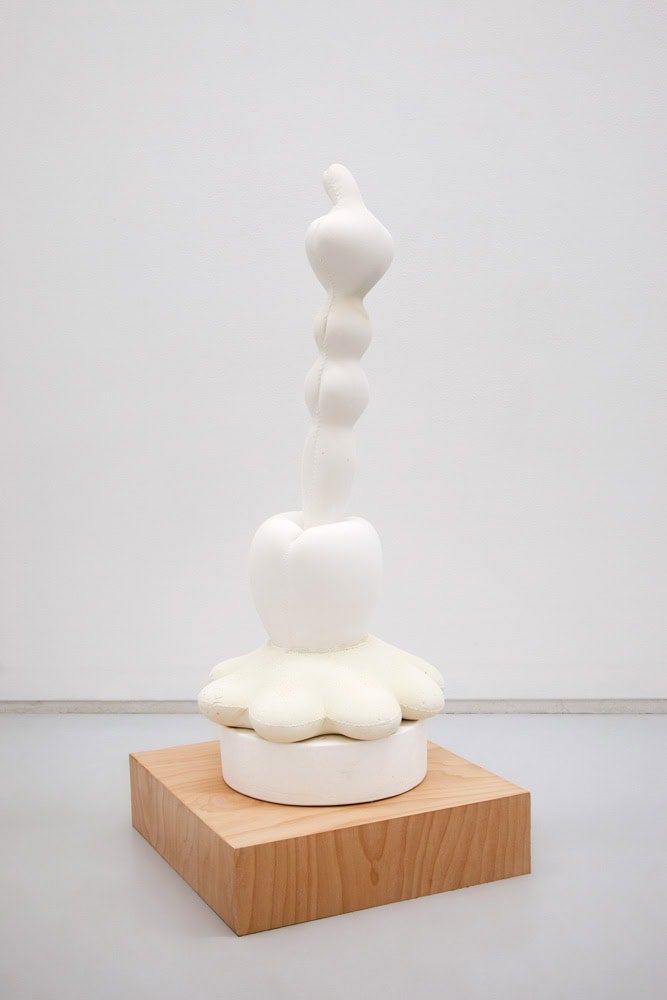

As it is made from the perspective of a person who isolated by geography and his sexuality, Goodlett’s work resembles Genet’s in that it attempts to supersede his lived experience, positioning isolation and loneliness as doorways into lavish, highly personalized desire. Particularly in his sculptures, Goodlett reduces physical desire to its constituent parts before reassembling those throbbing, bulbous, and oozing pieces into a monstrous and alluring whole. Made up of undulating curves, holes, and appendages, his objects and drawings are simultaneously passive and dominant, active and receptive. A few body parts are recognizable: a foot in a black nylon stocking, fingers, faceless subjects, and oversexed bodies are self-contained and sealed off from other forms and figures, existing exclusively for self-pleasure.

Goodlett has recently begun to consider his sculptures as altar-like objects. Their holes house spirits. They memorialize ways of desiring queerly which sometimes feel, for better or worse, in danger of dying out. During my visit, Mike and I discussed a time in Lexington, Kentucky—the closest urban center to his home—when cruising for sex in the YMCA locker room, the Greyhound bus stations, or the gay bars downtown was the norm. It was dangerous and thrilling and sometimes fruitless.

There are many benefits to broader acceptance of queer experiences and sexuality in the media and elsewhere, as many queer people see themselves increasingly reflected in the world around them. This version of relatively mainstream acceptance, however, is often only available to certain members of the queer community and is distributed unequally across lines of race, class, and gender. As queer people contemplate our roles in a social order that has begun to provisionally accept us on its own terms, it becomes increasingly urgent to investigate what we learned while living—and sometimes thriving—alone, in the dark: in the park at twilight, in the locker room, or in Goodlett’s case, in a farm house in Kentucky, taking an amalgam of intangible, imagined, fragmented desires and making them concrete.

Sculptures by Mike Goodlett are on view in the group exhibition Doldrums at Mrs. Gallery in New York through August 2. Mike Goodlett: Almost Folly is on view at Tops Gallery at Madison Avenue Park in Memphis through August 18.