On a short, leisurely walk we recently took together, Atlanta-based artist Iman Person led me along the proposed path for Waterlust, her upcoming installation for Flux Projects’ latest iteration, FLUX: Grant Park. The weekend-long, park-wide exhibition shows a new approach to the organization’s public art events, such as the widely-panned, most recent FLUX Night in 2015. Waterlust is one of four artist projects in FLUX: Grant Park (September 27-September 30) that aim to “give voice to the historic greenspace.” Rachel Garceau’s tenderly crafted porcelain stones directs viewers in a winding path through the park in her installation Passage. The Toolbox, a series of temporary installations and performances by Rebecca M. K. Makus and her collaborators Elly Jessop Nattinger and Peter A. Torpey, responds to different sites throughout the park. Artist and choreographer Lauri Stallings’s project Land Trees and Women presents a series of live performances, conversations, and movement workshops over the weekend. Like Person’s Waterlust, each project will examine Grant Park and provide new avenues for visitors to explore the Atlanta fixture.

As she described her plans for the site-specific, low-impact sculpture—which also incorporates sound elements—we talked chiefly about water in all its multiplicities: as both ephemeral and constant in its many different forms, and as an element that acts as a vessel and yet requires containment. In Waterlust, by circumstance and design, the central source material is present only by implication. While we walked, Person described her personal relationship to the resource. For her, water is not a casual utility; she treats her consumption and use of it with careful, critical attention. She reveres water for its qualities as a tool in ritual practice, through which she believes it is capable of embodying memory and affecting dreams. More broadly, Person’s artistic practice is frequently engaged with considerations of how ritual and embodied performance might invoke and relate to nature without invading or replacing it, as the artificial and built environment so frequently does. Person says Waterlust is, in part, a call for Atlanta to respect its hidden streams and larger rivers as rapid development in the city continues.

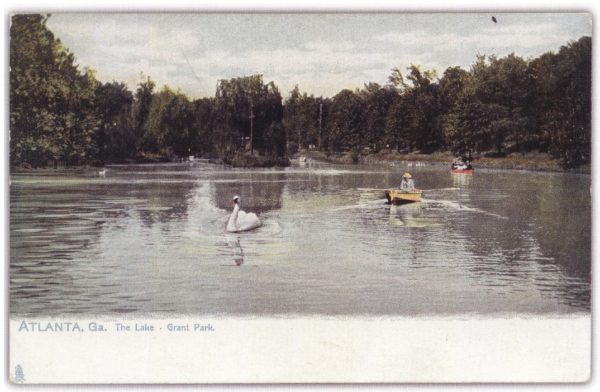

In surveying the history of Atlanta’s oldest public greenspace, Person discovered Grant Park originally housed five springs and water sources, including a lake. Founded in the late nineteenth century after railroad engineer Lemuel Grant donated one hundred acres to the city, Grant Park was originally the center of the suburban, Victorian neighborhood that shares its name. For the next half century, Atlantans enjoyed the park and its defining feature, the six-acre Lake Abana, which hosted spirited boating and swimming. In the 1960s, in a bid to maintain racial segregation, the lake was drained and paved to make way for the zoo. Various renovations gradually eliminated all remaining water sources in the park except Salaam Spring, the source of the pond located just north of Zoo Atlanta.

The only evidence the locations of these streams are rainstorm drainage ditches and washes. During the frequent summer rains, Person described how the streams are temporarily resurrected. Similarly, in Waterlust, those lost currents are physically invoked again by Person, if only for a weekend. Sending streams of iridescent fabric flowing through the trees and alongside the concrete pathways, Person produces a subtle memorial to Grant Park’s water by retracing former routes. Along the installation’s path, visitors will stop at three totems or “Sound Channels,” which Person developed in collaboration with musician Jeremi Johnson (who also performs under the name 10th Letter), each playing audio of the sounds of water and recordings narrating the history of the park. Visitors will follow the visually flowing installation from a spot near the entrance to the Grant Park Pool, moving along the path toward Salaam Spring and the zoo. Waterlust suggests the ephemeral, ritual aspects of water as well as the fact of its material necessity, drawing forth the lost springs to urge public consideration of the effects of segregation and development on our most vital natural resources.

The project has its roots in site-specific land intervention, but Person is practicing a decidedly different method from the artists we historically associate with Land Art. The mostly white, male, conventionally canonized artists of Land Art spent the bulk of their energy bringing unnatural forms into natural settings, competing for size and grandeur with lakes and deserts and enacting an exaggerated violence on the landscape in the form of slices, cuts and big ass holes. If, historically, this version of Land Art has aggressively asserted the artist’s presence in the landscape, Person’s site-specific installation does the opposite by returning natural form to the built environment of the park. More akin to Jean-Claude and Christo’s billowing installation The Gates, which gave visible physicality to wind currents in Central Park, Person’s Waterlust, rendered in shimmering fabric, returns the presence of Grant Park’s eradicated water.

While simple in its premise, Iman Person’s Waterlust will likely operate as powerful conduit for examining Atlanta’s future relationship with water. After a year of increasingly scary news about burning counties and flooded cities; with Flint, MI, still without safe drinking water; and as countdown clocks tick toward Day Zero water in Cape Town; in Waterlust, Person bares out a locally specific, visual response to the growing anxiety about water that is reaching a crisis point globally. As is the case with other endeavors—artistic and otherwise—advancing conversations about consumption of our natural resources, Waterlust feels current, quietly urgent, and long overdue.