Home-made, home-made! But aren’t we all?

I felt a deep affection for

the smallest of my island industries.

No, not exactly, since the smallest was

a miserable philosophy

-Elizabeth Bishop, “Crusoe in England”

Crafting America is a big show filled with over a hundred wide-ranging hand-made objects—from pottery, quilts and furniture to jewelry, garments and sculpture. The entrance gallery asks in bold letters, “What is craft?” and diffusely defines it as being “as simple or complex as you want to make it. In its essence, craft is skilled making on a human scale.” As one of its co-curators explained to me, the exhibition was arranged to let the work speak for itself. Meaning, don’t dwell too much on the fine print; let the visual cues guide the show’s message. This spirit, they elaborated, is best exemplified by the first two works one encounters: a silver tea pot so expertly made by John Prip (1958) as to appear machine-fabricated, situated next to a teapot that appears to be melting, made a generation later by Myra Mimlitsch-Gray (2005) using the same technique as Prip of hand-raising sheet metal. I must admit that the sense of this pairing isn’t as clear to me as it should be (I’m also unfamiliar with the process of hand-raising metal), but the show’s overall organizational structure is: four writ-large sections—“Declarations of Independence,” “Life,” “Liberty” and “The Pursuit of Happiness”—housed within galleries whose walls are painted shades of red, white and blue.

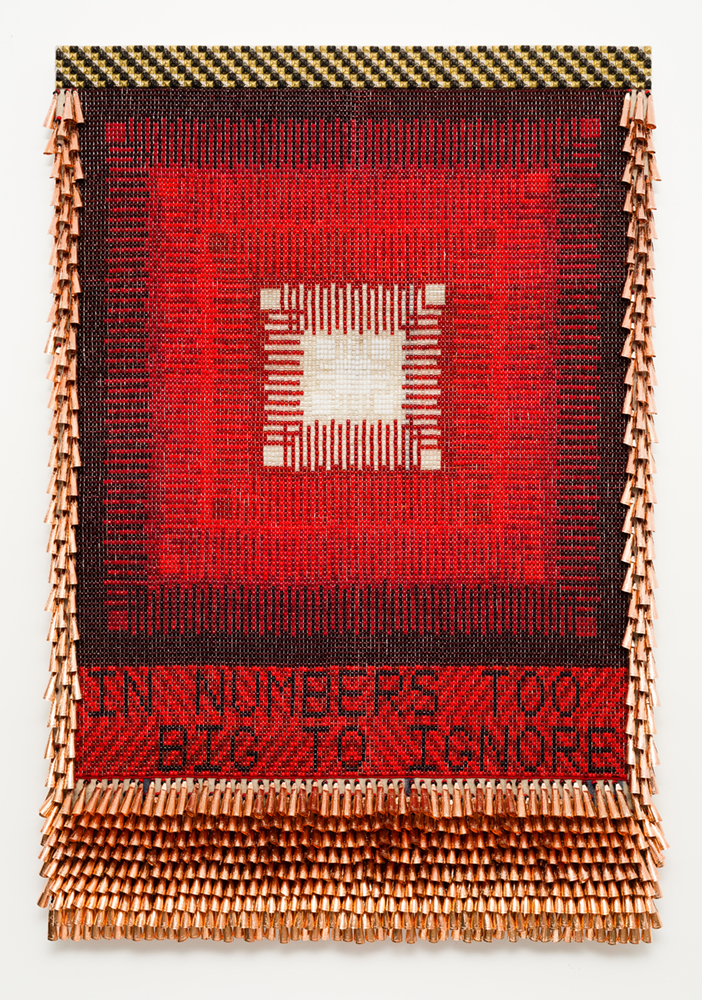

Before getting into that aspect, I want to point out a few of the exhibition’s many exquisite pieces: Jeffrey Gibson’s complexly woven, jingle-embellished tapestry, “In Numbers Too Big to Ignore” (2016); an orb-shaped traditional Acoma Pueblo pot by Grace Chino, bearing a bewilderingly precise geometric pattern; a wood chest of drawers meticulously fashioned out of packing crates and brushwood scraps by Gentaro Kenneth Hikogawa, made while the artist was incarcerated in a Japanese internment camp during World War II; one of Ruth Asawa’s ingenious looped-wire forms-within-forms; and one of Darryl Montana’s feathered, beaded and sequined Mardi Gras suits.

There are also just as many works on view that feel less dimensional—such as Flora C. Mace and Joey Kirkpatrick’s oversized bowl of glass fruit, Marilyn Levine’s trompe l’oeuil woodcarving of a jacket on a hook, or Prince’s iconic “white cloud” electric guitar, which was custom-made by David Rusan. While spirited and admirably executed, these pieces give the show a mixed-bag feel similar to its make-it-what-you-wish premise. You get the message: the field of craft in the US is large, contradictory and contains multitudes, just like the ongoing project of American identity itself.

But not so much. Here’s where we get to the show’s organizational structure: if indeed viewers are to privilege the show’s “self-evident” visual cues, the objects in the exhibition become subsumed by its overall thematic design premised on American nationhood as represented by the constituent elements of the flag and founding ideals. To extend the craft analogy, big tent nationalism is large enough to make room for those who wish to “make America great again” but not those for whom “America was never America to me,” as Langston Hughes wrote in 1936.

While some works feel fundamentally altered by this conceptual freight, others seem reaffirmed by it. What does it mean to have Jeffrey Gibson’s textile, which quotes Helen Reddy’s 1971 feminist anthem, function as an annotation of “Declarations of Independence?” And was Myra Mimlitsch-Gray’s silver sculpture meant to suggest an assimilationist “melting pot” metaphor? Does making “Old Glory” browner, queerer and more Indigenous constitute an adequate expression of America’s capacity for self-crafting—and if so, for whom? The exhibit conscripts its constituent art and artists to an already defined nationalist project rather than allowing them to function outside of it or define it for themselves.

Consuelo Jimenez Underwood’s “Home of the Brave,” 2013, serves as the exhibition’s emblem, in a sense—appearing on the cover of the show’s catalogue and in its advertising campaign. A US flag-like red, white and blue textile titled after a line of the “Star Spangled Banner,” the piece, according to the artwork’s label, was made using a rag rug technique that’s fringed with “native weaving,” its loosely deconstructed form held together with safety pins. Appearing within the “Declarations of Independence” section, the work does indeed embody many of the show’s concepts: of craft as a hybrid genre composed of numerous cultural traditions and skillful uses of commonly sourced materials; and an allegiance, albeit wearied, to an American identity worth mending and reconfiguring, wherein critique is embedded within a kind of faith in national symbology. The piece is a sympathetic echo of the show’s conceit and remains legible as such within its presentation strategy as it likely would without it.

A less patriotically encumbered version of the exhibition is intimated by the fine print of the show’s didactics and accompanying catalogue, which convey more nuanced explication and research about the histories and processes of craft itself. Another glimpse at an alternative exhibition configuration can be seen via a few works placed beyond the confines of the special exhibition galleries, in conversation with the museum’s permanent collection. A suite of eleven glazed stoneware and porcelain sculptures by Toshiko Takaezu is situated between paintings by female Abstract Expressionists such as Grace Hartigan and Joan Mitchell. The affect is transportive—aligning Takaezu’s singular forms and expressive glazing techniques with those of her art historical peers. It’s a moment that does so much work, bridging an art practice relegated to “craft” with a “fine art” tradition, in the process liberating and complicating the pieces themselves by their proximity with one another.

Crystal Bridges, while now in its tenth year of operation, is still in the process of defining itself as both a serious art institution situated outside of the coasts, and as an entity independent of its corporate and family founders. An exhibition such as 2018’s Art for a New Understanding: Native Voices, 1950 to Now was a precedent-setting survey of contemporary Indigenous art that sensitively challenged the settler-colonial and nationalist frameworks that accompany traditional definitions of “American” art and, in doing so, positioned Crystal Bridges as a thought leader. That show, which was accompanied by the adaptation of an institutional land acknowledgement, made a mission of carefully problematizing territorial assignments, especially for persons and communities who identify themselves beyond the boundaries of American citizenship, by allowing artists and artworks to express their own alliances. Needless to say, the exhibition would not have fit comfortably within US flag-themed walls.

Which makes Crafting America feel like a step backward, not merely in how it prescribes “American-ness” but how it echoes the red, white, and blue brand identity that defined Walmart during its critical growth period in the 1990s. That branding was ingenious in identifying Walmart as a “hometown retailer” aligned with “traditional American values” to the under-served rural Heartland that first composed its consumer base—an aesthetic strategy derivative of the American regionalist and landscape art of the museum’s foundational collection. In recasting those motifs, Crafting America risks feeling like an effort to align the museum not only with craft as a populist genre—supplies for which can be bought at Walmart—but a consumer one in which a notion of a diversified America can still appeal to Walmart shoppers. While the corporation has rebranded, dropping its stars and stripes in time with its ascendancy to global retail dominance (someone at the top understands Americana’s diminishing returns), its domestic identity still circulates in a regional feedback loop.

While it was impressive to see Sonya Clark’s “Beaded Prayers Project,” (1999–present) fill an entire room of Crafting America, it would have been more powerful to include some of Clark’s more incisive and direct critiques of US ideology, such as “Unraveling” (2015) in which the Confederate flag is dismantled, thread by thread, by hand by willing participants. This project reveals the difficulty of deconstructing such emblematic creations, and how short-sighted it is, particularly at this point in time, to see nationalist symbology of any kind as benign. Public refusals of the pledge of allegiance and national anthem on the grounds of their exclusionary promises are long since de rigueur among activists. Donald Trump and his far-Right supporters, in response, have deemed such actions “un-American” and firmly claimed the US flag and all its iterations as explicitly anti-progressive emblems. The most cursory reflection on the protest aesthetics of this historic, paradigm-shifting past year serves as a similar testament: while the January 6 white supremacist insurrection at the Capitol was a carnivalesque Walpurgisnacht of stars, stripes and bars, Black Lives Matter protests appeared to be largely US flag devoid.

Maybe craft in the US is like a picnic table I drove past recently. It was propped on its side in the center of a neatly trimmed lawn, its horizontal wood planks hand-painted red, white and blue, a “Proud American” sign leaning against it, alongside another: “Trump Pence 2020.” But if this is true, then craft is also the thousands of people across the country who have recently flooded the streets—in cities and small towns alike, in a movement born in the Heartland—waving new flags and signs of their own making, raging against the violences of the state apparatus, imagining new and more equitable forms of solidarity. America itself may be synonymous with craft only in the sense that it’s a fabrication. A yarn. A map and territory as false as Betsy Ross.

Crafting America is on view through May 31, 2021 at Crystal Bridges Museum of Art in Bentonville, AR.