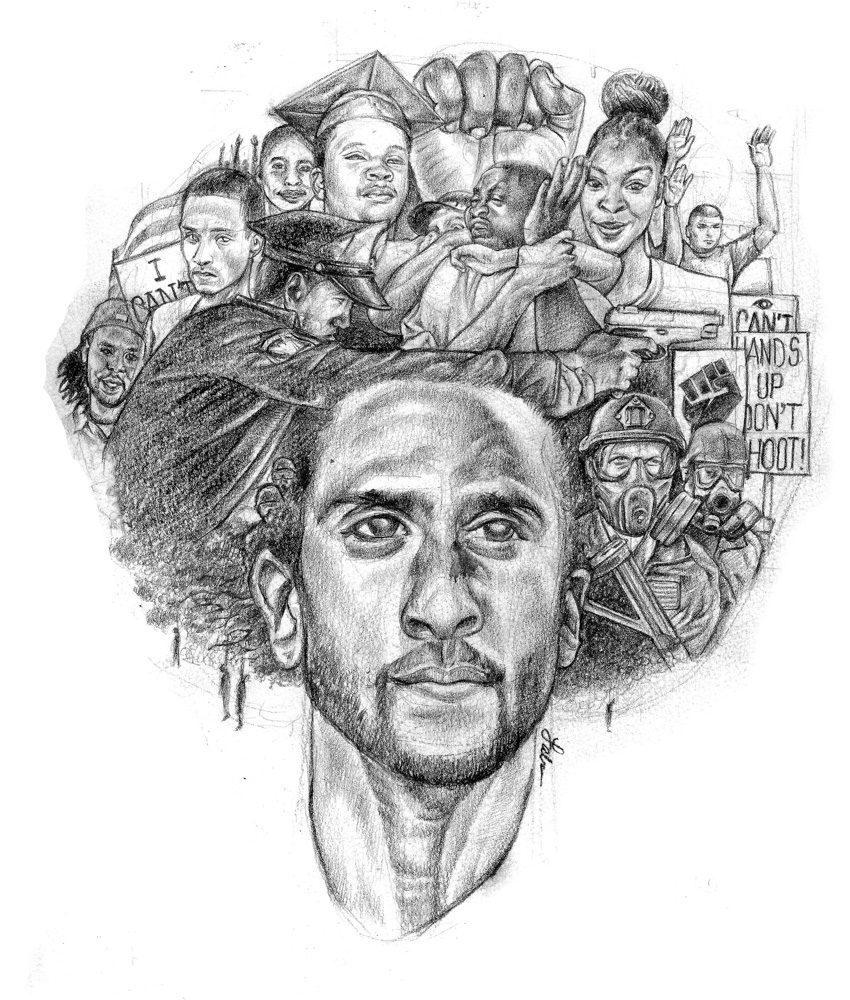

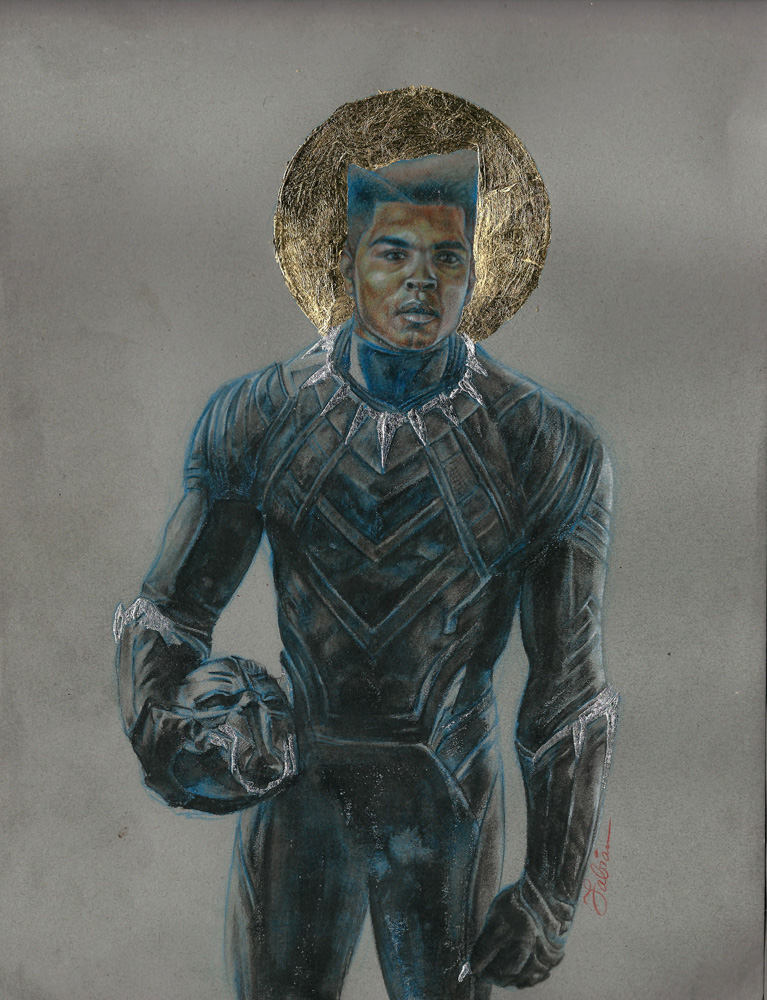

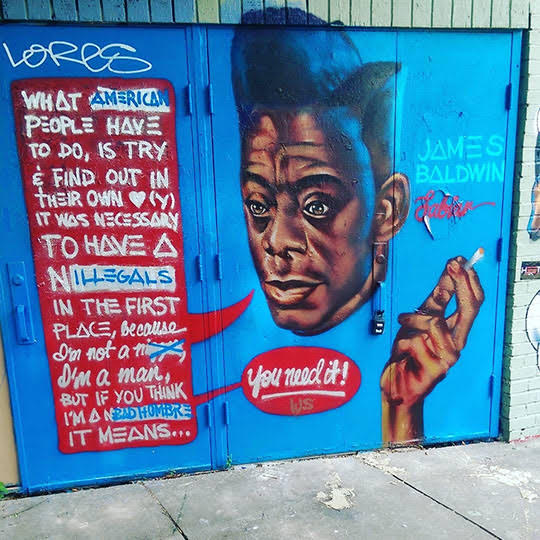

The record-breaking opening of Marvel Studios’ Black Panther last weekend is the perfect backdrop for this studio visit with Fabian Williams. The Atlanta artist took his game up a notch this past summer with his Civil Rights Superhero murals, including a mural of Muhammad Ali as Black Panther. Think X-men meets James Baldwin, Martin Luther King and Malcolm X. Then there’s his recent mural of a different sort of hero: Colin Kaepernick in an Atlanta Falcons jersey. Williams has received national media attention from the Los Angeles Times, Playboy and a host of Atlanta outlets. Creative Loafing named him Atlanta’s best muralist un 2017 and his Hosea Williams mural the best mural of the year. Last month ArtsATL awarded Williams a Luminary Award for leading a group of street artists who successfully challenged the City of Atlanta’s public art ordinance restricting murals in public spaces.

His exhibition of paintings, “Black History Repeats Itself,” opens on Saturday, February 24, at Future Gallery. I thought it would be fun to see what makes this brother tick.

Carl Rojas: How did you get into art?

Fabian Williams: I was always into art. I was kind of born that way. [Laughs] If they took my brain out and cut into slices, there’d probably be some art shit in there. Like, this guy is definitely stricken.

CR: So, what was your art like when your were a kid?

FW: Pretty conservative. My parents were super religious —well, my mother was. I was raised by my stepfather. My real father showed up later. So, I ended up being exposed to different ideologies. My dad is agnostic. He was in the military. Intelligence. He has a very analytical way of thinking. My stepfather was really regimented and disciplined, and that’s how they raised me and my brother. So I have this religious thing, then not religious. My artwork is my religion now, know what I mean?

CR: So, was your early art religious?

FW: Nah, not at all, dragons and robots and shit like that.

CR: You’ve been doing a lot of murals of late. How did you get into being a muralist?

FW: Peter Ferrari invited me to do a wall for Forward Warrior. I was like, uh, sure. I just took to it after the first one that I did. I liked how fast it moved. I love what the wall texture brought and what that spoke to. It’s the topic. It’s a lot of things that I unpacked. Learning how to use aerosol [paint] was a big thing for me.

CR: Do you like working on a big scale?

FW: I do like working big. It makes me feel like I’m in ancient times. All the masters worked real big. My favorite art period was the Renaissance. I like the way they did big murals in churches. I want to do a building like that and have my own sort of Sistine Chapel. That might end up being what my final joint is going to be one day.

CR: The mural you did of Hosea Williams over off Edgewood, is that the biggest mural you have ever done?

FW: Yes.

CR: How tall is that?

FW: About five stories. Sixty feet. It doesn’t look that big from the street. There were times when I was working on it and I’m like damn! I’m up here! You kind of have to turn on the other side of your brain to get that shit done because I am NOT a heights person.

CR: So it must have been nice doing the murals off of Wylie Street [with Forward Warrior].

FW: Oh yeah. Vacation.

CR: You’ve been painting Civil Rights Superheroes (Civil Rights icons with an X-men treatment). Who have you done so far?

FW: James Baldwin. James Francone. Martin Luther King, Jr. Malcolm X. Hosea Williams. Coretta Scott King. Harriet Tubman, I haven’t figured out where she fits in my X-men concept, but she’s going to be in that.

CR: Who’s next? What’s next?

FW: There’s a lot. I want to do an X-men’s origin with Frederick Douglass. He’s like Beast. I’m trying to think of who would be Wolverine.

CR: I took a fresh interest in your art when I saw those murals this summer.

FW: I’m going to show you the sketches. A lot of it I get just from messing around with my sketchbook. I make an effort to do at least 30 minutes for a sketch. Sometimes it turn into three hours,or a whole day even. But the goal was to have 30 days of sketches. That turned into like 90. Those sketches are what have I have based the subject matter of my murals and paintings on. They’re my roadmap.

CR: Makes total sense. Some people work from photos. Some work from drawings. Some work from nothing. There’s always different sources of inspiration.

FW: I’ve never been really good at keeping up with the daily sketching. This was the first time. They are usually just all around the house. Sometimes you just have to build up the guts and tell yourself I’m going to do this. Like, you see that pyramid right there [pointing]? That’s a mockup of the first pyramid. See how it isn’t at the same angle as the Dungeon Family pyramid, which is based off of the dimensions of the Great Pyramid of Giza. I didn’t know anything about architecture when I started it, and I had to eventually go and find someone that knew what they were talking about and what I was trying to do. That’s where a lot of this — of everything, came together. But I had to do it on my own at first, like many projects I start. I’ll play around with things and work on it by myself before I go to somebody else. And if I can figure it out myself, I’ll do it myself.

CR: You’ve had some national media coverage recently. How did the L.A. Times find you?

FW: One of my friends had contacted me when they reached out to her to do a news story about black people reacting to Barack Obama’s presidency. I guess she mentioned that I was an artist and she talked about my work and the nature of it and they then went and looked me up. They liked the stuff I’d been doing and they thought it worked with the story, so they hooked me up. And then I had a phone interview for about 30 minutes. Then they said, “We’ve got to come and see you.” They came and shot me and were asking questions for a total of three days. I didn’t know what it was gonna be, but it was the front page and everything. After that, other agencies started picking me up.

CR: Is that how the Playboy thing came about? After the L.A. Times?

FW: I think that they did see the interview, but the reason they picked up the story was the same as the L.A. Times. Once they started looking at my artwork, they liked it. The thing they respond to is the content of the art, and specifically content that is happening right now. You know, we are living in a historical time. All this shit that is happening with the government and Trump — this shit ain’t normal. Artists are an arm of journalism that is speaking about the situation. You need not the just facts but how it feels, what the deeper context is to what’s happening. That’s what I’m doing and the media responds to it. It’s not rocket science. You know, I went through this period where I was like, “How is this [media attention] happening?” Not that I wasn’t liking it. I didn’t realize that the Playboy thing was gonna be part of “The New Creatives.” That was cool, but then you look at your bank account and you’re like, Um….

CR: Did they pay you?

FW: No. None of that shit pays.You get the media attention but you’re not gonna make money. So, I learned a lot of lessons. Things they don’t teach in school. Why don’t they teach an economic empowerment class for artists?

Right now I’m paying attention to the Civil Rights people, the business people that came before us, and I think that artists have to be more political now. We kind of got screwed on the BeltLine situation because the artwork is what is bringing attention to these properties and areas. Real estate is making a killing because of the stuff that the artists are doing, yet we’re the last motherfuckers to receive benefits. I did the Pyramid on the BeltLine.

CR: Do you think it’s just over-gentrifying the city?

FW: The BeltLine is the railroad, from back when Atlanta first got rebuilt after the Civil War. There were all these business people that wanted to comfortably travel between Downtown and Inman Park. So they moved all the people of color out and put them in Reynoldstown, where now it’s happening again. But it is what it is. So with this whole BeltLine thing, it’s hard to get excited about it when you know what it’s doing. That’s also why I went over to the West End and started painting the pictures that I’ve been painting, which are primarily just people of color in heroic circumstances in beautiful poses. Because we need to see that, the kids of that neighborhood need to see it. My thing is that as a kid you should be able to walk out of your house and see pictures of people like you in an elevated state. You need something to aspire to.

CR: I totally agree and we were talking the other night about that area. There is a story to tell.

FW: Yeah, I’m very interested in changing the perception, not only of the people that live there but the people that come and visit. The bigger goal is to create art tourism based on all of the different types of creatives that live here, and really start to make our brand of art more recognizable on an international stage.

CR: Let’s rehash that a bit. You brought that up the other night and it intrigued me. Could you talk about the project you’re planning for next year?

FW: Bloom is the project and it is intended to transform Atlanta into an arts tourism destination. So you have people from places like Switzerland, Germany, France, any of the states in Africa, people who buy art, like in New York, would come to Atlanta to get Atlanta’s brand of art. To me, if we are doing it correctly, we would have this notion of soul, as in, We give a shit about stuff that’s going on and this is our response to it. This is a thing to think about. I feel like that is the kind of thing we should be doing since the Civil Rights Movement did originate here.

CR: So who do you see as our strong leaders today with that kind of influence?

FW: There are people that I see inching towards activism, but they are doing it more so from a business standpoint, which is sort of the modern version of it. Taj Anwar, Jay Z, Kevin Lee, and Jabari Graham. Those are guys that are putting their dollars behind things that they care about, and that helps. But on the level of what the Civil Rights leaders did, there’s no contemporary equivalent. There’s not a current machine like that. Black Lives Matter is not the same because they have not done a good job of listing out what they want. They are more like, “Shit’s fucked up, son! You know what I mean? Black Lives Matter!” But what can we do to equal it? We need laws, we need a shift in culture. Everything has to be shifted. There is a lot to do. My biggest way of moving things forward is to do what I’m doing and use the most of my ability, but I am also moving in political circles for some other things.

CR: Like what?

FW: Like an Art PAC. We have done a terrible job of organizing our power and our creatives, and when I say creatives, I mean designers, creative directors, people in the film industry.

CR: People that don’t have a union and don’t have a full time job?

FW: I wouldn’t say that as the film industry does have a union, but yes, for artists especially. I’m picking up where some art colleagues have dropped off. I wanted to start a PAC. I’ve already been talking with a lobbyist to get things in order. As soon as I figure out what the landscape will be, I’m going to start recruiting folks to get this thing rolling. We need a grown-up approach to this.

CR: It’s like getting a seat at the table. If that’s how laws are made and rules are made, then you need a seat at the table … So what else is happening with Bloom? Is it just you or are there more artists involved?

FW: I’m using a whole bunch of artists.

CR: Who you got so far?

FW: In mind, I have Peter Ferrari, Peter Frank, Fahamu Pecou and Steven Brandt. But I’m activating everybody. I do all this to transform the city, but the West End has to look a certain way, East Point and College Park has to look a certain way. Mainly because music has been talking about Atlanta for a while, but visually it hasn’t been activated. So what I want to do is activate that historical element in a contemporary way.

CR: Do you work with local rappers? Two of my current favorites are 2 Chainz and Migos?

FW: Yeah, I know some of them. I’ve had a long history of working with DJs and rap artists around here. I feel like the culture itself is not properly marketed in terms of tourism.

CR: I listen to Hip Hop Nation on satellite radio and they spend a lot of time talking about the A and pumping our local rap culture. Like Torae: The Tor Guide, one of the DJs, actually goes to rap shows here on a regular basis. And some of our local guys have really put us on the map. Why do you think we can’t get that same kind of thing done with visual art?

FW: Well, it is happening with visual art and that is my point, but we are just not capitalizing on it properly. We’re not doing a good job of displaying it. There are things that need to happen in terms of infrastructure, and I’m not trying to hit at the 2% sales tax nonsense, like, we’re bigger than that. They consistently don’t get it or don’t want to. They consistently don’t want to give us a cut. But either way, we’re coming for it.

CR: So have you made up with the City of Atlanta [over the public art ordinance]?

FW: I mean, we never had beef.

CR: You just didn’t like the prohibition on your work?

FW: Yeah, that’s over. But I’ve talked to just about all the people that needed to be talked to about it, except for the people that were responsible for it. I put out the word through the channels, but I haven’t heard anything back. And I’m really direct in terms of how I operate. I don’t have any negative intentions, I just want to see how we are going to make this city better. For everybody. Because if artists are creating these landscapes, we can’t be talking this 2% of this, 1% of that, tenths-of-a-penny-ass bullshit. You can’t do that anymore. We’ve grown beyond that. I look at what’s happening in Miami; we should be having massive art fairs in Atlanta. We would be the envy of the planet.

CR: Yeah, we don’t capitalize on that Southern vibe. Like Dallas and Houston do a really good job of tapping into the Texas vibe and people flock to it. Dallas has turned into one of the more significant art fairs, because people want to go there and get cowboy boots and drink margaritas.

FW: And they also make it a space for all the other leaders in tech and other industries to overlap. Nobody’s emerged with a vision like that here. Atlanta is a jewel and it needs to be shined up. It’s beyond time. That’s my mission.

CR: I wanted to touch on Colin Kaepernick and the mural you made of him in a Falcons uniform, since you got a lot of social media hits on that one. Is that the only one that you did? Did it start as a drawing?

FW: It started as a drawing and then I did the painting. I sat on it for awhile and then I was hyping myself up to do the mural, and I just kept telling my friends, “I’m gonna paint this mural of Kaepernick,” but a lot of them didn’t get it until they saw it. A lot of times I just need to build up the courage to do these because, you know, I don’t own these buildings. I just had one guy hit me up for the piece I just did of Martin Luther King and Ralph David Abernathy and Coretta Scott King in the West End. The guy who owns that spot now wants to do another piece. But I was a little worried about that shit coming back to get me. But what it does to the people who live there, those people like it a lot. A lot.

CR: I told you what Kwame Abernathy once said to me,“Why are all the BeltLine murals over on the East Side and the East Trail and over there in Old Fourth Ward? Why aren’t they over here?”

FW: That’s why I started doing them over there. And when the murals do come, they’re by white people. But that’s why I’m doing more of them on the West Side, because I’m not submitting my ideas to someone. I already know what it should look like.

CR: Who owns the building that you did the Kaepernick on?

FW: I don’t actually know, you know. It was just a good spot [chuckles].

CR: What street is that on?

FW: Fair Street and Joseph Lowery.

CR: How did you feel about the election? Did it charge you and your work? I mean, it’s a step back in my view, but some African-Americans are just like, “You know, I’ve been oppressed my entire life and this is just another motherfucker trying to take me down.”

FW: There’s that, but I’m not hopeless. Either you have to engage the machine or create a new one. I’m working the current system to help build the new system. It’s about the only thing you can do, next to just straight-up violence.

CR: Every time I want to get totally distraught, I remind myself that the same country that elected Trump also elected Obama.

FW: Yeah, and you know, the people you elect into office, you can’t just walk away. You have to make them do the things that they said they would, you know?

CR: Is there something that you’ve always wanted to say to the Atlanta art community that you’ve never had the chance to say?

FW: They should know how powerful they are. Consider it an ad agency of the people. You want equality, peace, opportunity? You have all these walls on which to stake that. Artists should make their space. Don’t be shy with that shit. Go for it. We now have the opportunity to paint walls without getting charged $1,500. But, while you’re doing that, consider who lives in that area. Artists really need to pay attention to that shit. Don’t be a tool for these real-estate developers. Be sensitive to the people that you’re speaking to with your work. If you’ve got a brand — because all these artists have brands now — make sure you’re speaking to them in a way that reflects them because that’s their community. I’m not going to go to Buford Highway and do some black shit. It’s Koreans and Mexicans over there. I’m gonna do something that reflects Koreans and Mexicans. You know what I’m saying? It’s just common sense.