Located in what is now known as Cherokee, North Carolina, on the Qualla Boundary, the sovereign land of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (EBCI) and ancestral homelands of all Cherokees, The Museum of the Cherokee People is one of the longest-operating tribal museums in the country. Established in 1948 to preserve and perpetuate the history, culture, and stories of the Cherokee people, the museum has undergone significant transformations in recent years. Disruption, a 2022 project, invited enrolled artists to respond to the recent removal of funerary and culturally sensitive objects from public view, contributing new, and sometimes site-specific, works in the process. Last fall, the institution changed its name to reflect an Indigenous-first narrative and renewed commitment to community: ᏣᎳᎩ ᎢᏗᏴᏫᏯᎯ ᎢᎦᏤᎵ ᎤᏪᏘ ᎠᏍᏆᏂᎪᏙᏗ (Tsalagi idiyvwiyahi igatseli uweti asquanigododi), Museum of the Cherokee People. In Cherokee, the new name approximately translates to: “All of us are Cherokee people. It is all of ours, where the old things are stored.” The museum also announced plans to construct a large offsite collections facility and a multi-year renovation and reinterpretation of their permanent exhibition, last updated in 1998, incorporating community input, interdisciplinary perspectives, and scholarship from new generations of Cherokee historians and Indigenous professionals.

sov•er•eign•ty: Expressions in Sovereignty of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, on view through February 28, 2025, is a preview of these larger efforts. The show presents a small grouping of objects and artworks from the museum’s collection to educate visitors about the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians’ autonomy, its relationship with the United States federal government, and how the tribe has defined its own relationship with its land, people, and culture.

Below, Burnaway’s Carolinas Editor-at-Large Robert Alan Grand spoke with exhibition organizers and museum staff members Dakota Brown (Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians) and Evan Mathis to hear more about the exhibition and wider shift for the museum. (The Qualla Boundary was not heavily affected by Hurricane Helene, and the museum is open regular hours.) The following conversation has been edited and condensed.

Dakota Brown (Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians) and Evan Mathis. Photos courtesy of the Museum of the Cherokee People.

ROBERT ALAN GRAND: Can you talk about the impetus for this exhibition, along with the museum’s new direction and significant overhaul?

DAKOTA BROWN (EASTERN BAND OF CHEROKEE INDIANS), DIRECTOR OF EDUCATION: The exhibition is based off of something that we heard commonly in the community, that there seems to be—within our own community and visitors—a misunderstanding of who Native people are and what tribal sovereignty looks like, and what it is. That’s why we thought about making this exhibition focused on the theme of sovereignty. It reflects our new methodologies and ways of thinking about our exhibits—we’re moving away from a timeline model and toward a theme-based model. It also goes along with another focus of our museum: being a first voice museum and making sure that we are telling Cherokee stories from our perspective.

RAG: Artists and artworks play a pivotal role in this new grand narrative. Can you talk about some of the artists featured and the works chosen?

EVAN MATHIS, DIRECTOR OF COLLECTIONS & EXHIBITIONS: These were all objects from our existing collection. When I think about sovereignty, the piece that sticks out to me is the large soapstone sculpture by Lloyd Carl Owle (EBCI). He just passed away in December 2023—he hasn’t been gone quite a year yet—but the piece he carved is called Life of Tsali (date unknown; accessioned into the museum’s collection in 2004.) The reason we selected that piece was because Tsali is a figure in our Cherokee history that did contribute, in ways, to sovereignty; however, his story has been mythologized and twisted, almost. And in the Museum’s former main exhibit, which closed in 2023, the only object we had to discuss Tsali was the gun that killed him. Now, we have this massive soapstone sculpture that celebrates what his and his family’s life may have looked like.

DB: That piece just shows, if you know about the Tsali story, what a complex and hard time the period of Removal was. That piece of art exemplifies just how complicated and difficult that time was, the types of decisions each individual had to make just to survive.

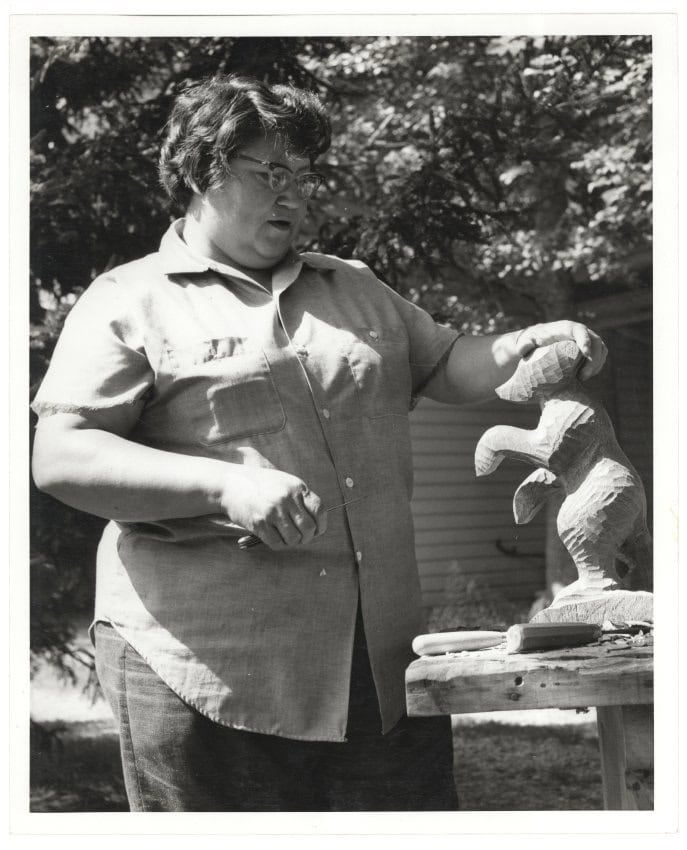

Amanda Crowe (EBCI) is one of our very well-recognized artists. She had the opportunity to study art in a way during that time that most other Cherokee folks did not have access to, which is amazing.

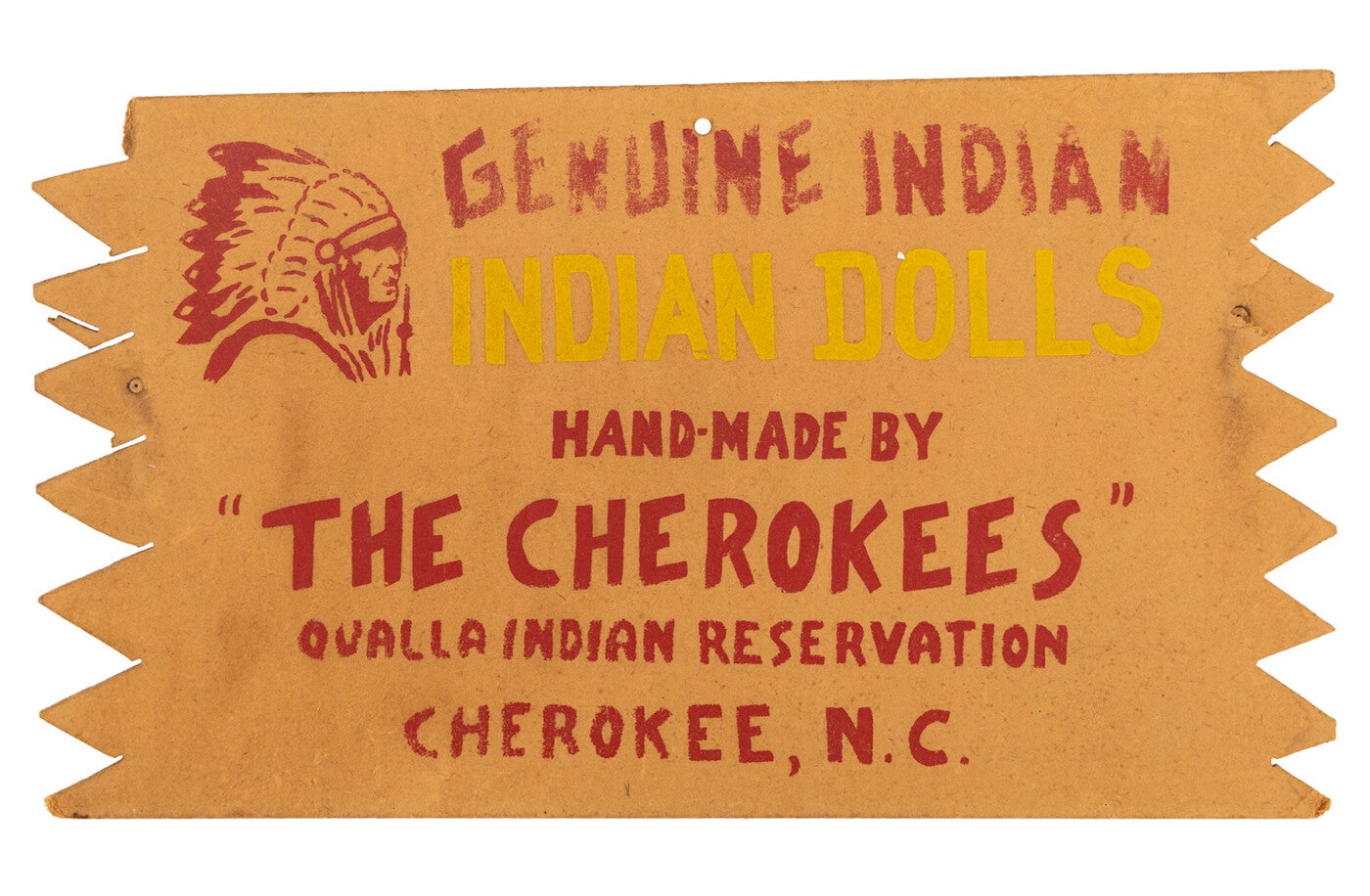

I think one of the most beautiful things about Amanda is the way she could have done a lot of things away from her community: she could have had this amazing career—she did have this amazing career away from this community—but when we talk about what it means to be a part of an Indigenous community, I think her story really exemplifies that. We all feel this today, this responsibility to come back and serve our community in some way. Although Amanda didn’t have any children, she left a beautiful legacy of carvers in our community. Also, I think, she was a part of this time period where we, as a community, were really leaning into different stereotypes that served our community for a long time and created a tourist industry. That was important for me to highlight and talk about.

MotCP Executive Director Shana Bushyhead Condill (EBCI) had started talking about the idea of strategic essentialism and using stereotypes and misconceptions about your community and minorities or underrepresented individuals—using those to create innovation, to create economies, using those things to build up our community in a way is something that we absolutely did.

Something I love about Amanda’s piece is that it’s reminiscent of that time that we were using those stereotypes and things like that to build a tourist economy, but the beautiful thing that comes from this time period is that it uplifted and made an industry for artists to make Cherokee art. It really transformed the way that we see Cherokee art—that time period of monetizing and making something that’s sellable to the public, whether it’s baskets, carvings, fingerweavings. The art shifted at that time from being something that we did for utilitarian uses in a utilitarian way and it truly becomes art. Amanda really represents, or is one of those folks that is a part of that time period, that transition of our traditional cultural practices transitioning into this true art form that is really valuable to our community.

EM: I’ll add that, as Dakota mentioned, people consider her an ancestor. One of our respected contemporary artists is John Henry Gloyne (EBCI), an amazing EBCI tattoo artist, painter, wood sculptor—everything else you can think of. I think it was him that I first heard call Amanda his “woodcarving ancestor.” He talked about how he learned from Bud Smith (EBCI) at Cherokee Central Schools, and Bud Smith learned directly from Amanda Crowe. The vast majority of woodcarvers here can directly trace their lineage back to Amanda. The fact that she didn’t have kids doesn’t mean she’s not an ancestor and doesn’t mean that she doesn’t have this major lasting legacy in the community today. There’s something really beautiful about that, and it’s something to strive for: to leave a lasting, positive impact on your community.

DB: The way we view family is different in Native communities and here in Cherokee. You don’t have to be directly related to somebody in the typical sense you’d think to have this strong connection to family, to community. She’s a perfect example of that, though she has a ton of biological family in the community, she has an even bigger extended carving family.

RAG: It’s refreshing to see sov•er•eign•ty organized by concept and not chronologically. Why did you decide to go that route?

DB: sov•er•eign•ty is us dipping our toes into this new approach, and we’re getting some great information and feedback to carry forward into future exhibitions.

EM: For example, Dakota and I met earlier this week and were planning for our new main galleries and looking at feedback from the community committees we hosted. We were trying to pick main topics that these sub-points could fit into, and we were really struggling because you could make any of these sub-themes fit within any of these major topics we’ve started with. When you interpret Indigenous history, you don’t focus on a timeline: everything is so connected in Indigenous communities and worldviews are interconnected. It’s really hard for us to separate out and do things on a strictly linear timeline. In our minds, we’re constantly thinking about the previous seven generations and the seven generations that come after us and where we fit in the middle.

DB: Our Indigenous worldview doesn’t work in a linear timeline; it’s cyclical, and it loops over time. So, the way that we view time as Indigenous people doesn’t work in this clean, linear fashion, and as I study and research history, I find that history is very complex because humans are very complex. This clean, linear timeline doesn’t really fit with the complexities of what history and the complicated story of human existence really is. I think that this is one of the main reasons a timeline model doesn’t make sense for us anymore.

On a practical level, a timeline model creates limitations for us; the way we tell our stories, because everything is so interconnected, a timeline model forces us into a particular time period, and it also makes it really hard for us to change and be topical in the moment. When we’re looking at how we approach our exhibits, if our timeline ends and we see this—and we see this with the Museum’s former main exhibit, where our timeline ended in the early twentieth century—it was really hard to talk about topics today, and made it hard to pivot and bring that narrative forward, which we know is a huge issue in the way the world sees Native people. They always see us in the past. Having a timeline creates issues for how we can address that misconception.

EM: As an example: even when you think about things like Removal and the Trail of Tears, I have really close friends in Oklahoma today. We all have our own craft nights, and when they visit me here, they come to my craft night; when I’m out there, I go to theirs. One of my friends said, “I really want to go to Green Corn [on the Qualla Boundary], but I can’t afford to travel that far.” We know the Removal affects us today, but it had never hit me that hard: that if we want to go to Green Corn at different ceremonial grounds, we should be able to pop in a car and go with friends, but we can’t, because they are fourteen hours away. I’m not a tribal member, I’m a community member, but we all feel it today; it has lasting effects.

DB: It’s created this lasting separation that’s still felt today: we still have a connection to all these people in Oklahoma, but Removal disrupted that kinship system, and it’s still happening today.

EM: We’re still in community with them, but we can’t physically be, because of the distance.

RAG: Another fundamental section of the exhibition examines the role of tourism in spurring economic development and contributing to the myth that the Qualla Boundary is “a reservation” instead of land owned by the Cherokee people outright.

DB: Representing the Qualla Boundary as a reservation was a tactic during a time that we really needed the tourism. At the time when tourism was seen as an opportunity to build an economy, we were considered one of the poorest communities in the country. We went through a lot at that point as a people. After the Removal period, the Cherokee people who were still here were left to pick up the pieces and try to become our own separate Cherokee nation, and that was a journey. We had to buy back our land base, and there were a lot of hardships. We went through a lot, and we were really struggling financially. So, tourism created this opportunity and we were able to, for the first time in a long time, really care for our families. People were able to put food on the table. There was industry and jobs here for the first time in a really long time. Tourism has done great things, it has been great for this community; and yes, there were a lot of things we leaned into building that tourist identity.

The Museum comes out of that directly; it’s tied to that time period where we were building a tourist economy and it was seen as a tourist attraction in our community. I think we’re lucky that we had the leadership that we did who saw the vision for a tourist economy and made the decision to build it. Ultimately, our museum wouldn’t be here if it wasn’t for that; it’s the reason our museum exists.

But I also do think that we, as Cherokee people, have always changed and evolved over time, so we’re kind of in a moment of evolution for our community and for what our tourism is going to look like. I think that all of that was very intentional, and that goes back to making sure we include the idea of strategic essentialism into the sov•er•eign•ty exhibit. Making these intentional decisions is absolutely an expression of sovereignty, and it’s positively and negatively affected our community. It perpetuated Cherokee art.

I also think that economic stability and not living in a place of scarcity brings about healing and opportunities that we as a community didn’t have—my dad’s generation and my grandparents’ generation didn’t have the opportunities that I have today. I think about that a lot, and I think that’s an important piece to this. We are building on the legacy of what tourism has brought to our community, and I think that we can transform it and make it work for the next seven generations that come after us.

It will continue to evolve and be an economic driver for our community. I think we’re just in this pivotal time, a moment of change, that we can reevaluate and rethink what we want it to look like and how we want it to work for us as a community and not just our visitors. Everything has been so focused on our visitors, and now we’ve gained some economic stability in our community, so I think we can help contribute to that economy, but it will take some shifting in the way we think about tourism here.

One adverse effect of the tourism economy is that we as a people are impacted by the way that outsiders see us. I do think some tourists who come here have a hard time not viewing us in a particular way. And I know that with sov•er•eign•ty and even the exhibition Disruption before that, it was hard for some of our visitors to comprehend how we can be a modern, living people. There is the idea that we’re only supposed to exist in a particular past that really has to do a lot with the stereotypes of how Native people are viewed in the United States. There are a lot of misunderstandings that Americans and visitors who come through here bring with them. Sometimes, it can be really hard to break through those; sometimes, they are the only conversations we get to have. It becomes really difficult to have a deeper conversation on things that are affecting us today, true things about our history and ideology, and we can never get on this deeper level because we’re always having to start from this base level of understanding.

“The fact that we are on Cherokee land right now that’s still in the Eastern Band’s possession, that the EBCI still owns this land…that’s important.”

I think that a lot of that comes from misconceptions and stereotypes that most Americans and other visitors have about Native people; there’s still this broad gap in understanding that Native people are incredibly diverse. That can be a huge hurdle we have to overcome through interpretation and the way we approach exhibits. We have to lay some groundwork to develop a deeper level of understanding of topics that are meaningful to us and our community.

EM: I’ll add that the Qualla Boundary is not a reservation, but also it legally holds the same weight as a reservation. The Qualla Boundary is different than most “Indian reservations” because the land was purchased back directly by enrolled members of the EBCI. However, the land is held in trust of the federal government, so it has the same protections as other Tribal Nations have reservations.

DB: I do think that it was a tactic, and I understand that, at the time, it was the appropriate choice to make, to label this as a reservation. It was a tactic to build our economy and it worked; it was smart and innovative. But I think we’re at a place now that—here in the community, we know this isn’t technically a reservation—it makes me want to highlight that story, because I don’t think that story’s been fully told or understood, about why this is a boundary. As a historian, that history is important to me. I want to know the smart, tactful, and strategic ways that Cherokee people went about purchasing back land here in a time that was really difficult; how they pulled money together and were inventive about loopholes to own land here. That story is so interesting, and I want to tell it. I don’t think we’ve been in a place before to tell that story, because we needed to lean on the idea that this is a reservation to build that tourist economy, but now that it’s built and thriving, we can kind of circle back and tell some of those untold stories in our history.

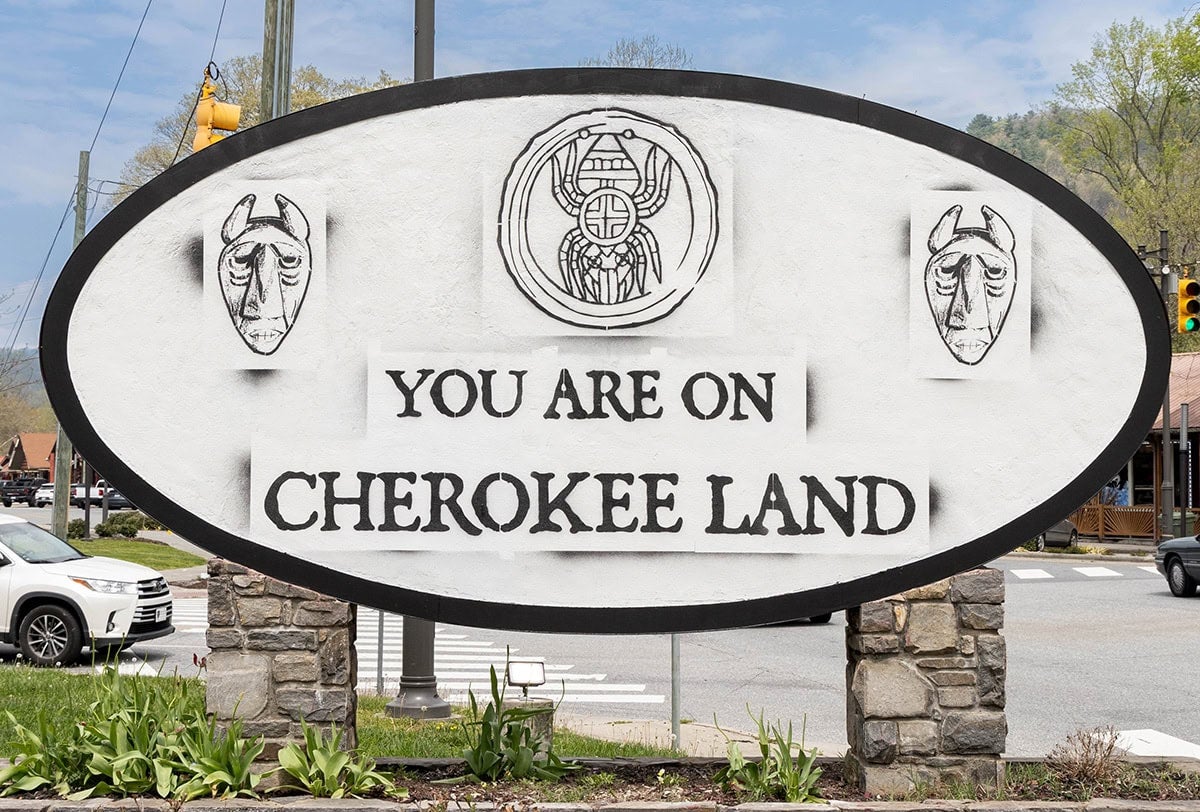

RAG: I also want to touch on the revamp of the museum’s street-facing sign, an artistic intervention by Luke Swimmer (Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians). Days after the commission was revealed, the Tribal Business Committee forced the museum to remove the sign.[1] Now, it’s on view in your lobby–can you talk about that process?

DB: It was never meant to be our permanent sign forever—we really viewed it as this artist intervention, and we did try to make sure that we gave Luke artistic freedom with what he wanted to do and how he wanted the sign to look. What prompted it was that we changed our name and the sign was no longer accurate: it represented our old name, Museum of the Cherokee Indian, and we changed our name to Museum of the Cherokee People.

I think [Executive Director] Shana [Bushyhead Condill (EBCI)] in particular had the thought behind it; at the Field Museum, when they started their Native Truths exhibition, one thing they did was overlay the cases, and so she was inspired by that and saw an awesome moment to take our old sign and do this artist intervention: have an artist come up with an idea of how they want to change the sign. The only parameters were that it had to have “Museum of the Cherokee People” on it, and he ran with that. It was meant to look like graffiti, like someone came and tagged the sign; Shana was also inspired by some of the writings and graffiti from the Occupation of Alcatraz, which was very much a part of the American Indian Movement.

I think Luke really ran with it and made it look like tagged and spray painted. We knew at some point the sign was going to moved into our collections—as soon as he touched it with paint, we considered it a piece of art. As soon as it was going to be taken down, it was going into our collections—that was always the plan for it. When we found out that we had to take the sign down, it was a no-brainer. Business Committee gave us the option to “fix” the sign and restore it back to what it was, but for us, the sign was a piece of art; to return it back to its original form would be disrupting or damaging Luke’s art. We knew that we had to take it down, and we were okay with that.

Because it was accessioned as an object in our collections and we didn’t originally plan on displaying it in our lobby—we thought it would be up outside much longer!—but because it was up for such a short amount of time, we wanted to create access to the sign for Luke, for his family, for our community, and that’s why we chose to put it in the lobby.

One of the things I love about everything that happened is that Luke intended for this to create conversation and dialogue in the community, and that’s exactly what it did, and the controversy with taking it down created even more dialogue and conversation within the community. I just love how art can be a catalyst for conversation and dialogue. I think this is definitely an example of that in our community. And because it was art, not everybody loved it; there were a ton of people who absolutely loved it and thought it was wonderful, and some people who didn’t understand why it was spray painted. Regardless of what you thought about it, it was meant to be this conversation; it was meant to create conversation in our community, and I think it did that. I really love this piece; it made it almost an activism piece, because the kind of conversation that was started in our community. That part of it, I really love. I think that it served its purpose.

EM: One side of the sign Luke changed to say, “You are on Cherokee Land,” and for some reason that was considered by some to be “unwelcoming” to non-Native visitors. One of my favorite comments we received is “Isn’t that the whole point? Isn’t that why people come here: because it’s Cherokee land, and it’s not the same as everywhere else?” We know Cherokee land goes beyond where we are—the Qualla Boundary is on 0.00067661% of the original Cherokee territory—but for us to have that teeny-tiny, minuscule amount, and have a sign that said it was considered unwelcoming, is humorous to me.

DB: I think that’s the important part of why it’s related to sov•er•eign•ty—the fact that we are on our own land, that there was a lot of history that happened and a lot of decisions that had to be made very tactfully, and strategic thinking of how we could maintain a homeland during this time of removal when all of our land was being stripped from us. The fact that we have a home base here is significant and important, and it took some really, really smart people, our ancestors who did some amazing strategic thinking, so we could still be here. We had to purchase back every piece of land that was taken from us to create the Qualla Boundary. The fact that we are on Cherokee land right now that’s still in the Eastern Band’s possession, that the EBCI still owns this land…that’s important.

I do think that, hopefully, there are always different perspectives to gain, but we’ve had one perspective in our community for a really long time. We’ve had one idea of what tourism has to look like, because the economy here still heavily relies on tourism in some form or fashion. I think we’ve been trained from a particular time period that tourism has to look one way, but I think we’re learning that tourism can look many different ways, and a tourist economy can be a diverse economy and doesn’t have to rely on one perspective or way of thinking.

EM: For the name change, [Executive Director] Shana [Bushyhead Condill (EBCI)] worked with fluent Cherokee speakers to help us translate the Museum name into the Cherokee language, and there is no word for “Indian” in the Cherokee language. The literal translation is “principal people,” or “the people.” That was a significant change for us; it sparks dialogue through the community of when it’s appropriate to use the term “Indian.”

We only use the term “Indian” at the Museum when using legal terms, and so even with the name of the tribe, the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians—that’s a name that was, from my understanding, imposed by the federal government. “Indian” is a legal term in federal Indian law. We’re very strategic about when we use that term, because as we all know, Indians are from India and not indigenous to the US.

DB: But also, these homogenized terms like “Indian” or “Native” or “Indigenous,” “Native American”—all those terms don’t represent all of us as individuals. Depending on who you ask, you’re going to get a different answer of whether that’s offensive to them or not. For us at the Museum here, we want to be a museum for all Cherokee people, and so that was one of the motives for us to change the name—there were some younger Cherokee people working here, and we’d have visitors come in, and they’d ask them not to call them Indians because they were uncomfortable with it. But, because we had it on our sign, in the name of our museum, our visitors challenged our staff on how they wanted to be identified. It was creating this tension. On a daily basis, this was a topic of conversation we had to confront. So, the name change was a way to protect our staff and also try to be welcoming of all Cherokee people.

When Shana started working with speaker Maria Junaluska (EBCI) on the translation and having the name come from a Cherokee place, the word Marie used to describe us was “Cherokee people.” It aligned with our language, it aligned with the way she referred to us, and that’s the other part of why this name makes sense, and why this made sense to change.

EM: I think it was [MotCP Designer] Tyra [Maney (EBCI, Diné)] who I heard say, “if not everybody identifies as ‘Indian,’ why would we continue to perpetuate that?’”

DB: And some still do, and that’s their right to. All of these terms are made-up terms that non-Native people placed onto us. Ultimately, what we always want to be called is our nation. It doesn’t really matter what term an individual Native person chooses to represent themselves.

[1] Scott Mckie B.P., “Museum of the Cherokee People Made to Remove Sign,” The Cherokee One Feather, June 3, 2024, https://theonefeather.com/2024/05/31/museum-of-the-cherokee-people-made-to-remove-sign/.