In this letter, Queens, NY-based writer and curator Robert Grand responds to Sara Estes’s review of Nashville painter Jodi Hays’s recent exhibition “God Sees Through Houses,” originally published on BA on November 6, 2018.

Letters to the editor are welcome at any time and may be published at the editor’s discretion.

Sara Estes argues against subtlety of intentions and political persuasions in her review of Jodi Hays’s exhibition “God Sees Through Houses” (Lipscomb University, closed October 18). The writer latches onto Hays’s claim that the exhibition contends with the Department of Homeland Security’s “Zero Tolerance” policy of splitting up families at the U.S.-Mexico border. In particular, Estes grapples with Hays’s statement that painting could offer “an alternative form of measurement, one in which the power of sight…could be used to advocate…”

The last few paragraphs of Estes’s review taps into a larger conversation happening across the country. The author has narrowed her focus onto abstract painting, but really, every creative is asking themselves the same questions. In the face of environmental destruction, countless human rights violations, and a deeply divided public, what is the point of making art? Wouldn’t our time be better spent collectively organizing, canvassing in swing districts, or donating to the endless string of nonprofits that work tirelessly to right the wrongs of a corrupt and unjust administration? If we continue to make, shouldn’t we focus on producing calls to action? If we did, would they even be effective? Artists also have to contend with the market—how does one continue to produce knowing that financial support primarily comes from the wealthy, from collectors whom directly benefit from the exploitative financial policies which have been in place for decades?

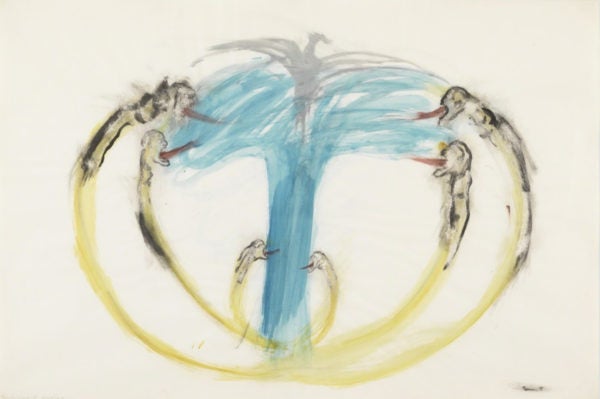

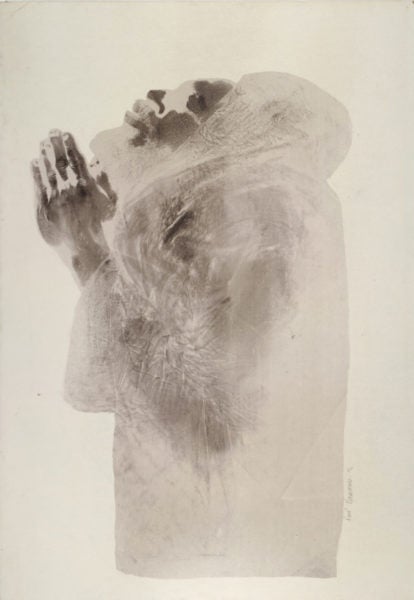

Art making at its core is a form of problem-solving; in “God Sees Through Houses,” Hays is trying to answer the question of why art now for herself, in the face of not only political but personal turmoil. Much like “Keeper,” the artist’s 2017 solo show at Nashville’s Red Arrow Gallery, “God Sees Through Houses” finds Hays reexamining her decades-long painting practice as a whole. It’s as if, in these exhibitions, Hays admits that she can no longer indiscriminately pull architecture, symbols, and figures from the wider world. She must wrestle with their original context and the charged associations that can accompany them. In my eyes, this marks a breakthrough for the artist.

I believe the abstraction is a benefit. A work like Entry could reference multiple real-world acts, events, and conclusions. We’re given just enough information to be unsettled—to reflect on headlines we’ve read, tweets we’ve scrolled past, Facebook videos we’ve paused before their grim conclusion. All these instances speak to the precarious position of humans under surveillance, wherein people are rendered as anonymous blurs from equipment lacking enough pixels to tell the full story.

In Estes’s eyes, Hays has failed at transmitting all this to the audience; that’s fine. But instead of stopping there, Estes goes further—seemingly writing off the entire practice of abstraction in the current day. Her argument goes from micro to macro as she muses, “I cannot help but wonder if it’s possible for abstract painting…to address such specific, urgent political subject matter.”

I can’t say I fully disagree with her, but the statement is too generalized to hold much merit. Additionally, I have trouble with this criticism being directed towards Hays and the array of works in “God Sees Through Houses.” Nashville is populated with painters invested in abstraction, and yet these concerns are never brought up in consideration of their works or exhibitions. Frankly, many of their practices could benefit from this needling, from a demand to contend with the world writ large. I’d rather have an artist like Hays—one who, in Estes eyes, may fumble in her quest to merge the abstract with the political—than an artist like David Onri Anderson, whose dry depictions of apple cores and Chinese lanterns evade explicit political engagement.

I greatly appreciate Estes bringing such important, and urgent, discourse to the forefront. There’s a more nuanced argument to be had here, one that I hope Estes continues to develop and one that I will consider. As for now—I simply wish her criticism had cast a wider net.