Donna Woodley is a Nashville painter whose obsession with faces extends beyond the surface. In painting people she knows, she represents their emotional states–who they are and why they are. On the way there, she brings up a host of other issues: internalized attitudes about race and gender, assumptions we make about names, and what W.E.B. Dubois described as double-consciousness.

Woodley paints portraits of women—herself, friends, and colleagues—and the portraits pulse with tension. While each contains a sense of strength and empowerment within the subject, each also has the sense of the subject seeing herself from the outside, through the eyes of another. It’s a dynamic that is as old as portraiture itself, but Woodley’s choice to mainly paint women of color—who are often at the intersections of multiple oppressions—carries added weight.

She plays with names, too. Her series Black Women Rock: Painting the Black Female Experience is titled with black women’s names coupled with distinguished titles, so you get Shawntae the Corporate Attorney and Wanisha the Neurologist. As she typed these names in Microsoft Word, she noticed the inevitable red squiggly line beneath them–Microsoft’s tiny suggestion that the black names are misspelled, incorrect. The electronic dictionaries designate these names invalid.

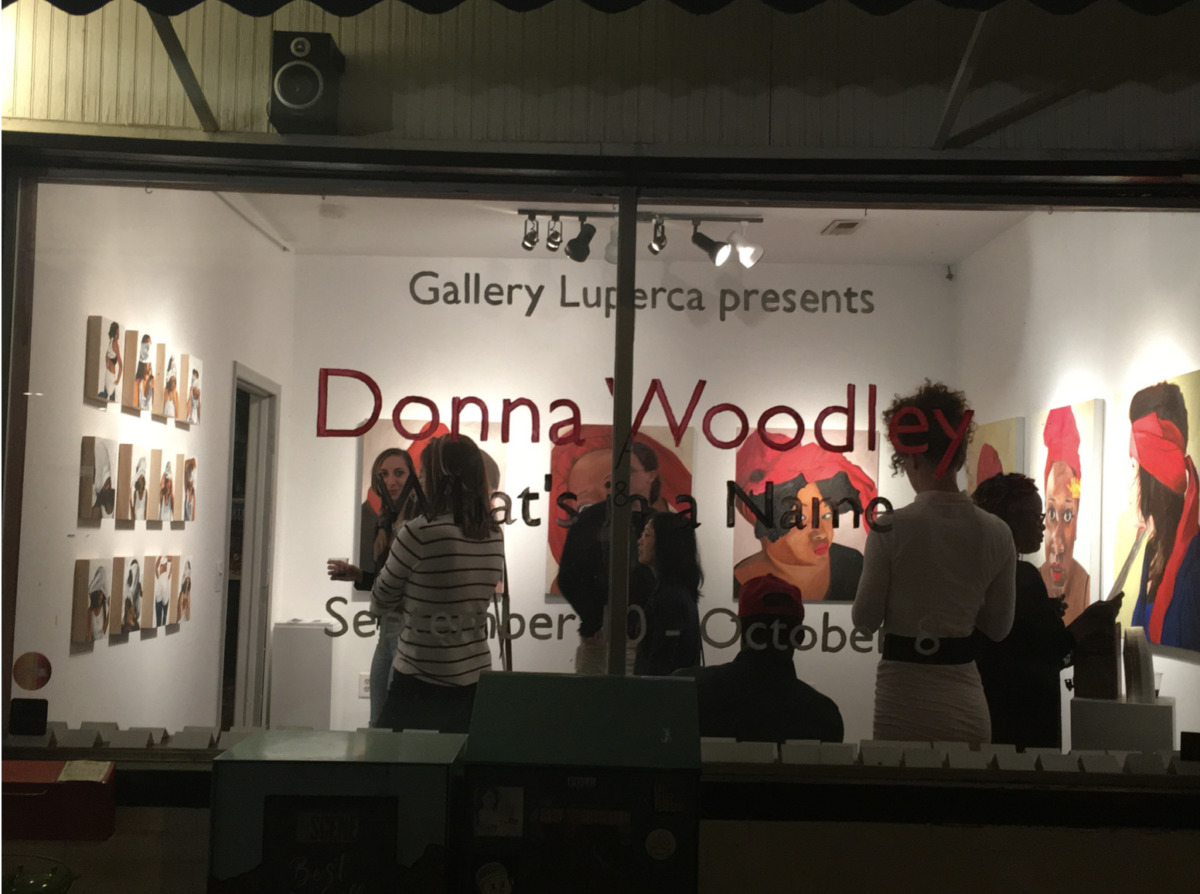

In her current show “What’s In A Name?” organized by Gallery Luperca in Nashville, Woodley printed out over 80 seating place cards. Each has a woman’s first name—Emily, Cornisha, Monique—and the last name of an historical United States politician. Lined up together, they make for an interesting dinner party with Louiska Adams, Becky Monroe, Thomastica Cleveland, and Morgan Garfield. Her point is when we invalidate the names of black women, we invalidate their experiences and their potential. Woodley suggests that if we can’t imagine a Tramaine Van Buren in the Oval Office, then perhaps the problem isn’t with the name itself but with our implicit bias.

The owners of Gallery Luperca, Katie Wolf and Sara Lederach, announced some months ago that their building was going the way of the construction cranes, i.e. changing hands to be “developed”—into what, I don’t know. Right now, Nashville is both a developer’s wet dream and a precarious hamlet for artist-run spaces, and the city seems to be making up its mind about what it will become. But Wolf and Lederach had to vacate the building faster than they had hoped. Having already planned for “What’s In A Name?”, the two pulled off a heroic feat by transforming a supply closet at Fond Object, an East Nashville vintage shop, into a small gallery that was just perfect for Woodley’s eight 30 by 36 inch paintings. The moral of the story is that Nashville may be selling its soul to developers, but it’s still got a lot of heart.

I spoke to Woodley in Nashville.

Erica Ciccarone: Why are you drawn to portraiture?

Donna Woodley: I’ve always had an interest in the emotional state of people as a whole, their stories, and their physical attributes. I’m curious about why we are the way we are as humans. How did we come to be ourselves? Alice Neel painted many, many portraits and had the extraordinary ability to capture everything that embodied her sitters during the time she painted them. I could stare at her paintings for hours. My interest in people and their stories drives me to paint portraits. When I am doing photoshoots for reference material, I tend to ask questions about my models’ lives. While they’re talking, I just listen and take pictures. If I see something, I yell, “Don’t move!” so that I can seize that moment. This process almost always allows me to capture the images and emotions that carry forward into my paintings.

EC: Contemporary portraiture is dominated by Black artists right now, and rightfully so. Kehinde Wiley, Mickalene Thomas, Fahamu Pecou, and Beverly McIver all come to mind as your predecessors. It strikes me as critical that people of color are being visible in arts institution, not only as artists but as subjects of paintings. Thoughts?

DW: I agree that it is critical that people of color, particularly black artists, maintain visibility as makers and subject matter. The perspective of black male masculinity, hip hop culture, and the history that upholds these ideas is often relayed in the paintings of Fahamu Pecou and have been key in benefiting American and pop culture from an economic standpoint for years. Mainstream America has consistently snatched concepts such as rapping, twerking, or even stepping, only to reassign and integrate them into pop culture with virtually little to no acknowledgement of their origins. Most recently, a popular fashion designer adorned his models with dreadlocks and cited Boy George as his source of inspiration. Meanwhile in Alabama, an appeals court says that employees do not have the right to wear dreadlocks and ultimately can be ruled out for a job with no recourse if their hair is dreaded. That’s just one recent example that confirms that the work and discourse about black experience by black artists is essential for viewers and readers.

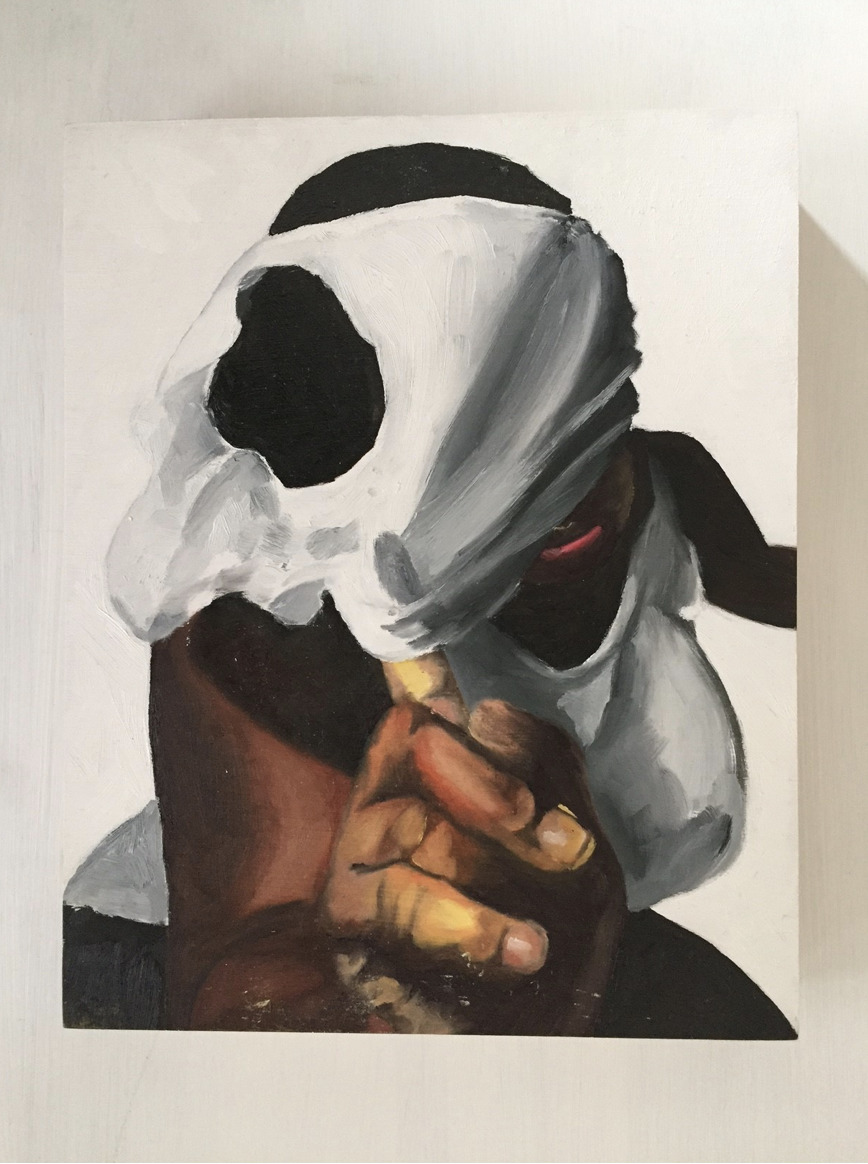

EC: Let’s talk about your previous series “Black Women Rock: Painting Black Female Experience.” You painted portraits of your friends wearing granny panties on their heads, often covering their eyes. Why did you make this decision?

DW: The initial decision derived from a discussion that I had with an artist friend surrounding absurdity and humor in art. I had dealt with granny panties in some of my previous graduate work and wanted to revisit them in a more absurd way. When I started to explore black women in American culture, ideas of invisibility and visibility surfaced. I remembered conversations that I had with my black girlfriends about sometimes feeling invisible in this society and wanting to cry out to be noticed. The tension between a black woman feeling invisible versus her doing something absurd in an attempt to be noticed in any given environment became very interesting to me. It was a notion that I’ve felt, experienced, and witnessed. So I decided to paint my black female friends with granny panties covering their eyes to represent those ideas.

EC: Black American women have been historically sexualized and fetishized by white culture, and this objectification has spilled over into hip hop culture as well. Do you see an extension of this in portraiture? Do you feel like you’re resisting this in your own work?

DW: I think it depends on the medium. While Mickalene Thomas’ photographic portraits and narratives may generate discussion surrounding the sexualization and fetishization of black women, her paintings seem to relay something very different. And I’ve not seen very many portrait paintings of black women in galleries and museums similar to the portraits of John Currin or Lisa Yuskavage. For me there is a natural resistance to it in my work because I’m shy, but I am also very curious about what exploring this topic could look like. I believe that while there is a distinct difference between falling victim to sexualization/fetishization and exploring the idea in a painting, the lines can get crossed. The notion of the lines crossing is my curiosity.

8 by 10 inches

EC: Naming figures prominently in your work. In “Black Women Rock,” you titled the paintings with names like Ushika the Marketing Director and Trasheena the 5th District Councilwoman. Why do you think names hold so much power in social consciousness, especially in regards to race?

DW: I feel like the majority of our identity is grounded in our name and what we do. We introduce ourselves to people we meet for the first time by telling them our names. Unfortunately, we can’t always encounter someone in person, so in those instances we have to rely solely on our name and credentials. Oftentimes for black people, our names have prevented some of us from getting our foot in the door simply because of stereotypes. In turn, naming trends have been altered within the black community over various decades to become more race “neutral” and racially inconspicuous on paper. This adjustment bares a scary resemblance to the renaming of black slaves by their masters as a control tactic.

EC: When did you become interested in exploring issues of identity, particularly racial identity, in your work?

DW: During the third residency of my graduate program, I had an epiphany. I was making work dealing with women and body image and realized that I was hiding behind these topics. I could barely talk about the work during critiques. I had more to say and wanted to point some things out that were exclusive and controversial. So I told myself that I only get one chance to get this right. I decided to explore black culture and forged ahead.

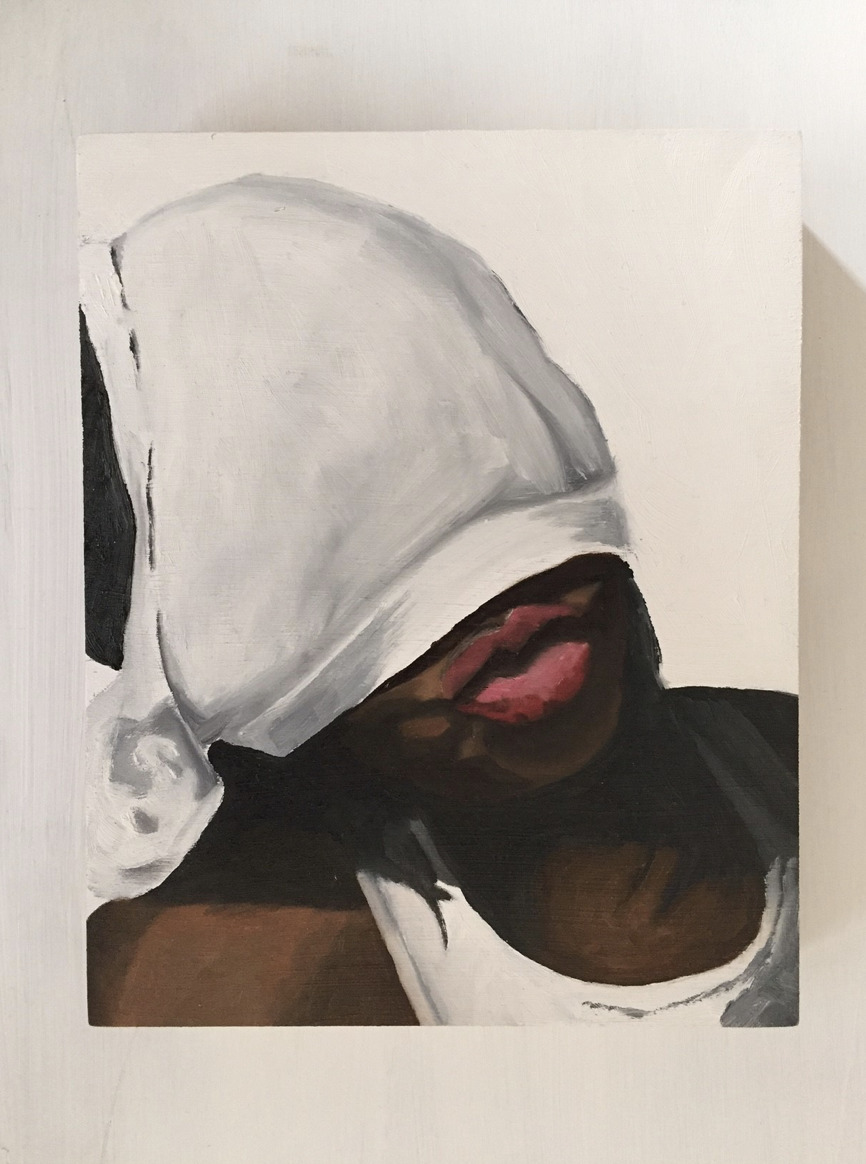

EC: The new series of women is different in several key ways. First, the eyes aren’t covered. Instead, women including yourself wear a red handkerchief. What’s the significance of this garment?

DW: Yes! It’s very different from the previous series. The red garment represents the idea of the “mammy.” I thought about Hattie McDaniel, who played Mammy in Gone with the Wind and won an Academy Award for the role in the 1940s. I wanted to tie the perception of that image in with the use of the garment today as a fashion statement.

EC: Also significantly, you decided to paint white women in “What’s In A Name?” I am one of them. Why did you bring white women into this series?

DW: Painting people who I am connected with in some real and genuine way is a part of my practice. I wanted to simply acknowledge two out of a number of white women who genuinely acknowledge the existence of systemic racism and who challenge white privilege through their words and deeds. It was important to me to go that route with this series.

EC: Gallery Luperca had announced a few months back that they would be looking for a new space because the building was sold. That date came sooner than expected. What was it like to hear that they were losing the space before your show and how did you feel about the result?

DW: It was not a huge issue at all for me to hear that news before the show. I’m very much a solution driven, get it done, bottom line type of girl and Sara Lederach and Katie Wolf of Gallery Luperca didn’t miss a beat. When they told me that they had an alternative space in the wake of having to vacate, I was good with it. I felt great about the result.

“What’s In A Name?” is on view at Fond Object until October 8 with a closing reception at 7-10pm.