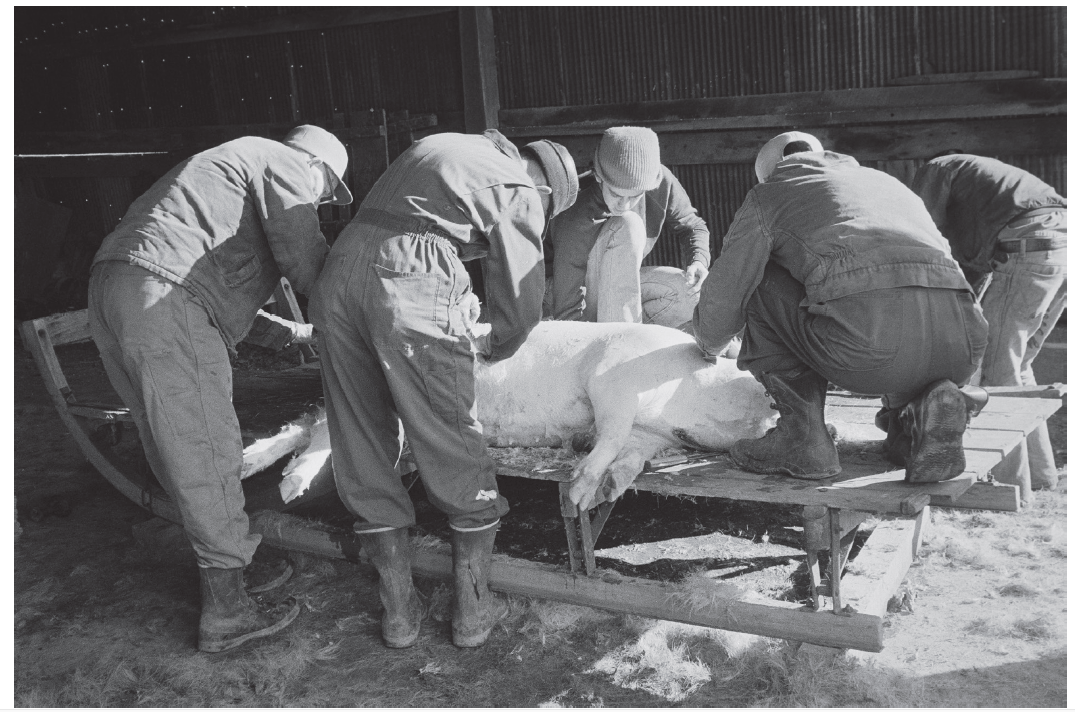

In Tanya Amyx Berry’s photographic series For the Hog Killing, I see a group of neighbors acting in a way that seems governed, like ballet, by a set of virtues. I see this in the way the hog is split down the middle and taken into pieces, like a series of choreographed movements, falls and follows. As when I watch ballet, the instructions are not known to me, but I can tell they are derived from ideals of balance, energy, or grace. The central splitting of the hog’s body visually echoes the symmetry of the body of a dancer—a little lower on the left arm, tuck your hips beneath your belly button. I can tell the workers are receiving instruction. There is almost always a group of people or a single person standing by—commenting, if I know a single thing about people.

In the photograph Loyce, I see a person bending over a tub, swiping the outside of it with their hand. I see their bent posture, which is the first position of the day. Ben Aguilar—the editor of the photobook For the Hog Killing, 1979—writes of the photo, “Loyce Flood (whose farm was the host for the annual hog killing depicted, and whose husband Owen had passed a couple of years before these photographs were taken) washes the outside of the galvanized tub that would be used for seasoning and mixing sausage for preservation. You wouldn’t need to do this, as the outside of the tub would never be in contact with its contents, but Wendell talks about cleanliness as one of the primary orders of the day, and Tanya has called this ‘doing the whole job’.” Loyce is a photo of preparation: the body of the hog isn’t present in it. The presence of the hogs makes me feel conflicted as a writer. Because these people are turning flesh to meat, I feel that I might be taking part in some cruelty. Cruelty asks spectators to intervene, and as a spectator with a voice, I feel urgency and tension—so I come bursting back into 1979.

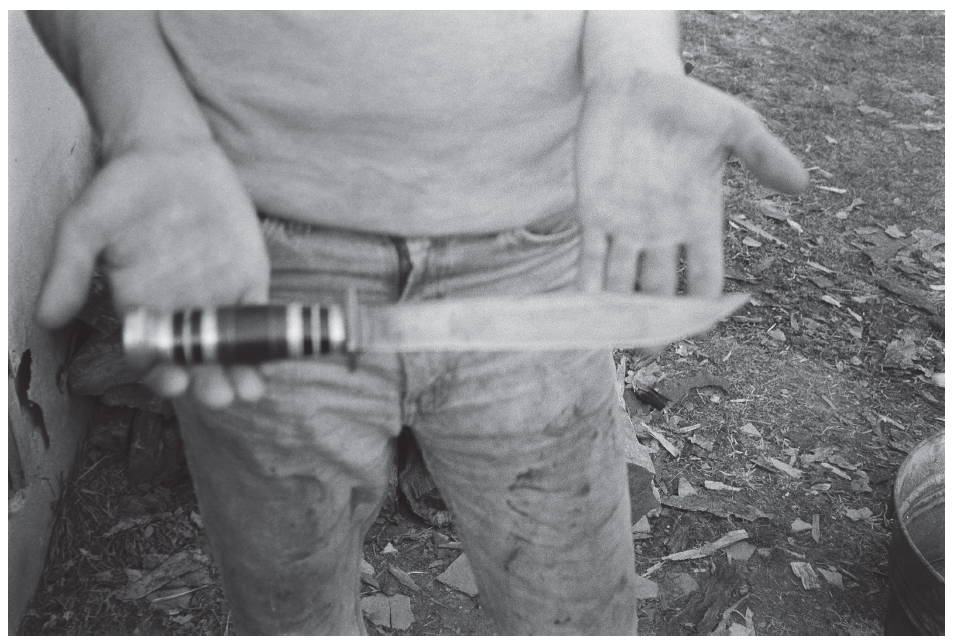

In Knife, I see a man holding out his hands with a long knife blade laid across them. I am worried for the tip of his middle finger on his left hand, under the knife’s blade; it looks like the end of a sausage that you cut off and discard. I am worried for his palms which look white and firm, as though they would have a good resistance to the knife. The knife threatens all flesh as meat in my mind, because I am just watching. The knife crosses over the zipper of his blue jeans, and I am thinking about how blue jeans are an industrial invention, how killing hogs this way is threatened by industrial agriculture, and how industrial agriculture catches speechless flesh in its zipper.

I went to Henry County, where the hog killing took place. In the afternoon I drove my car to the interstate on-ramp. The striped shadows of fences fell onto the grass slopes meeting the road. I felt I was travelling the ribbon hem of a blanket with my hand. Henry County was resting under it, creating its contours and turning its stories into dreams that I could not access. In Tanya’s photographs, I also see these slat fences. In the beginning, in late November, it is overcast or early morning. I know this because the fence isn’t stretched into shadow. Meb, an older member of the group, walks into the lot and singles out a hog. He walks him against the fence. In Careful Marksman, the hog looks wobbly and soft. The only shadows on the hog fall on its ears, its underbelly, a spot on its side. Meb looks down the barrel of his gun. He is a completely dark figure but for the curve behind his ear and the back of his hand. Behind the hog and fence is an open hillside. The tree line begins at the crest, singing: Oh, wouldn’t you rather?

This is the first image that stirs urgency and objection in me. The second is Hogs, a photograph of a hog looking through a wooden fence. His eyes are sunken looking, but his face is pictured dead on, so I think Tanya caught his gaze in the viewfinder. There are two severed hogs’ heads hooked by the snouts and tied to the fence. I want to know if the hogs know. The way the hogs’ heads are hung just the same shows that the work has propriety to it. But the living hog reaches through the fence and moves my jar of propriety aside so he can look in my eyes. I know that, when shooting a hog, it is necessary to wait for it to look in your eyes in order to place a bullet directly into its brain. The shooter is dependent on the perception and volition of the hog. I know Meb, the senior member of the group, was chosen for his accuracy.

I eat. I am a consumer, and I do not understand how I am alive. Because those killing the hog do, I enter into a trial of deference. I do not think Tanya misses the impossibility of the hogs’ gaze, the importance of their being alive, because she shows meat alongside the animals in Hogs. In Hams, Bellies, and Ribs on the Wagon, she shows a person’s hand next to the hoof of a partitioned hog, so I think she sees both hogs and humans as bodies. Everyone is aware of the hogs’ aliveness. Meb is using all his experience and focus to make sure they do not suffer. The people here know, and I am in the movie theater parking lot after seeing Charlotte’s Web. To encounter these photographs and this landscape is to layer wool blanket over wool blanket on top of my reflexive moral judgement.

I cannot do the work the Berrys do, but I will name some of the reasons I know the hog killing took place. Hogs allow for a diverse farm—they can make do with a wooded area, allowing the farmer to keep trees and sustain a farm. Keeping livestock is one of the few forms of perennial agriculture. Animal manure is one of the best ways to build soil. The destruction of small farms and replacement of them with industrial agriculture—whose only rule is profit unless the government intervenes—make most consumers dependent on an incredibly cruel system that is accountable to almost no-one. Factory farms are certainly not accountable to their workers, who are placed in positions where they are not allowed to pursue their own methods or make their own judgements, as the participants in the photographed hog killing did.

In her short story “The Dialectic,” Zadie Smith portrays a person who, eating a chicken wing, worries about eating meat while vacationing with her family, almost as in a day dream. The story’s first line is: “’I would like to be on good terms with all animals,’ remarked the woman, to her daughter.” And the story concludes:

As her daughter applied what looked like cooking oil to the taut skin of her tummy, the woman discreetly placed her chicken wing in the sand before quickly, furtively, kicking more sand over it, as if it were a turd she wished buried. And the little chicks, hundreds of thousands of them, perhaps millions, pass down an assembly line, every day of the week, and chicken sexers turn them over, and sweep the males into huge grinding vats where they are minced alive.

In an essay accompanying the photobook For the Hog Killing, 1979, Wendell Berry—husband of Tanya Berry—writes about his agrarian mentor Owen Flood, on whose farm the hog killing took place. Berry describes Flood preparing for a hog killing: “He would be pretty tightly wound, the form and cadence of the whole day to come fretting his mind. To nobody in particular, as if thinking aloud, he would say, ‘If there’s anything I can’t stand, it’s a damned nasty hog killing.’” Owen’s worry over and insistence on good work, which resulted in his tense presence, is radically different from the posture industrial agriculture asks of its dependents, which is to look away while consuming.

Many of the neighbors and friends pictured in For the Hog Killing also gathered on Owen Flood’s farm to harvest tobacco, a process that was photographed in 1973. In Tobacco Harvest: An Elegy, Wendell Berry writes, “The place, the work, and the people are mirrored in these pictures as they were. We look at them now with a sort of wonder, and with some regret, realizing that while our work was going on, powerful forces were at play that would change the scene and make ‘history’ of those lived days, which were enriched for us then by their resemblance to earlier days and to days that presumably were to follow.”

In the capstone image For the Hog Killing, the people look quiet and together. The sun is on their hats, and they are shoulder to shoulder. Many of the neighbors pictured here have since died, and it is neighborly help that allows self-sustenance to be viable and beautiful. The confluence of softness and violence in the image creates a wavering sound of the preciousness of life. I witnessed life in Tanya’s photos. After looking at them, I stood in my backyard, and I tried to take my stand, to press into the ground made conspiratorially by the people who lived on this land before me, by lead paint, dead leaves, earthworms.

Tanya Amyx Berry’s For the Hog Killing, 1979 was on view at the Pam Miler Downton Arts Center in Lexington, Kentucky, earlier this year. The photobook For the Hog Killing, 1979 is available from the University Press of Kentucky.