My friend X and I walk into the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston’s glowing red main gallery. Inside, scant viewers wander around the plush carpeted tentatively, as if unsure where they’re supposed to go. Most of us perch obediently in front of a giant screen, where the focal point of the exhibition, Diane Severin Nguyen’s titular film IF REVOLUTION IS A SICKNESS is projected.

When we arrive, the film is midway through. As I settle in on my side of a long bench, beautiful teenagers dance to K-Pop and voiceover lyrics that belay vague collective defiance. Their bodies would inspire millions, the voice-over asserts. The teens are posing in front of Polish political statues, primed to begin their nation-building project through movement. Then they’re underneath an overpass or writhing in synch on the floor of what looks like a squat house, barely furnished, chilly in its lack of decor or creature comforts. The fashion and color scheme are mesmerizing—peak Gen Z in their allegiance to studded belts, crop tops, and baggy pants in matching hues of red and black.

The film’s narrative follows Weronika, a Vietnamese orphan who washes up on the shores of communist Poland and is taken in by a dance troupe of young revolutionaries—a political estrangement as much as it is an inclusion, and a nod to the sizeable Vietnamese diaspora in Poland, the twinning of Soviet thought between the two nations. As Weronika joins the group, she is initiated through a series of rituals. One includes smashing Weronika’s head, wrapped in a red bandana and matching silk globes, into a heart-shaped marshmallow that rests on a concrete floor, glass shattered around it. An unseen teen wearing lacy black gloves presses Weronika’s face further and further into the ruby red mess. The scene is beautiful, violent, and erotic, oozing with hyper femme and queer horror. Minutes later, the teenagers press a balloon of the numbers 1989—the year of the Tiananmen Square massacre, the Berlin wall fell, and Taylor Swift was born—in an act that could be drowning or baptism or both. “I don’t get it,” I whisper to X, “but I like it.”

Not getting it is part of the point, at least at first. Philosophy and metaphor weave underneath the surface of the work. It defies definition, bringing one back to the preverbal. This feels fitting given the work’s themes — migration, political dissent, the echoing of resistance movements and displacements. It reminds me of something that trauma expert Dr. Gabor Maté said about emotional triggering; sometimes you can remember something, but not recall it.

Can a pop song be a conspiracy? How can dance be an act of collusion? Nguyen’s original choreography and catchy lyrics set to a communist color palette draw you into the formula of a known world, that of one’s own youth nostalgia and righteousness, a hunger for good or justice, before we learned about the fractal nature of these concepts. Seeing young people in (literal) collective action, I can’t help but be reminded of my own radicalized youth and the collusive spaces that fostered it—in the back of dive bars, at Bay Area community meetings, thrashing the crowd of punk shows on sticky basement floors in downtown LA. We all remember times in which we were emboldened by being one with our peers, the feeling of having collective agency is intoxicating, if fleeting. Nguyen critiques this easy sense of belonging, equating it to sycophantic fandom, but in a way that holds reverence for fandom, that is both the self and outsider.

IF REVOLUTION IS A SICKNESS gives no easy answers to art and social activism. “I wanted to make something morally ambiguous,” Nguyen explains to me via phone. The exhibition and film take their name from a chapter of Saints of the Impossible: Bataille, Weil, And The Politics of the Sacred, a book that considers Christian mystic Simone Weil and philosopher George Bataille’s radically different perspectives on what self-transformation means in terms of revolution. “Does it mean being obsessed with death or obsessed with life?” Nguyen asks, synthesizing the premise of the book. For Nguyen, this question is related to the confusion of being an artist, and locating the ego within one’s desire for impact. The result is a film that feels political without telling you how or why.

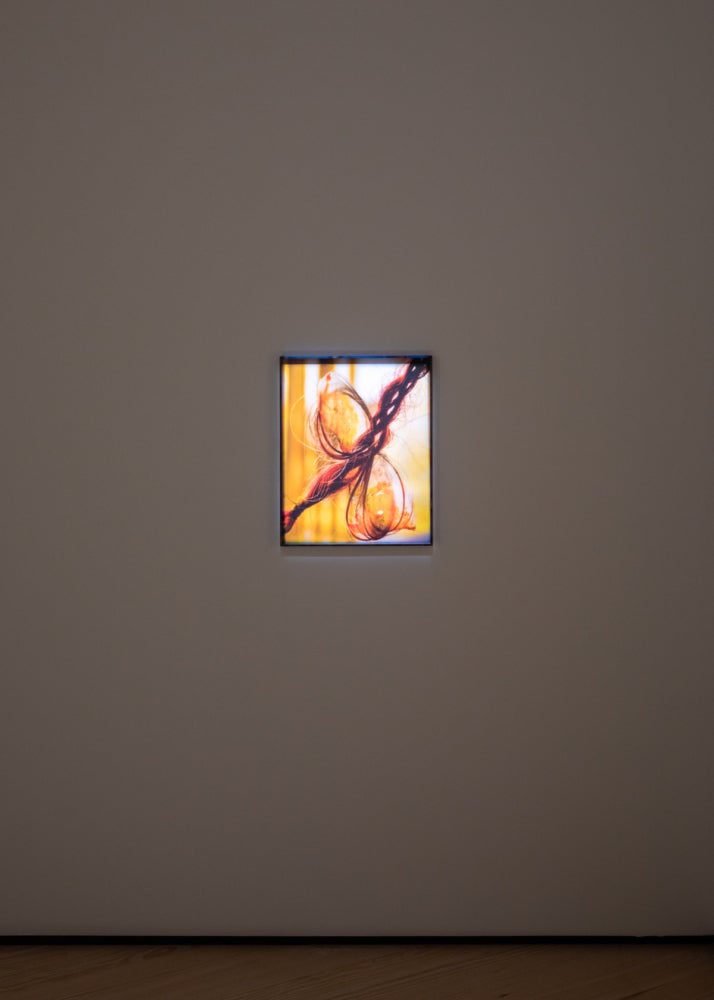

IF REVOLUTION IS A SICKNESS is crowned by a suite of moody photographs punctured by glimmers of light that reveal but do not quite illuminate the objects. Nguyen’s slimy sutured flesh (Kill This Love, 2021), pierced fruit rinds (Against the Sun, 2021) and membranes pulled apart by metal (Daily Affirmations, 2021) echo each other yet never quite betray their materiality. Nguyen describes her photographic process as searching for an aura, which leads her to truly understand what an image is. “What can I feel and not just know?” Nguyen asks of her objects. The exhibition also includes a site-specific billboard Not in this life (2023), which references the discrimination that Vietnamese fishermen experienced in the Galveston Bay in the 1970s and 80s.

Much like Nguyen’s photographs, IF REVOLUTION IS A SICKNESS is a monstrosity of personal obsession and theory. It combines Nguyen’s own K-Pop obsession during the pandemic with visual exercises in collectivity that tests the concept’s limitations. “K-Pop was really intellectually stimulating to me,” Nguyen tells me via phone. “There is something so photographic about it. These bodies were molded by the camera.” The film’s sonic field is peppered with political quotes ranging from Hannah Arendt to Mao Zedong. It’s a body of work that mines its hypocritical glitches, weaving them into its world-building until one can’t tell where the artifice begins and ends, how to pinpoint the critique and the sincerity. As Cat Zhang’s essay “ANTI-ROMANTICS,” the author equates Nguyen’s work to the current social media “Bimbo revival.” Like the self-aware hyper femmes of the internet, Nguyen’s gyrating, ardently socialist teens are “winkingly mocking [their] own zealous commitment to this tribe.”

In a recent interview with psychoanalyst and author Jamieson Webster, featured in the exhibition’s catalogue essay, Nguyen troubles her allergy to certainty, and the process of making a new body of photographic work—a medium so tied up with monolithic, colonial interpretations of knowledge—while witnessing the empathic “yes’s” of social movements in Hong Kong and New York. She speaks to being ideologically caught in the middle as an artist, wanting to keep a fidelity to uncertainty in her creative practice while also not adopting, as she puts it, “the same political position as a Nike ad.” IF REVOLUTION IS A SICKNESS asks the question, how dissimilar is fandom from political identity? What pleasures of belonging are nested within them, steeping one’s individual burdens under the camouflage of oneness? When Nguyen’s teens sing, the part of me that’s inside of you / it’s you absorbed inside of me, can we help but feel a little bit comforted by the prospect of being whole?

As X and I watch, I think of our position as diasporic femmes in a majority white PhD program, and the immense isolation and collusion of this fact. Hot blood and a red heart, the teens sing as they dance, Let’s join the workers and the peasants and march. “Literally everyone in our program,” I turn to X and snicker, tasting the bitterness in my own voice. We have spent hours at my kitchen table dissecting the performative labor politics of academia and their attendant micro-aggressions. We’ve sat across from one another unspooling the responsibilities of our mediums, art housed in the ivory tower, a place that never conceived of us in its construction, but a construction we benefit from nonetheless. In this scene, Nguyen plays into this dichotomy, winking at the impossibility of living up to these responsibilities yet dancing with them nonetheless. At the time of making the film, Nguyen questioned her own education. “Why do I have certain beliefs and who they apply to?” Nguyen wonders out loud when we speak.

In trying to unpack the ambiguous political **feeling** that Nguyen’s work gives me, critical race theory patron saint José Estéban Muñoz comes to mind. Muñoz would have loved K-Pop, or its potential anyway. He was a scholar of play and the ways in which the subaltern can use it to fuck with hegemony. In his posthumously published book The Sense of Brown, Muñoz argues for affect as a path towards political solidarity. “[A]ffect might be a better way to talk about the affiliations and identifications between racialized and ethnic groups than those available in standard stories of identity politics. What unites and consolidates oppositional groups is not simply the fact of identity but the way in which they perform affect, especially in relation to an official national affect.” Muñoz goes on to suggest that resistance should not be marked in terms of “simply being” but “through the more nuanced route of feeling.”

Revolution as sickness. Brown as feeling. Movement as collective action. Movement as belonging. Both Muñoz and Nguyen splinter the Cartesian divide between mind and body, politics and affect. Both assert that feeling is political, and often elides conscious understanding. I leave the gallery energized, both ready to write and ready to dance.

This essay is part of Burnaway’s series Conspiracy.

Read the other entry for Conspiracy – A Warning to Slow Down: In Conversation with Lauren Strohacker and Dr. Lisa Minerva Tolentino.