The High Museum of Art’s recent exhibition is the institution’s first survey dedicated to Deana Lawson, providing viewers the chance to witness her work as a robust narrative rather than a static or singular image. This photographic retrospective, spanning over two decades, simultaneously confronts recent debates surrounding the artist’s works while also noting the objectification and abjection inflicted upon Black bodies throughout the colonial history of photography. The medium’s violence, which emerged at its inception alongside racial “scientific advancements” like eugenics, rendered Black men and women as racialized fodder—objects studied for the purpose of white advancement. The exhibition stresses the capacity for Lawson’s work to reimagine a nostalgic Black past severed from the bonds of this objectification. Furthermore, the show deliberately reminisces on pervious moments of love, desire, family, and intimacy.

The exhibition opens with reflections. The High boasts a dedicated space titled “Reflect and Expand,” showcasing a series of reviews of Lawson’s previous shows. This platform includes a billboard featuring onsite reviews from the museum’s public audience as well as statements from spectators, including thanks to the artists and expressions of love for the show. Ironically, the continuous remarks on the sensation of Black nostalgia make Lawson’s works inexplicable, as the artist attests to her photos consisting of either found images or highly staged productions. Some viewers include statements such as, “Authenticity. I see homes in which I grew up. I see emotions in which I felt…,” “I found myself remembering my childhood,” and “[These images] take you to a place of understanding a comfortability.” Detouring from the usual organizational structure that situates public reflections at the end of an exhibition, the retrospective’s design both informs and orients newcomers toward a specific expectation of the artist’s works particularly in its Black nostalgic perspective.

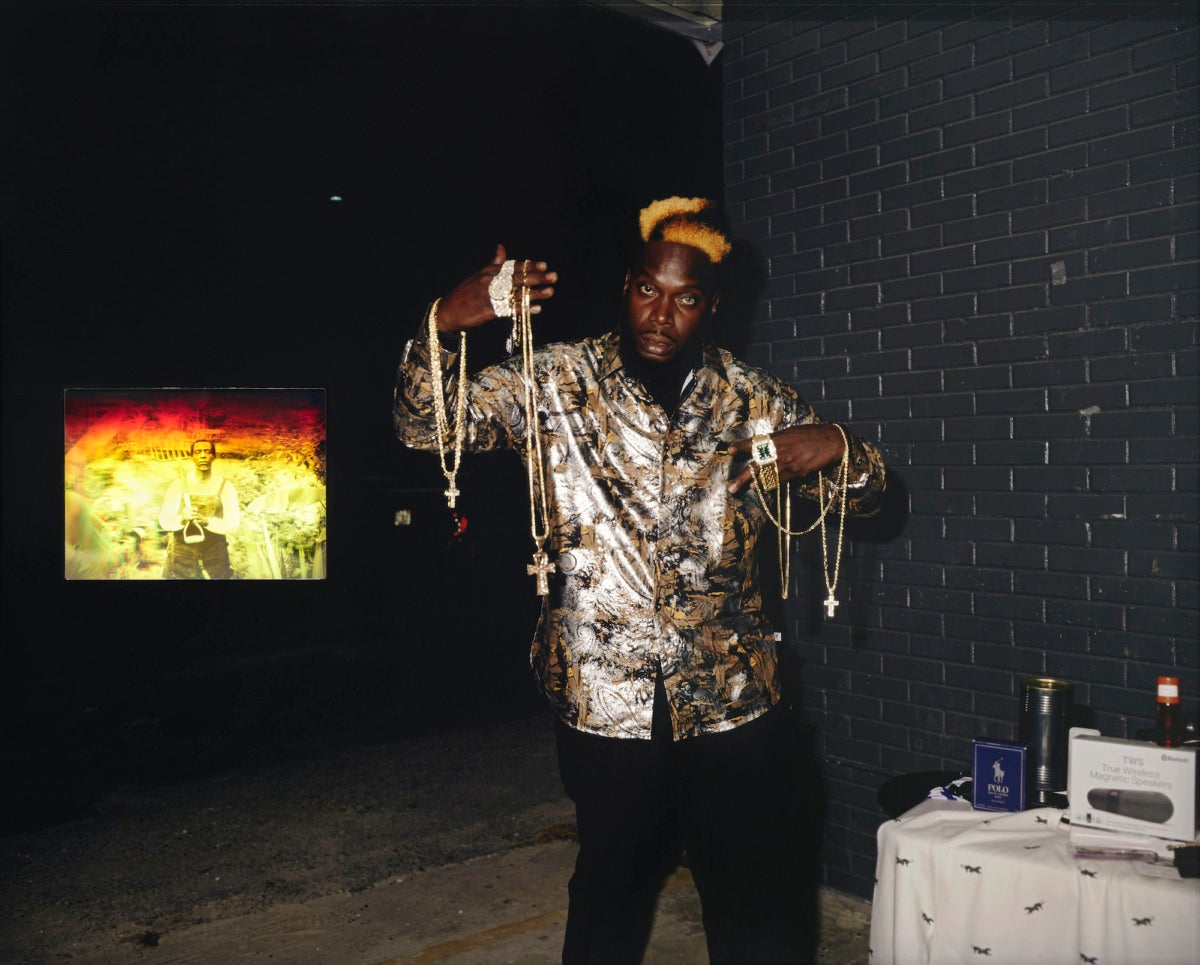

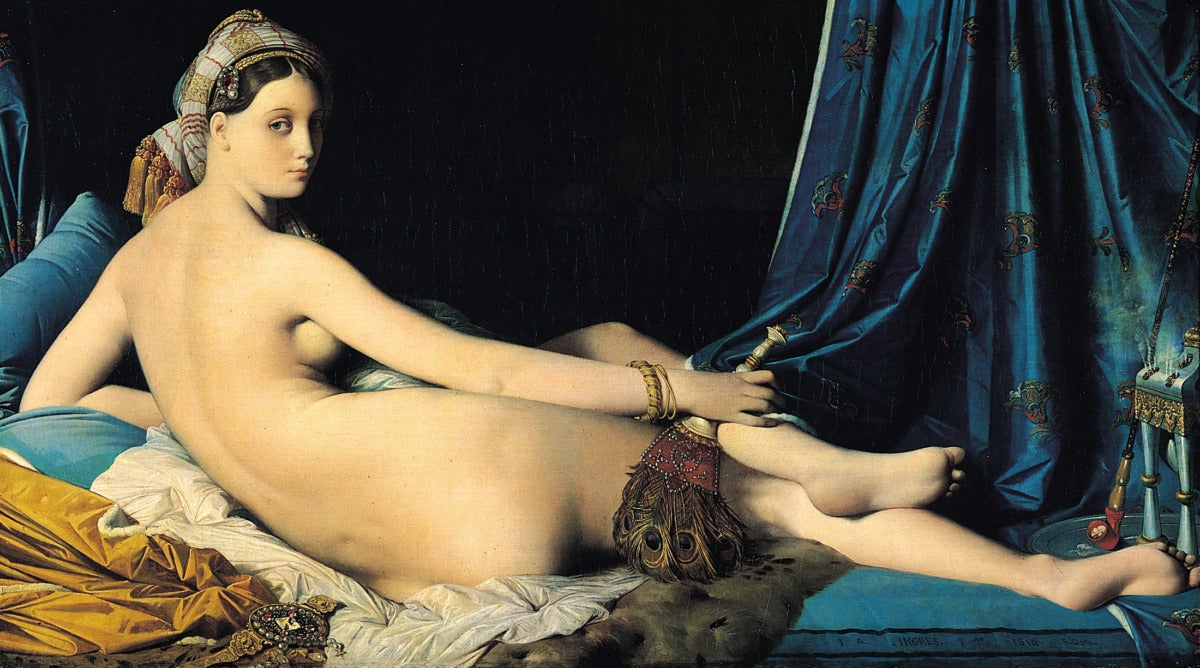

Upon exiting the reflection space, viewers encounter Lawson’s 2015 photograph Ashanti. A nude Black woman lounging on a cheap stripped bed in an ethereally sparse room. Her body’s positioning clearly references Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’ Grand Odalisque (1814). Placed directly beside and before the exhibition’s description, which refers to Lawson’s photos as “portals to imaginative realms…” and an “intervention to the camera’s long history of objectification and subjugation,” Ashanti’s nude body speaks not only for the first installation space but the entire exhibition. Utilizing both her location and historical representation, the model transcends into a universal symbology, her body standing in a liminality between a Black past and present, among sexual acceptance and refusal. The retrospective references a sentiment toward female sexual symbology continuously throughout the exhibition, featured in an array of found and staged photos devoted to expressions of the Black female form include 2 Live Crew Video Girl (2008), The Beginning (2008), Three Women (2013), and Nicole (2016).

The model transcends into a universal symbology, her body standing in a liminality between a Black past and present, among sexual acceptance and refusal.

Black women are not the sole focus of this survey, as an assemblage of Lawson’s works includes representations of Black masculinity, childhood, heritage, and family. Artworks like Wanda and Her Daughters (2009), Son of Cush (2016), and Baby Sleep (2009) feature Black mothers and fathers holding on to their children against the vulnerability produced by the cameras lens. With fixed, direct gazes toward the viewer, a private look inside the Black domestic space, and clothing befitting the traditional Black aesthetic, the Black family is seemingly laid bare in Deana Lawson’s work. Confronting a historically contentious topic of discourse—through government documents like the 1965 Moynihan report and racist political trouping, as with the Reagan-defined “Welfare Queen”—Lawson incorporates the Black family as an entry to self-reflecting provocation. Coulson Family (2008) exemplifies this practice with its tableau reminiscent of an intimate family photo that toes the line between production and documentary. Yet, one of Lawson’s newer works Cloud Assemblage (2020) pushes this boundary of familial intimacy further. A collection of gathered images ranges between lost personal heritage and infamous moments of time, such as a local class photo juxtaposed with a captured moment between director Steven Spielberg and actress Whoopi Goldberg on the set of The Color Purple. Liminal space glue such imageries together.

The High also links a series of photographs referencing both heritage and the passage of time, highlighting Deana Lawson’s preservationist inclinations. Works such as Cowboys (2014), Kingdom Come (2015), and The Garden (2015) reimagine a mythical Black past utilizing historical references, cultural ceremonials, and nature as backdrops to these dramatized images. While Deana Lawson’s photographs are contemporary in objectivity, the artist’s ability to reframe relinquishes time as an atypical space, molding together both ancient and contemporary Black motifs. In the photo series Mohawk Correctional Facility (2012-2014)—one of the few photographs featuring the artist’s personal family—temporal maneuvering comes into focus. This sequence features a two-year long strand of personal correction portraits, demonstrating both the physical and metaphysical passage of time. Once again, the photographer divulges the particularities of Black existence, regardless of its unsightly presence.

Deana Lawson’s thematic on Black sexuality, family, intimacy, and heritage culminates into a reflection. The final images in the exhibition feature mirrored frames. Photos such as Chief (2019), Holy Miami (2021), Axis (2018) and Black Gold (‘Earth turns to gold in the hands of the wise’) (2021) allow viewers to literally see themselves in the work, affixing the viewer’s reality to the produced photo. As I walk away from this exhibition, I must say that I refuse this binding. Am I—or my mother, sister, aunt—any of these women? Is my brother, father, friend, or partner any of these men? No. I can definitively say that these photos do not show my personal experience as a Black person. Yet, I cannot deny feeling the previously reported sensations of nostalgia. There is a tension here: between the obvious display of critical praise at the beginning of the exhibition and scholarly critiques of the artist’s work; between the Black past and the present; between hypervisibility and respectability politics; and between my own refusal to consider any familiarity with these images and my visceral reaction of reminiscence. I remain at this axis, continuing to examine Deana Lawson’s semblance of authenticity.