A red light races, doubles back, and moves swiftly along the edges of the corridors and stairways in the Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art exhibition Old Red, I Know Where Thou Dwellest. The installation, titled Leukos Lukos after the slippage between the Greek words for wolf and light, is the work of Lauren Strohacker and Dr. Lisa Minerva Tolentino. It lives on the periphery of transient spaces and is controlled by an algorithm that turns LED strips into flashes of color left in the wake of running animals in the woods.

Like Strohacker and Tolentino, I’m interested in how canids are experienced, represented, and imagined, and what that can tell us about being human. In my two-channel video Heavy Water, a biologist working for the Savannah River Site (Aiken, GA) delivers a lecture about wild dogs whose mythic relationship to the protected three-hundred square-mile nuclear weapon facility is embellished to justify its displacement of local residents, and obscure the violence sustained by its activities. The video’s two channels enact a confluence between two epic timelines: the deep history of the Carolina dogs, who some speculate descend from the continent’s first wolves, and the precarious future imperiled by nuclear weapons programs and the production of radioactive waste.

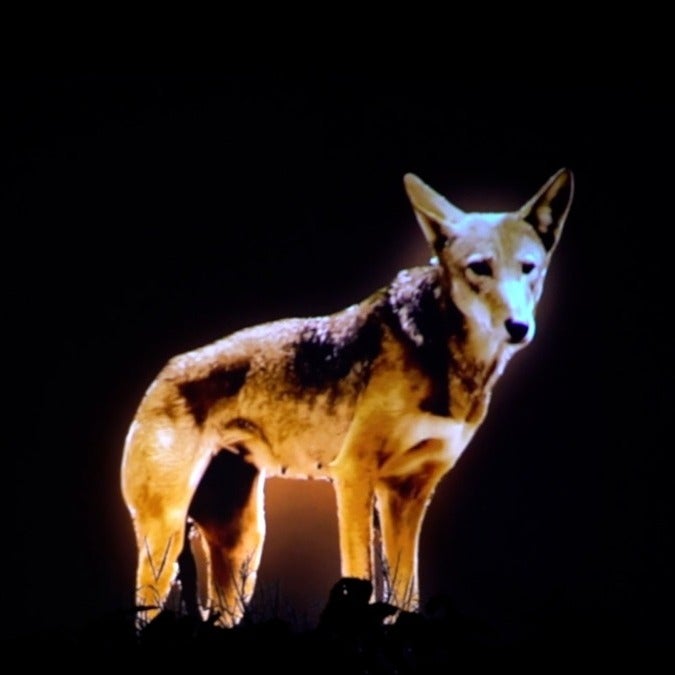

Leukos Lukos is one of three works in Strohacker’s solo exhibition that takes as its starting point the very real possibility that red wolves will become extinct in the wild for a second time. The last known group of wild individuals live in and around the Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge in eastern North Carolina, just four hours from SECCA.

Erin Johnson: What is the origin of this project and how did your collaboration begin?

Lauren Strohacker: In 2018, Wendy Earl, who was the curator at the Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art, wanted me to start thinking about a project for SECCA. So my first question was, what wildlife lives in North Carolina? And then of course, the red wolf caught my attention because I had learned that they’d already gone extinct in the wild once. And now there’s only, you know, a handful left in the wild.

Simultaneously, I started thinking about what I see in people’s houses, what people decorate with. And I started thinking about LED strips. And I thought, what if we made something that [laughs] didn’t look like a wolf? I started dematerializing the visual of the animal into an essence, the movement. And my thought was, well, what if we could code an LED strip to be the length of the red of a red wolf and move in ways that are unpredictable?

Lisa and I have known each other since 2013. We were colleagues at a private, independent school in Phoenix. And we remained friends and always knew we wanted to collaborate on something. I asked Lisa if this would be something she’d want to work on, if she thought it was feasible.

Lisa Tolentino: I told Lauren, “I’m not sure if I can do it yet.” My background is computer science, and I’ve been working with processing languages to create different types of generative media art for seven years. So I already knew how to use the Arduino platform and work with electronics. I had never programmed an animation on a physical light strip, so that was totally new for me. I needed to create code that would make something look like it’s alive. So I had to pull from different techniques to do that. And it really feels like I did more of an animation than anything else, just in a single dimension.

EJ: How did you land on this idea of translating an animal into light?

LS: I got in touch with the Wolf Conservation Center in New York. I spent a weekend there observing the red wolves, taking sound recordings, speaking with experts. I took my own videos, but I also shared the Wolf Conservation Center’s videos with Lisa. One of the big things we wanted to get across is that red wolves are very different from gray wolves. They’re different in size, they’re different in the size of their packs, they move erratically, and they’re very shy. They’re not as bold as gray wolves. Every once in a while, you get this whoosh of one running by, it was just this momentary thing, and you knew it was an adult red wolf. You’d barely see anything but a flash of red. And if they go extinct in the wild, I don’t want our memory of them to just be images of them. I wanted to make something where they could be felt.

LT: Yes, to use light to convey the loss of a being or to introduce its presence into a space. It’s not intrusive in the way that sound is.

The red is really the warning of loss, the warning of extinction, the warning of death. And a warning to slow down.

EJ: How did you determine the kinds of movement for the light?

LT: We didn’t want them [the lights] to seem stalking. We wanted them to seem unsure, ready to bolt at any moment. Pausing and lingering, and then maybe turning around, or going back the other way. Pacing and then walking and running. So, what I did to code these was basically create a probability table, where you have different states that the wolf could be in. And then based off that current state, you create a probability for a transition into a different state. If it’s in a pause state, there’s a 50% chance that it could go to the left based on the direction it was going previously. If it was heading left, it’s probably going to continue heading left. So then I would say, “Well, then there’s about a 60% chance it’s going to go that way. Or, there’s a 70% chance it’s going to go this way.” Then you link all of those states together. That’s how you get that kind of movement. The other thing that I had to contend with is that when you’re looking at a solid color moving back and forth, it looks like it’s getting bigger or smaller. I had to create an array—I would have to fade out the color towards the end. I also factored in doubling the speed or changing the rate at which the LEDs are changing to show that it’s running away versus walking. So it’s like all these little fine-tuned things make it feel more alive and breathing.

EJ: The work is installed in transitional spaces, spaces that connect spaces. The red light reminds me of stoplights, alarms, Jenny Holzer and Alfredo Jaar’s work. Do you see any connections there?

LT: We are in a space of transition, a choice as human beings. We have to decide—are red wolves only going to live in captivity again? We must do more. Red often signals what society has rejected in a way, danger, danger, danger. It’s a warning red. We need to pay attention to this. There’s a parallel between the sounds of coyotes and wolves and ambulance sirens; the sound makes us perk up, right? It gets our attention. That attention could lead people to places where they wouldn’t think that they could have an experience. So of course, these hallways and the staircase and now we’re moving them to places that are even more unexpected. They’re going to be work that you stumble upon. They’ll see a red light on a wall, and that might lead them up to it. It’s going to allow people to meander and wander in different ways.

LS: Yes, yes, the red is really the warning of loss, the warning of extinction, the warning of death. And a warning to slow down. One of the main causes of casualties of the wild red wolves and many animals is being hit by cars, very much literally people not slowing down and then taking these very rare lives away. So it’s fascinating to think about how red has all these translations, and it hopefully will spark engagement.

EJ: The show has three works: projections of wolves outside at night, a sound work outside, and then the light installation inside. And I was just thinking about this kind of the figurative versus the abstract. The figure of the wolves is in the context of the outdoors. And then inside, we’re with the light. Can you talk more about this?

LS: I knew from the beginning, whatever I put inside the museum had to be the most, for me, radical work I’ve ever done. I had to push myself to eliminate what I had thought before. Most people love looking animals, right? That’s why people buy a bunch of art with animals. Tourism with wildlife is huge. I wanted to push myself to resist that for this project, to not rely on our intrinsic interest in wildlife, visually.

An exhibition for me is practice. It’s a way to just say, hey, I’m trying this. My main goal is to get people to realize that red wolves exist, they’re in danger. We have to make a decision if we’re willing to let them go or if we’re willing to look at what would be needed to bring them back. The projections are the most accessible, almost like a step into the more abstract. The sound installation is literally a recording of wolves, and when you hear it disembodied like that, it’s become something else. Same with the light—once you go into the gallery, which is a highly controlled environment in so many ways—it’s almost like it’s even further abstracted. The wolf does not belong in the gallery. And so this is the best that we can do to bring them inside.

Karen Bradshaw is a lawyer from Arizona and recently wrote “Wildlife As Property Owners.” In the book, she argues for extending the legal right to own property to wildlife. I shared some of her writing on Twitter, and then she DM’d me. She had seen my work on the US-Mexico border wall, jaguar projections that I had done in 2017, in a USA Today documentary. She saw that, and said she reached out because the jaguar was the inspiration for her writing on wildlife as property owners. So we got connected that way, and then she sent me her book. I read it in two days. She’s such a great writer, so much clarity and vision of what she’s hoping to achieve long term. “Wildlife as Property Owners” was a big eye opener for me to also think about my practice in terms of my own backyard. What can we do with our homes? I think that probably led into the light intrusions [the light installation] too.

I think the other thing, if we’re really going beyond like art in my practice, I really enjoy good horror films. Being afraid lends itself to wildlife encounters. The history of folk horror is really fascinating to me. The land having its own life. I watch and analyze horror films from my own experiences with wildlife; I get afraid and then I think it’s this beautiful experience and it stays with me. Hopefully it stays with me for my whole life. I try to recreate those moments that are not just necessarily beautiful, but reactions to wildlife that are predators, or take you off guard. I think that’s a valuable thing that I try to think about in my work—how can I keep people and myself on edge?

Lauren Strohacker: Old Red, I Know Where Thou Dwellest is on view at Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art (SECCA), Winston-Salem, NC through August 27, 2023.

This essay is part of Burnaway’s series Conspiracy.

Read the other entry for Conspiracy – POP POLITICS: Diane Severin Nguyen’s IF REVOLUTION IS A SICKNESS.