We are in the middle of a vacationless summer.

This season, usually marked by day trips and carefree weeks on the beach, has been brought to a static lull by the current pandemic. Theme parks and pools across America have shuttered, and necessary health precautions have made formerly day-drunk weekends into more sobering affairs. Though the very idea of vacation may seem like a far-off dream this year, the economic system created by the gargantuan entertainment industry in states like Florida still remains—bloated and useless, leaving workers in freefall.

Florida’s recreation industries have fueled both the state’s economy and its wildly romanticized place in our popular imagination. More than in any other state, capital and the ideals of leisure are interconnected in Florida; the tourist industry and its various offshoots around the state have been so intricately woven into the common rites of American life that it is difficult to achieve a sufficient critical distance to analyze them or account for the ways in which our own fantasies have built their extractive economies. How can we begin to analyze the ways in which we are accomplices in this system—through spring breaks, family trips, and other sojourns that we see as integral parts of not only growing up but the American experience writ large?

The protagonists of many Florida-set films of recent years have found themselves in the middle of this brutal economic struggle. In films ranging from indie darlings to provocative dramas to acclaimed dramedies, the plight of Florida workers and their role in the state’s tourism and entertainment industries is situated front and center. Twenty-first-century Florida epics such as Magic Mike, The Florida Project, and Spring Breakers explore the money and mythologies driving Florida’s leisure economies but ultimately avoid interrogating them. These films’ vivid aesthetics and their flawed, romanticized understanding of class in America hide away the nasty truths of Florida’s vicious economy and further distort the lives of the very people they claim to celebrate.

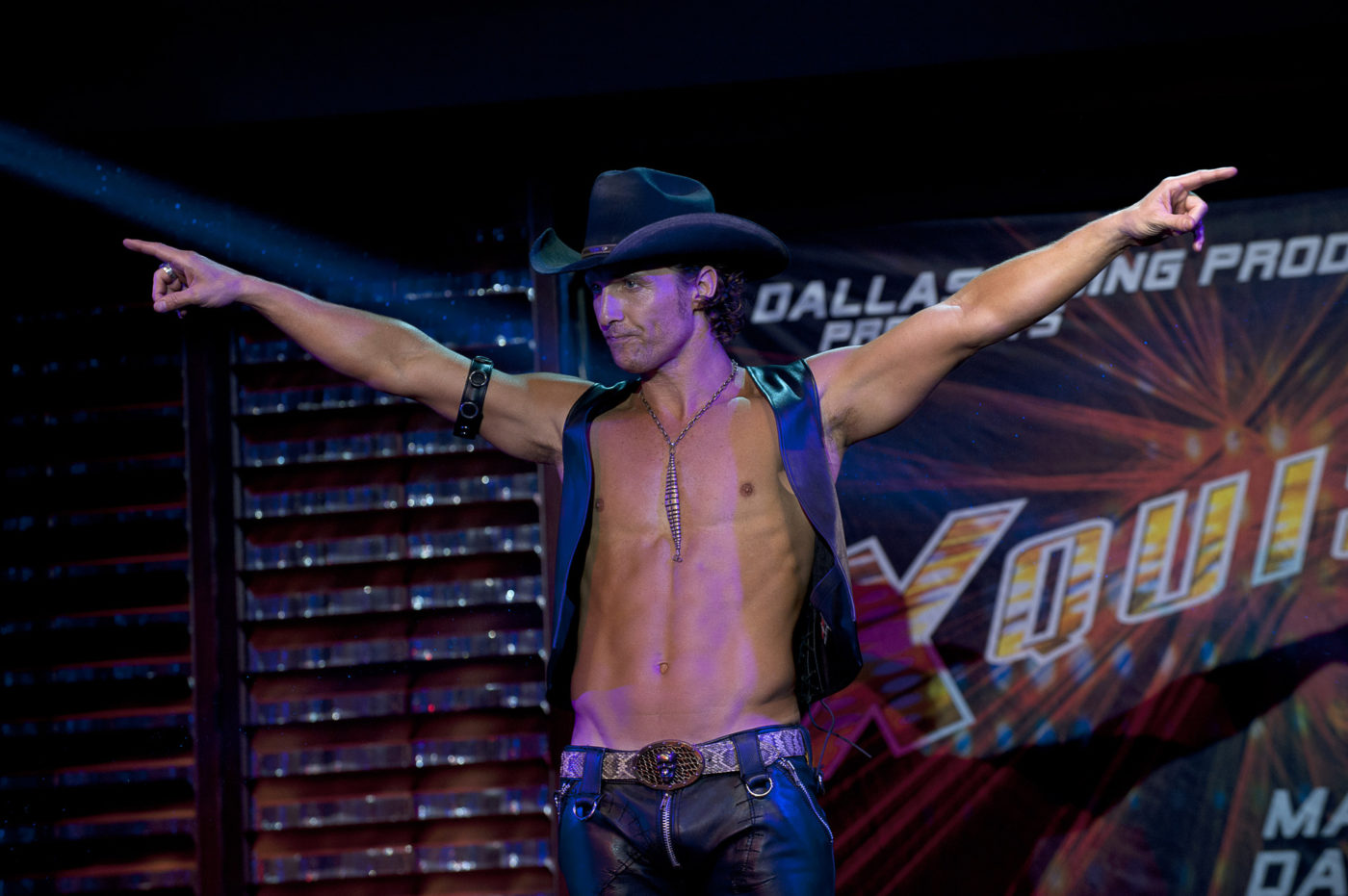

Steven Soderbergh’s 2012 stripper saga Magic Mike follows Mike, a successful stripper at Tampa’s Xquisite Strip Club, and an aimless young man named Adam (affectionately called “the Kid”), who Mike brings into the club after meeting him at his construction day job. Amid tensions with Xquisite’s scheming owner Dallas, Mike is becoming increasingly disillusioned by stripping, confiding in Adam that he’s saving up to open a custom furniture shop. Adam, on the other hand, is intoxicated by the lifestyle stripping affords him, indulging in the ecstasy that Xquisite’s DJ supplies him. After a disastrous party that results in Adam losing $10,000 worth of drugs, Mike uses his savings to pay off Adam’s debts and leaves the industry for good.

Set in the Orlando suburb of Kissimmee, The Florida Project (the 2017 Cannes hit from Tangerine director Sean Baker) portrays the same push-and-pull for power within the seedy entertainment economies of South Florida through the eyes of the residents of The Magic Castle, a decrepit motel on the border between Disney World and the economic vacuum it created. Six-year-old Moonee and her young mother Halley live at The Magic Castle with other poverty-stricken, transient families on the brink of homelessness. The Magic Castle’s proprietor Bobby does his best to care for the now unemployed Halley and to keep the riotous Moonee out of trouble in her mother’s absence, but after the Florida Department of Children and Families finds out that Halley has been soliciting sex work while living at the motel, social workers come to take Moonee into their custody. The film ends on an ambiguous, fantastical note with Moonee breaking free from the social workers and running away to Disney World’s Magic Kingdom with a friend.

Showcasing crumbling technicolor buildings and neon lights in the bright Florida sunshine, these films use aesthetic wonder to craft their narratives and give viewers an experience of the ritualistic pleasure of a childhood trip to a theme park or a wild night on vacation. The depictions of Orlando suburbs in The Florida Project and Tampa in Magic Mike rely on an undeniable sense of place—the wild, lawless Florida energy that both films possess—that invokes memory and nostalgia. These qualities appear in the first minutes of The Florida Project as Moonee and fellow motel kid Scooty are seen giggling against the blindingly vivid purple walls of The Magic Castle, a garish but well-intended attempt by Bobby to clean up the establishment. Instead of intimate scenes that provide more of a sense of these characters and this place, Baker defers to technicolor shots of their Kissimmee neighborhood and the over-the-top façades of the gift shops that line the main strip—familiar to anyone who has spent a too-hot summer in the state. The moments of emotional clarity onscreen occur when the settings are unvarnished and divorced from any sort of entertainment, such as scenes of Halley and Moonee’s late nights in their room, where we see their love for each other, or during a vengeful morning sojourn to Waffle House to antagonize an ex-friend of Halley’s.

Much like Bobby’s attempt to paint over his motel’s flaws (and Florida lawmakers’ attempts to cover up vast inequalities with visions of paradise), the beauty of the setting of The Florida Project is abundant but only serves to distract from the people at the center of the poverty created by the sprawl Baker depicts. In her review of the film for Film Comment, Cassie da Costa writes that the director’s unwillingness to address the plight of this specific poor community and instead defer to spectacular shots of the motels creates a “level of distance” between Baker and his subjects, depriving the film and its characters’ of any genuine heart. Even more sinister, da Costa reads the characters’ lack of development or depth as a lack of Baker’s empathy and understanding of the conditions and systems that have shaped the circumstances of Moonee, Halley, or even Bobby’s lives: “[the] audience is invited to believe that [the characters’] lives are devoid of thoughts and motivations beyond hustle and pleasure, and so the movie ends up feeling like a millennial Instagram feed: cute, edgy, explosive, pithy, but shallow.”

The aesthetic beauty of Magic Mike comes from one thing and one thing only: celebrity men with chiseled abs in various states of undress. As viewers, we are more acquainted with a straight male gaze that prioritizes an easily accessible and marketable female sexuality. The gaze here is notably calibrated toward people attracted to men, but Soderbergh crosses the line from pleasure into pure spectacle by making the very act of watching inescapable from the pleasure object. As the director and cinematographer, Steven Soderbergh frames these scenes to position his viewers as though they were in the audience at the club, using the strippers’ performances as central plot devices and shooting these scenes so that the stripping is central to the plot (and portrayed as the characters’ livelihoods—acknowledging sex work as actual labor). But, as in The Florida Project, it becomes difficult to distinguish between aesthetic pleasure and callous, empty spectacle. The cinematic gaze in Magic Mike implicates the viewer in the act of going to a strip club, placing them in the middle of a ritualized event. In the audience of Xquisite, we see bachelorette parties and sorority sisters, visually establishing going to a strip club as a rite of erotic passage. The sweat, lights, and glowing, superhuman bodies bring the viewer into a pseudo-ceremony, but the ceremony itself is never questioned.

The visual spectacles of The Florida Project and Magic Mike distract from what truly defines their failures in terms of socioeconomic critique and understanding—the films themselves operate within a wretched consumerist framework that is revealed as hollow and artificial through the very stories they tell. In real-life Orlando, Halley and Moonee’s life at The Magic Castle isn’t far from the reality for many people who work in and out of nearby theme parks and clubs. Increasing rents and arbitrary requirements set by landlords have forced many to live in long-term stay hotels like the motel in The Florida Project, even with local efforts made by unions like Unite Here 737, which represents nearly 40,000 service workers and cast members at Walt Disney World.

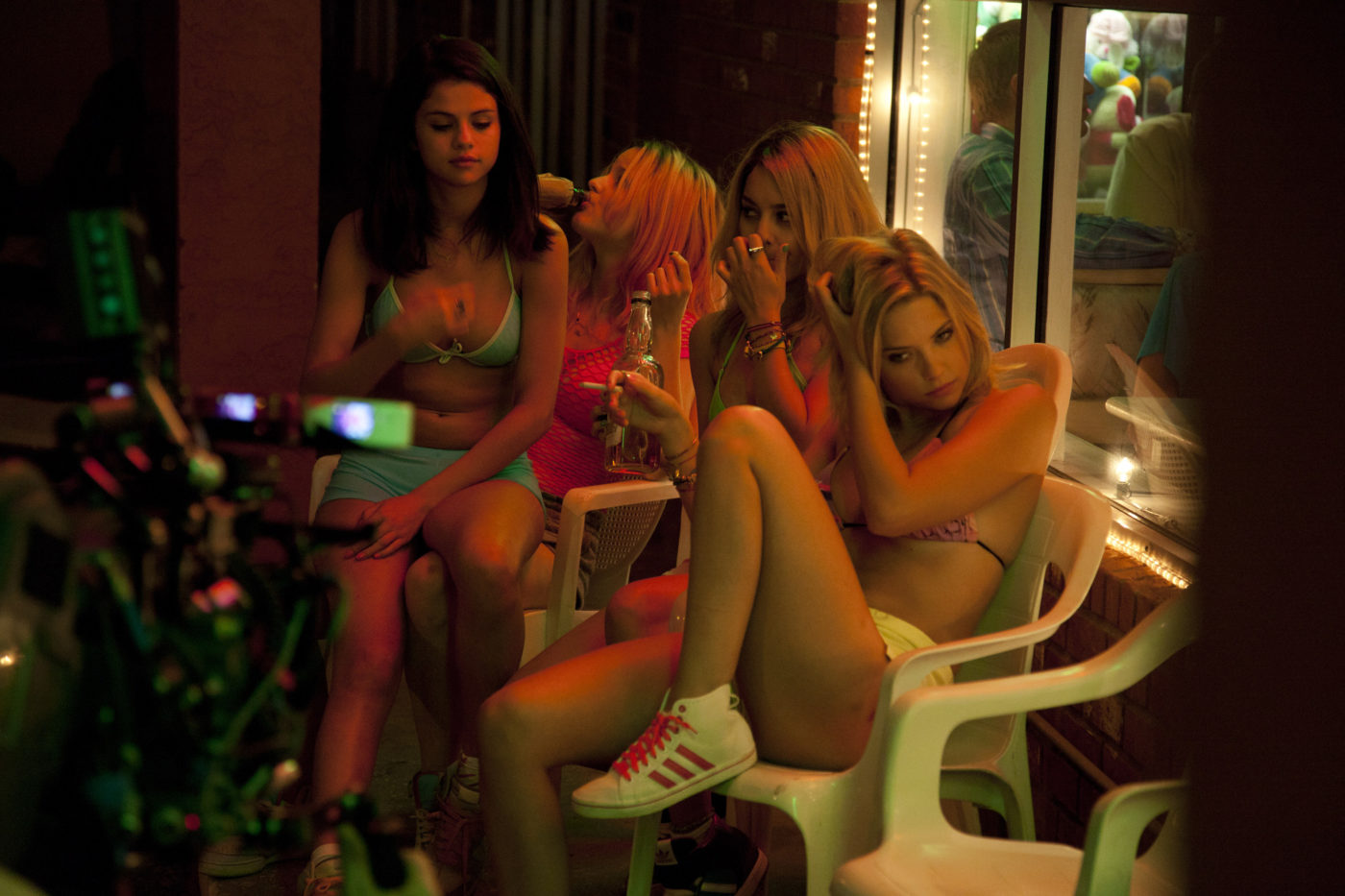

Florida’s unholy amalgamation of recreation, capitalism, and the routine desires of the American imagination is on full display in Spring Breakers, Harmony Korine’s 2010 film about four young women desperate to go to St. Petersburg during a college spring break. To fund their trip, they rob a local restaurant with seemingly little remorse and head to the beach for a week of bacchanalia. After their arrest for public intoxication, the girls are bailed out by the local rapper Alien, who quickly brings the girls into his arms-and-drug-dealing scheme, using them to help retaliate against a local gang led by Big Arch (played by none other than Atlanta trap icon Gucci Mane). After two of their fellow travelers depart for fear of the violent escalations of their actions, the remaining spring breakers join Alien in one final and bloody act of revenge against his rivals. Afterwards, the vacationing girls eventually leave Florida, seemingly oblivious to the carnage and catastrophe they’ve left in their wake.

Even though the plot of Spring Breakers veers toward the extreme, the motivations and fantasies of its characters are all too familiar. The rituals of thoughtless consumption are most apparent in the film’s most visually stunning scenes, including its climax, when the two final girls call their mothers from a gas station. They describe the trip as a dream, a nearly spiritual experience in paradise that made them aspire to be better people. Their conversations are played over a flashback from earlier in the night, when the girls invaded Big Arch’s compound, killing everyone inside. The blood-soaked scene is played for subversive but hollow contrast (as is the style of Harmony Korine), but what their voiceover narrative reveals is how their pursuit of Florida’s pleasures and vices exaggerates the willful ignorance of many visitors to the state. Further along in the scene, the flashback and voiceover give way to a montage of shots featuring Big Arch and his associates’ dead bodies contrasted with the spring breakers drinking and dancing on St. Petersburg’s beaches. As in The Florida Project, these aesthetic gestures attempt to form a grand statement about American culture and its hedonism, but the comparison is too contrived, shockingly callous in its failure to imagine Florida as anything more than a charged setting for overwrought cinematic fantasy.

In the growing canon of Florida films, the working poor of the state are often placed front and center, an ironic contrast with their relative powerlessness in reality. While reflecting the difficulties of living in an economy overrun by parasitic businesses and tourist schemes, these films largely fail to understand their characters’ motivations and desires by neglecting to confront the ritualistic, fantasy-driven aspects of Florida’s recreation industry that make such poverty and powerlessness endemic in the first place. The stories of workers seen in Magic Mike and The Florida Project are not purely fiction—and neither is the tourism-fueled recklessness of Spring Breakers—but these films get further and further away from the truth in their unwillingness to imagine a society free from the bloodthirsty dynamics and faulty idealism of the American Dream.

This essay is part of Burnaway’s yearlong series on States of Leisure.

Find out more about the three themes guiding the magazine’s publishing activities for the remainder of 2020 here.