While consumers and economies across the world have become increasingly connected through globalism, divisions, hierarchies, and other inequalities continue to plague current systems. As was noted by the late photographer Diego Camposeco in an essay for this magazine last year, discussions of these dynamics today tend “to use the language of the ‘Global South,’ a term that originated in writer and activist Carl Oglesby’s 1969 description of American ‘dominance of the global south’ in relation to the Vietnam War.” The dichotomy of Global North and Global South continues to describe a power relationship where the former dominates the latter. Today these distinctions most commonly refer to the economic definition set by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), wherein the North is recognized for its high national income and the South for its middle to low income. Culturally and politically, the Global North and South have been grouped by shared histories of colonialism in which, again, the Northern countries have been dominant.

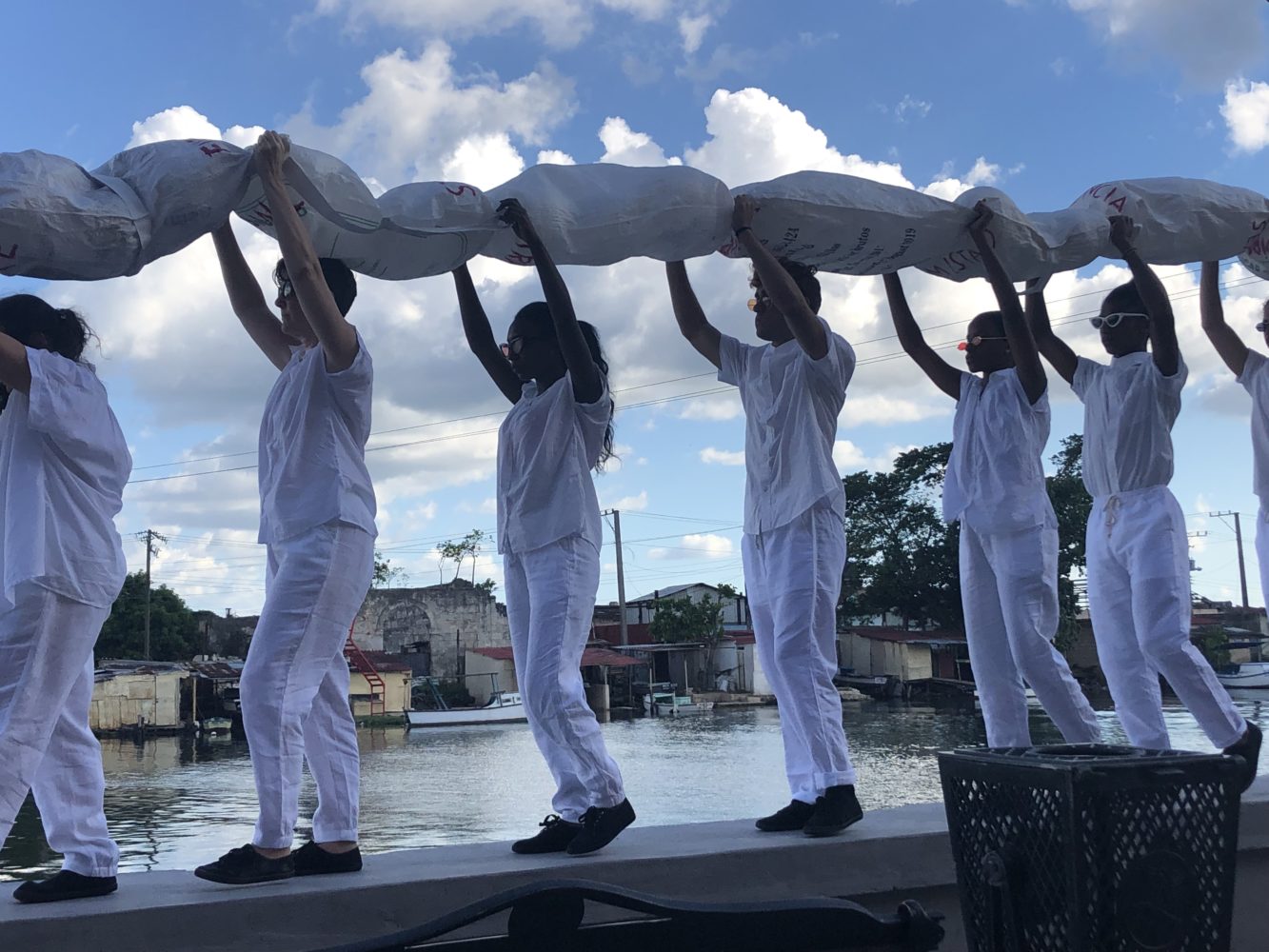

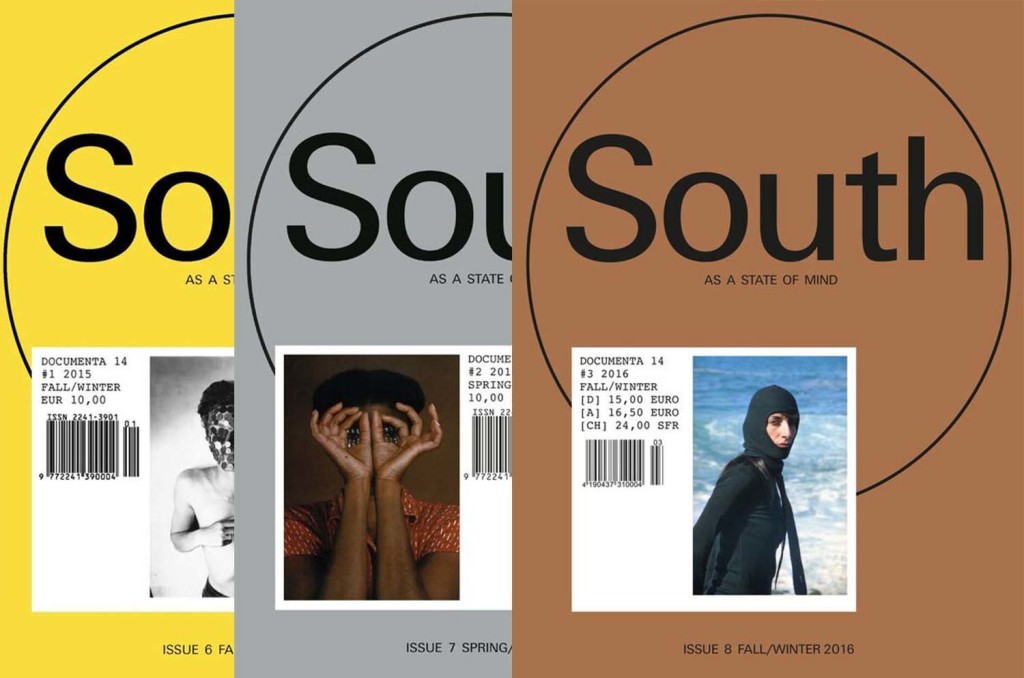

Within the sphere of contemporary art—another economy being stretched to its limits by the forces of globalization—artists, scholars, and curators are undertaking initiatives to decentralize conventional, historical systems of power. As part of the 13th Havana Biennial earlier this year, Cuban-born, Nashville-based artist Maria Magdalena Campos-Pons curated exhibitions, installations, and performances in her hometown of Matanzas, a small city located an hour and half’s drive from Havana. While accompanying Campos-Pons and other artists from Nashville and across the South during their time in Matanzas, I met curators Allison Glenn and Marina Fokidis. Glenn’s research at the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas—where she is associate curator of contemporary art—seeks to uncover histories that elucidate the roles played by Latin American independence movements in the development of the American West. Fokidis, who served on the curatorial team of documenta 14 and curated the Greek Pavilion at the 51st Venice Biennale in 2003, publishes critical conversations about art and power in the biannual magazine she initiated, directs, and co-edits, South as a State of Mind. In this conversation, both curators consider their work in relation to narratives of the Global South, recount successful and less-than-successful attempts at decentralizing cultural power, and imagine a future beyond globalized binaries and divisions. Our conversation was conducted over WhatsApp in June 2019 and has been edited for publication.

Sara Lee Burd: Allison, what have you found while investigating intersections between the Global South and North in the American South? What is the role of art in creating conversations around globalism and the effects of neoliberalism?

Allison Glenn: I’ve embarked on a research project that I hope will become an exhibition. The research that I’ve been doing—and what I’m hoping to explore through artworks, artists, and ideas—is how the development of the United States west of the Mississippi was made possible through various independence movements in Latin America. My research is focused on really shifting the way that we talk about the development of the United States, and subsequently, the development of American ideologies like manifest destiny, the American Dream, and western expansion. I should specify that when I use the word American, I am specifically referencing the United States. I am relying on the slippage of the word American and how it is used in the United States to refer to this country, while acknowledging that, in actuality, we are part of this larger system of the Americas. I would like to consider how the Global South, if we want to call it the Global South, has influenced the development of the American West.

I am attempting to shift histories to incorporate artists and artworks that engage with a more expansive purview, which can tell a more comprehensive story about the United States. It’s possible to consider how the culmination of the Haitian independence movement made the acquisition of the Louisiana Purchase territory possible. We can talk about the Puerto Rican independence movement and the tenuous relationship Puerto Rico has with the United States. That’s where I’m at right now with this question around globalism, the Global South, and the American South. It’s rooted in language. It’s also rooted in the telling of histories and the way the narrative of history should and can be reframed to have a broader, more comprehensive view that includes the Global South and makes connections between the American South and Global South—specifically linking to the Caribbean.

SLB: I’m interested in how new conversations surrounding colonialism and Indigenous histories have developed in the American South. Could you provide an example of how curators or artists have addressed narratives that overlook the effects of colonialism on Indigenous cultures?

AG: I have a colleague at Crystal Bridges, Mindy Besaw, the museum’s curator of American art. Mindy was one of the co-curators for an exhibition called Art for a New Understanding, a group exhibition that included contemporary Indigenous and Native American artists living in North America. Her co-curators were Manuela Well-Off-Man and Candice Hopkins. During this exhibition, Mindy was instrumental in an acquisition of Edgar Heap of Birds’s Native Host series that is currently installed in our Orchard Trail. This project is about land acknowledgment, the practice of naming and acknowledging the tribes that existed on the land that you’re currently occupying and thanking them prior to beginning any public event. We have a practice of acknowledging the heritage of land before events at Crystal Bridges. Similarly, with his Native Hosts signs for the museum, Edgar Heap of Birds identifies and acknowledges tribes that occupied the land that we now call Arkansas.

As outdoor sculpture falls under my purview at Crystal Bridges, I worked with Heap of Birds to site and install these works. Native Hosts are text-based artworks that resemble road signs on which Heap of Birds includes the name of the state where the signs will be located, along with the names of the tribes that occupied this land prior to colonialism and settlers. On these signs, Heap of Birds visually reverses the name of the state where the signs are located, showing it as though the text were being viewed in a mirror. This reversal is an opportunity to resist how colonialism has framed and used language to talk about occupation of land in a way that denies the presence of the Indigenous communities that were there prior to the colonizer. By reversing the name of the state, he pulls the viewer back a bit. It de-centers and destabilizes. The seven signs of the Native Host series at Crystal Bridges provide an opportunity for the artist to raise awareness of the Mississippian tribes that occupied this land prior to the Louisiana Purchase.

It’s been wonderful to really witness the way that Mindy has approached telling the story of American art through Indigenous objects and expanding the story about what America is through acquisitions like this. She’s reinstalled the early American galleries to include Indigenous artworks and artifacts alongside historical paintings to tell a story of American art that includes the Indigenous population that existed before America or the idea of America existed. That’s really something that dovetails back to this idea of American South, Global South, or the Americas. These are also larger questions that I am considering as a curator at an American art museum, really thinking critically about what American art is.

Marina Fokidis: I wanted to say something in relation to what Allison is saying, which is very interesting to me. This idea of acknowledging the land is very beautiful. Actually, this week I was discussing this with Pip Day [director and curator of the SBC Gallery of Contemporary Art in Montreal]. The museum was hosting Wood Land School (an Indigenous art collective from Ontario) in 2017. They somehow inverted the whole idea of governing a museum, because they gave its governance to an Indigenous collective who could change everything, even their policies. They kept and ran the museum for one year, really changing its politics and the policies. What I find extremely interesting in that part of this programming decision is sharing situated knowledges, as opposed to the fetishizing like Allison was saying.

SLB: These examples present successful attempts to change fixed narratives in art and history. Do either of you want to share an example of how attempting to create new lines of investigation has failed?

MF: I don’t want to go to specific examples, but I think instead of being in an American museum and interrogating what the land of the Americas is, we’ve seen a lot of fetishizing of Indigenous communities from non-Indigenous curators—in order to somehow clean their conscience—but we sometimes also see this happening with Indigenous curators, who are often attempting to somehow fortify the general knowledge around various Indigenous communities. This is legitimate, but sometimes in other cases this is done to just create an art market, which is also legitimate within the capitalist context we live in. I wish it weren’t like that.

I think what Allison was telling us is a beautiful example. In my mind or my utopian ideas, Indigenous knowledge exists not just as a memory but also as a score on the future, as we failed with the “western” canonical system that we adopted and follow. You understand? Very often, situated and neglected knowledges are much more pertinent for their localities and beyond. If we follow these knowledges in each respective locality and create a series of new interlocal networks, then we have the chance to maybe reach a fresh “universal,” polyphonic, new/old wisdom that might save our planet.

SLB: What is the relationship of Greece to the Global South, Marina? How does this influence your work?

MF: Europe is considered the North, of course, vis-à-vis the Global South, which contains everything beneath the equator—a conglomerate of territories that share colonial processes and colonial history. By default, as a European, it is assumed you are Northerner, a colonizer, but this is not always true, as in the case of Greece, for example.

Of course, not all European countries were colonizers at all, as in the case of Greece and other countries, mostly in the Balkans—let’s call them the weaker states. They were also colonized by the Ottoman Empire. Of course, it was a very different story because they were not Indigenous people, so the Ottoman Empire took over the Roman empire. There were a series of many empires. It was another form of globalism, apart from the fact that taxes were paid to one head, which was the Ottomans and the Sultans.

Now, going back to the South and the idea of starting the journal South as a State of Mind. In 2010, I was the director of a team that founded an independent institution, the Kunsthalle Athena, and we started the publication a couple of years later by looking closer into shared interests and affinities with other places around the world where the sun always shines, which somehow do not entirely fit into the prevailing western canon.

The beginning of the crisis in Greece was somehow felt towards the end of 2008, through youth demonstration and riots with fires. At that time the so-called “great powers”—Germany, France, England, nations with strong economies—started dividing Europe. As a result of the Greek crisis, Greece became part of Southern Europe. Before it was never proclaimed as such. We were considered part of east Europe, or the Balkans, or the Mediterranean Sea, but the name “South Europe” was never in the foreground, or we did not belong to it. Then the term PIGS made its appearance as a legitimate abbreviation for Portugal, Italy, Greece, and Spain—imagine! It was used in the European parliament and also in the Financial Times and other newspapers. We understood that South was used as a derogative term, of course, against people that cannot be obedient to a kind of westernized way of being in the world, including economizing or leading, let’s say, a more Protestant way of life.

SLB: The two of you presented your work and research on intersections of the Global South and the Global North at a panel discussion in Matanzas, Cuba, as part of the 13th Havana Biennial. What did you learn from considering Matanzas as a case study for decentralizing cultural hierarchies?

AG: I feel like what Magda did in Matanzas was a really wonderful example of decentralizing. My understanding of and relationship to Cuba shifted with Magda’s inclusion of Matanzas as a second site for the Havana Biennial. Oftentimes, the idea of Havana eclipses Cuba as a country. That is, when people think of Cuba, they think of Havana, but there are many other cities in Cuba with just as rich and varied histories. The inclusion of Matanzas also allowed me to have a greater sense of the Afro-Caribbean histories of Cuba, more directly linking the country to both the Haitian independence movement and the American South. I think that more curatorial, artistic, and art historical approaches that decenter places and repositories for knowledge—whether they’re cities or universities or institutions—that’s the way toward the future.

MF: What happened in Matanzas vis-à-vis Havana was that Matanzas became a nucleus on its own. Matanzas was a parallel song, melody, rhythm, and it was quite loud, sovereign, and strong in itself. As a separate entity, and through the efforts of Magdalena Campos-Pons, it gathered quite important people from the so-called art world. Matanzas was not just a small satellite of Havana Biennial or just an addition to it; it had and has a huge impact on its own. It is like a miracle—I think this is a little bit what Allison is saying too. I think we should follow the score of Matanzas’s multiplicity, allowing room for even more voices to join the equation of a biennial. Giving room to lots of voices, as many as we can—because only a large variety of diverse voices, some of which had no agency before—will destabilize the “one and only” centralized authority.

SLB: How do you propose we balance power between the Global North and South?

MF: Going over the borders of national sovereignty and national relationships between countries. Finding shared affinities within smaller communities. For example, now we are recalling our meeting in Matanzas, and we are conversing about it, so we are forming a union. What is the relationship between Matanzas and Athens, or Matanzas and Nashville? It is something that can be eventually defined in a set of concrete sensitivities and ideas and not only in the imaginary realm. Starting to make different kinds of connections like these might help us in bypassing the governing powers—and eventually cancel them. As our interlocal connections get stronger and our interlocal network bigger, maybe we will be able to break the monopoly in this all-encompassing system, which is somehow supported by the global economy. At the moment, global power systems have even adopted the resistance within them. The moment there is a community or a movement of resistance, there is also an offer for its funding from public or private global funds—this is the way it is basically controlled.

AG: It’s the push against an expansive way of thinking, because all of these—globalism, narratives about the Global North and the Global South, colonialism, neoliberalism—really require an aversion to information sharing, an aversion to a decentering. What is required is a more rhizomatic approach to information and identity, all of that. The dominant narratives of power require linearity and one-dimensionality in order to exist.

Allison Glenn, along with curators Lauren Haynes and Alejo Benedetti, is organizing State of the Art II—a follow-up to the survey of American contemporary art of the same name presented at the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in 2014—set to open in Bentonville, Arkansas, at the museum and its affiliated contemporary art center The Momentary in February 2020.

Read past issues of South as a State of Mind, the biannual magazine initiated, directed, and co-edited by Athens, Greece-based curator Marina Fokidis.