In his controversial notion of “Third-World literature,” first outlined in an essay published in 1986, Marxist cultural theorist Fredric Jameson argues that a certain subset of literature—that of nations problematically characterized as belonging to the so-called “Third World”—projects an inextricable political dimension on the individual, always narrating personal experience as a form of national allegory. Where others may have inserted the term “Third World,” contemporary discourse tends to use the language of the “Global South,” a term that originated in writer and activist Carl Oglesby’s 1969 description of American “dominance of the global south” in relation to the Vietnam War. Shortly before the collapse of the Communist Bloc in 1989, an event some historians mark as the end of such thinking in terms of “worlds,” filmmaker and theorist Trinh T. Minh-Ha wrote—in a special issue of the journal Discourse focused on “Third-World women”—that “there is a Third World in every First World, and vice versa.” With Minh-Ha’s formulation in mind, it’s possible to argue today that there is a South in every North, and vice versa.

This is perhaps especially apparent in the context of the United States, where the American South occupies a distinct position in the country’s cultural and political history. Not coincidentally, documentary art in the United States owes a tremendous debt to the South, where the form first emerged and flourished, becoming imbued with the region’s political and historical nature over the past century and half. Documentary art has in many ways become an allegorical form for portraying life on the margins of society, in the American South in particular and the Global South more broadly.

This idea is borne out by tracing connections between some major moments in the history of documentary art in the United States. The Civil War (1861-1865) was one of the first conflicts to be extensively photographed; the origin of documentary art in the U.S. is defined by the war, particularly in the photographs of Matthew Brady. When Brady was making photographs, photographers were still using wet-plate cameras and Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain (1917) was a half-century away in the future. Curiously, documentary art has demonstrated its capacities for a sort of conceptual afterlife since its inception. At the conclusion of the Civil War, Brady was forced to sell most of his glass-plate negatives to settle his debts, and, according to documentarian Ken Burns, the leftover glass negatives were recycled to build greenhouses. As years passed, the sun’s rays would burn away the images from the glass, destroying the negatives. Considered from the present moment in art history, this sounds more like the process behind a site-specific art installation than a historical incident. Inspired by the story, North Carolina-based photographer Harry Taylor created ambrotypes based the fabled negatives as components for his installation Requiem in Glass: Brady’s Greenhouse at Wilmington’s Cameron Art Museum in 2014.

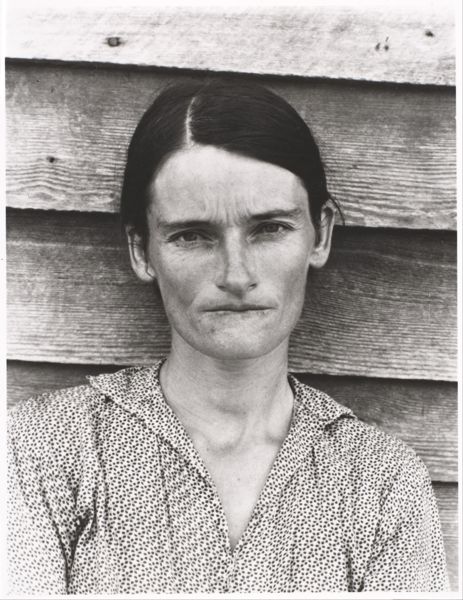

In the 1930s, largely as part of the photographs commissioned by the Farm Security Administration, the American South became the subject of outright documentary conceptualism in the photographs of Walker Evans. By solely categorizing him as a social documentary photographer in line with, for example, Dorothea Lange, many viewers actually misunderstand Evans’s work when they first see his photos. Because of the complex linguistic acrobatics he portrayed, Evans was the South’s first conceptual photographer. His work is marked by an indexical, even deadpan stylization of the documentary form. His photographs of text, appearing in forms such as street signs and advertisements, are, in retrospect, forbearers of Pop Art.

As part of the Pictures Generation of the 1980s, artist Sherrie Levine used photography and photographic archives to investigate questions of representation, power, and appropriation. In a Duchampian conceptual move, she took photographs by Walker Evans first published in the 1941 book Let Us Now Praise Famous Men and rephotographed them forty years later, highlighting photography’s historically male-dominated canon and complicating traditional understandings of authorship, authenticity, and artistic value. Levine’s approach augured a new trend in documentary art: an obsession with the document itself. From the perspective of Trinh T. Minh-Ha’s claim that “there is a South in every North, and vice versa,” Levine’s work illustrates how marginalized identities exist in many different contexts throughout the world, conceptually extending the notion of the South more globally, beyond the Mason-Dixon line, to geographies and identities defined by any prescribed binary or dichotomy.

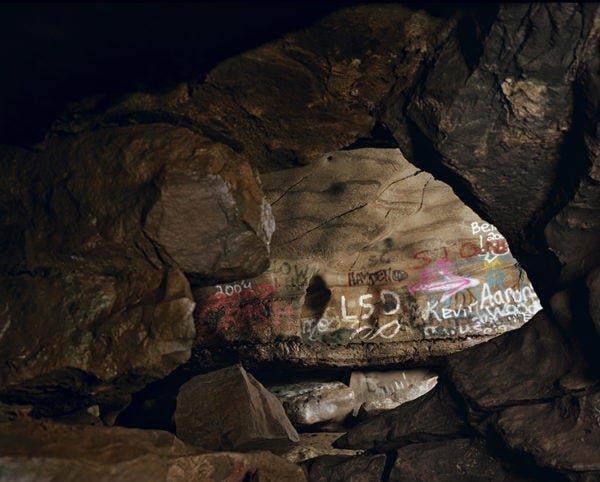

Documentary art has continued to evolve since Levine’s appropriation of Evans’s photographs—an event which, at this point, itself took place over thirty years ago. Artists have become more reflexive and capable of tackling issues that project the narratives, images, and dynamics associated with the American South on a global stage. In 1999, An-My Lê began working with Vietnam War re-enactors in Virginia and North Carolina for her Small Wars series. The photographs in the series prompt a double take, causing you to wonder whether you are looking at an authentic document of the Vietnam War or a recreation of one, disturbing the boundaries between historical fact and fiction. Jeff Whetstone’s 2008 series Post-Pleistocene is comprised of trippy photographs of graffitied caves in the South, referencing the origins of art in the cave paintings of Lascaux, hideouts along the Underground Railroad, and Plato’s Allegory of the Cave. Interestingly, both Whetstone and Lê use large-format cameras for their respective series, creating a technological and perhaps spiritual connection to their predecessors Walker Evans and Matthew Brady. Both contemporary photographers also print their images in extremely large formats, promoting a sense of submersion in the sublime that is relatively new to documentary art.

In light of the historical and conceptual relationships between the American South and documentary art in the U.S., an alternative understanding of documentary art could be proposed—one focused on exploring margins, boundaries, representation, and power, rather than aspiring to serve as a moralistic social conscience. In this sense documentary art continues to function as an allegory for the South, but a South that is capacious and mutable enough to contain many different narratives, images, and perspectives.